Philosophical Work

Dualism

Descartes in his Passions of the Soul and The Description of the Human Body suggested that the body works like a machine, that it has material properties. The mind (or soul), on the other hand, was described as a nonmaterial and does not follow the laws of nature. Descartes argued that the mind interacts with the body at the pineal gland. This form of dualism or duality proposes that the mind controls the body, but that the body can also influence the otherwise rational mind, such as when people act out of passion. Most of the previous accounts of the relationship between mind and body had been uni-directional.

Descartes suggested that the pineal gland is “the seat of the soul” for several reasons. First, the soul is unitary, and unlike many areas of the brain the pineal gland appeared to be unitary (though subsequent microscopic inspection has revealed it is formed of two hemispheres). Second, Descartes observed that the pineal gland was located near the ventricles. He believed the cerebrospinal fluid of the ventricles acted through the nerves to control the body, and that the pineal gland influenced this process. Sensations delivered by the nerves to the pineal, he believed, caused it to vibrate in some sympathetic manner, which in turn gave rise to the emotions and caused the body to act. Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the mind-body problem for many years after Descartes’ death.

In present day discussions on the practice of animal vivisection, it is normal to consider Descartes as an advocate of this practice, as a result of his dualistic philosophy. Some of the sources say that Descartes denied the animals could feel pain, and therefore could be used without concern. Other sources consider that Descartes denied that animals had reason or intelligence, but did not lack sensations or perceptions, but these could be explained mechanistically.

Luc Paquin

A magic circle is circle (or sphere, field) of space marked out by practitioners of many branches of ritual magic, which they generally believe will contain energy and form a sacred space, or will provide them a form of magical protection, or both. It may be marked physically, drawn in salt or chalk, for example, or merely visualised. Its spiritual significance is similar to that of mandala and yantra in some Eastern religions.

Common Terms and Practices

A solomonic magic circle with a triangle of conjuration in the east. This would be drawn on the ground, and the operator would stand within the protection of the circle while a spirit was conjured into the triangle.

Traditionally, circles were believed by ritual magicians to form a protective barrier between themselves and what they summoned. In modern times, practitioners generally cast magic circles to contain and concentrate the energy they raise during a ritual.

Creating a magic circle is known as casting a circle, circle casting, and various other names.

Techniques

There are many published techniques for casting a circle, and many groups and individuals have their own unique methods. The common feature of these practices is that a boundary is traced around the working area. Some witchcraft traditions say that one must trace around the circle deosil three times. There is variation over which direction one should start in.

Circles may or may not be physically marked out on the ground, and a variety of elaborate patterns for circle markings can be found in grimoires and magical manuals, often involving angelic and divine names. Such markings, or a simple unadorned circle, may be drawn in chalk or salt, or indicated by other means such as with a cord.

The four cardinal directions are often prominently marked, such as with four candles. In ceremonial magic traditions the four directions are commonly related to the four archangels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael and Uriel (or Auriel), or the four classical elements, and also have four associated names of God. Other ceremonial traditions have candles between the quarters, i.e. in the north-east, north-west and so on. Often, an incantation will be recited stating the purpose and nature of the circle, often repeating an assortment of divine and angelic names.

In Wicca

In Wicca, a circle is typically nine feet in diameter, though the size can vary depending on the purpose of the circle, and the preference of the caster.

Some varieties of Wicca use the common ceremonial colour attributions for their “quarter candles”: yellow for Air in the east, red for Fire in the south, blue for Water in the west and green for Earth in the north (though these attributions differ according to geographical location and individual philosophy).

The common technique for raising energy within the circle is by means of a cone of power.

The barrier is believed to be fragile, so that leaving or passing through the circle would weaken or dispel it. This is referred to as “breaking the circle”. It is generally advised that practitioners do not leave the circle unless absolutely necessary.

In order to leave a circle and keep it intact, Wiccans believe a door must be cut in the energy of the circle, normally on the East side. Whatever was used to cast the circle is used to cut the doorway, such as a sword, staff or knife (athame), a doorway is “cut” in the circle, at which point anything may pass through without harming the circle. This opening must be closed afterwards by “reconnecting” the lines of the circle.

The circle is usually closed by the practitioner after they have finished by drawing in the energy with the athame or whatever was used to make the circle including their hand (usually in a widdershins: that is, counter-clockwise fashion). This is called closing the circle or releasing the circle. The term “opening” is often used, representing the idea the circle has been expanded and dissipated rather than closed in on itself.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Philosophical Work

Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences. For him the philosophy was a thinking system that embodied all knowledge, and expressed it in this way:

- Thus, all Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principals, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences, is the last degree of wisdom.

In his Discourse on the Method, he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as methodological skepticism: he rejects any ideas that can be doubted, and then reestablishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge.

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: thought exists. Thought cannot be separated from me, therefore, I exist (Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy). Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum (English: “I think, therefore I am”). Therefore, Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, therefore the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. “The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist.”

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines “thought” (cogitatio) as “what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it”. Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious.

To further demonstrate the limitations of these senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as the Wax Argument. He considers a piece of wax; his senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. When he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: it is still the same piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Therefore, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he should put aside the senses. He must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

- And so something that I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgment which is in my mind.

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and instead admitting only deduction as a method. In the third and fifth Meditation, he offers an ontological proof of a benevolent God (through both the ontological argument and trademark argument). Because God is benevolent, he can have some faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, he finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. In terms of epistemology therefore, he can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge. He, nevertheless, was very much aware that experimentation was necessary in order to verify and validate theories.

Descartes also wrote a response to External world scepticism. He argues that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, and are not willed by him. They are external to his senses, and according to Descartes, this is evidence of the existence of something outside of his mind, and thus, an external world. Descartes goes on to show that the things in the external world are material by arguing that God would not deceive him as to the ideas that are being transmitted, and that God has given him the “propensity” to believe that such ideas are caused by material things. He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams, and that one’s mind cannot have been “hijacked” by an evil demon placing an illusory external world before one’s senses.

Luc Paquin

Ski-Doo is a brand name of snowmobile manufactured by Bombardier Recreational Products. The first Ski-Doo was launched in 1959. It was a new invention of Joseph-Armand Bombardier. The original name was Ski-Dog, but a typographical error in a Bombardier brochure changed the name Ski-Dog to Ski-Doo.

The first Ski-Doos found customers with missionaries, trappers, and prospectors, land surveyors and other persons who need to travel in snowy remote areas. The largest success for the snowmobile came from sport enthusiasts, a market that opened the door to massive production of snowmobiles. This popularity led to skidoo (sometimes ski-doo), with the derived verb skidooing (or ski-dooing), becoming the traditional generic term for snowmobile in much of Canada.

Snowmobiles

Before the start of the company’s development of track vehicles, Joseph-Armand Bombardier experimented with propeller driven snow vehicles. His work with snowplane designs can be traced to before 1920. He quickly abandoned his efforts to develop a snowplane and turned his inventive skills to tracked vehicles.

From the start the company made truck-sized half-track vehicles, with skis in the front and Caterpillar tracks in the rear, designed for the worst winter conditions of the flatland Canadian countryside. After producing half-tracks in World War II for the Canadian Army the company experimented with new forms of track systems and developed an all-tracked heavy duty vehicle designed for logging and mining operations in extreme wilderness conditions, such as heavy snow or semi-liquid muskeg. They produced it under the name Muskeg tractor.

Each track is composed of 2 or more rubber belts that are joined into a loop. The loops are held together with interior wheel guides and exterior cleats, commonly called grousers. The tracks are driven by a large drive sprocket that engages the grousers in sequence and causes the track to rotate. 2 belt tracks were common on early model Bombardiers as well as for muskeg machines. For deep snow use, wider tracks, employing additional belts, are used for added flotation over the snow.

The research for the track base made it possible to produce a relatively small continuous rubber track for the light one or two person snowmobile the founder of the company had dreamed about during his teen years. This led to the invention of snowmobiles as we know them.

Development of the Small Snowmobile

The Ski-Doo was originally intended to be named the “Ski-Dog” because Bombardier meant it to be a practical vehicle to replace the dogsled for hunters and trappers. By accident, a printer misinterpreted the name and printed “Ski-Doo” in the first sales brochure. Public interest in the small snowmobiles grew quickly. Suddenly a new winter sport was born, centred in Quebec. In the first year, Bombardier sold 225 Ski-Doos; four years later, 8,210 were sold. But Armand was reluctant to focus too much on the Ski-Doo and move resources away from his all-terrain vehicles. He vividly remembered his earlier business setbacks that forced him to diversify. Armand slowed down promotion of the Ski-Doo line to prevent it from dominating the other company products but still dominate the entire snowmobile industry. The snowmobiles produced were of exceptional quality and performance, earning a better reputation than the rival Polaris and Arctic Cat brands of motosleds. In 1971, Bombardier completed the purchase of the Moto-Ski company to expand the Ski-Doo line and eliminate a competitor from the marketplace.

Tundra

I know the basics of the Tundra lineage, basically the Tundra was introduced in the 80’s with a 250 cc motor and came as a Tundra and Tundra LT, them the Tundra 2 came out (277cc).

- Weight: 370 lbs

- Ski stance: 32 inches

- Track specs: 139.5 x 15 x 3/4

- Engine: 277cc single, air cooled, belt less fan, oil injection

- Gas tank capacity: 6.9 US gal.

- Suspension: torque reaction, non articulating

- Carburetor: 34 mm VM round slide Mikuni

- Chain case gearing: 14:25

- Clutch primary: CVTech Power Block “Bomb Lite”

The Sass

The Model 1200 pump-action shotguns that are manufactured by the Winchester-Western Division of Olin Corporation. It was produced in 12-, 16- and 20-gauge. The military version of the 1200 has the ability to have a bayonet fixed on the end of the barrel to be used in close quarter combat. It is a takedown type shotgun which means it has the capability of being taken apart for easy transportation and storage.

History

The Winchester Model 1200 was introduced in 1964 as a low-cost replacement for the venerable Model 12. A small number of these weapons were acquired by the United States Army in 1968 and 1969. The military style Model 1200 was essentially the same weapon as the civilian version, except it had a ventilated handguard, sling swivels, and a bayonet lug.

Description

The Winchester Model 1200 came in barrel lengths of 30-inch, and 28-inch with a fixed choke or the Win-choke screw in choke tubes system and is a 12, 16, or 20-gauge, manually operated, slide action shotgun. The slide action, also known as a pump-action, means that the shotgun has a moving bolt system which is operated by a “wooden or composite slide called the fore-end”. The fore-end is located on the underside of the barrel and moves front to back. The weapon can hold a maximum of five rounds total with four in the tubular magazine and one in the chamber. It has a hammerless action which means that there is no external hammer spur. There is only a firing pin which strikes the primer on the shell to ignite the powder in the round. The Model 1200 is a takedown type of shotgun; it can be taken apart for easy storage and transportation.

The Model 1200 was the first shotgun to utilize a rotary bolt with four locking lugs secured within the barrel extension. The 1200 was Winchester’s first shotgun to incorporate the company’s patented Winchoke system, a quick change tube to allow the easy replacement of chokes.

Bayonet

A bayonet could be attached to the front end of the barrel of the Military version of the Model 1200. The primary uses of the bayonet on the model 1200 are for close combat, guarding prisoners, and riot duty. The most commonly used bayonet with the Model 1200 was the M1917 bayonet. After World War I ended, there was a large surplus of the M-1917 bayonets because the Army decided to keep the M1903 Springfield as the standard issued rifle. The M-1917 bayonet did not fit the Springfield rifles so instead of just getting rid of them, the Army decided to make newer shotguns compatible with the bayonets.

The Sass

Life

Sweden

Queen Christina of Sweden invited Descartes to her court in 1649 to organize a new scientific academy and tutor her in his ideas about love. She was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish the “Passions of the Soul”, a work based on his correspondence with Princess Elisabeth.

He was a guest at the house of Pierre Chanut, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Tre Kronor in Stockholm. There, Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian barometer, a tube with mercury. Challenging Blaise Pascal, Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure could be used in forecasting the weather.

Death

Descartes apparently started giving lessons to Queen Christina after her birthday, three times a week, at 5 a.m, in her cold and draughty castle. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his mechanical philosophy, he did not appreciate her interest in Ancient Greek. By 15 January 1650, Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February he caught a cold which quickly turned into a serious respiratory infection, and he died on 11 February. The cause of death was pneumonia according to Chanut, but peripneumonia according to the doctor Van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him. (The winter seems to have been mild, except for the second half of January) which was harsh as described by Descartes himself. “This remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes’ take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather.”

In 1996 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Johann van Wullen, who had been sent by Christina to treat him, something Descartes refused, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since. Descartes might have been assassinated as he asked for an emetic: wine mixed with tobacco.

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard used mainly for orphans in Adolf Fredriks kyrka in Stockholm. His manuscripts came into the possession of Claude Clerselier, Chanut’s brother-in-law, and “a devout Catholic who has begun the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding and publishing his letters selectively.” In 1663, the Pope placed his works on the Index of Prohibited Books. In 1666 his remains were taken to France and buried in the Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. In 1671 Louis XIV prohibited all the lectures in Cartesianism. Although the National Convention in 1792 had planned to transfer his remains to the Panthéon, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819, missing a finger and the skull.

Luc Paquin

Ronnie Branigan

Volunteer, Introductory Program

When Ronnie Branigan retired in 1993, she knew immediately that she wanted to become a part of the Aphasia Institute. “I wanted to give my time to something meaningful and I knew that I could make a difference at the Aphasia Institute.”

Ronnie’s certainty came from her brief interaction with the Aphasia Institute more than 30 years ago when her husband had a stroke in his 40’s. It was then that Ronnie first learned about the Aphasia Institute.

Today, Ronnie is one of the longest-serving members of the volunteer team. She volunteers two days every week, working with the Introductory Program and in our Conversation Program. She says her greatest joy is being able to witness the change that happens through the Introductory Program. “At first, people are shy and withdrawn but by the third or fourth week, you see the group coming together to support each other, and you see confidence building in each member as they learn new skills.”

Providing support to spouses is particularly fulfilling for her. “Often this is the first time that they have the opportunity to meet others in the same situation. They can say whatever they want without fear of judgment and they can hear from others who have had similar experiences. Having lived it first-hand, I can appreciate what they go through.”

Anna Taylor

Volunteer, Introductory Program and Community Aphasia Program

Anna Taylor saw a sign that caught her eye at the grocery store one day: Aphasia Centre. When she got home, she looked up the word “aphasia” in the dictionary never having heard of it before. Two days later, the universe seemed to speak to her again when she came across a recruitment ad in the paper for volunteers at the Aphasia Centre. That was 17 years ago, and Anna is one of Aphasia Institute’s longest serving volunteers.

“I get enormous pleasure from the work I do. I think there are very few things more rewarding than seeing somebody who really has not had what I call a proper conversation,” says Anna.

In the Introductory Program, she primarily works with clients who have very little verbal output, and who arrive apprehensive. “They might be thinking – ‘do they know I can’t speak’ , ‘do they understand how difficult this is for me?’, ” says Anna. “However all of that changes after just a few weeks as confidence grows and members begin to open up and express their opinion, share their joys and their sorrows in a new community that offers hope for the future.”

Norma

Life

France

In 1620 Descartes left the army. He visited Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto, then visited various countries before returning to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris. It was there that he composed his first essay on method: Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property to invest in bonds, which provided a comfortable income for the rest of his life. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627. In the fall of the same year, in the residence of the papal nuncio Guidi di Bagno, where he came with Mersenne and many other scholars to listen to a lecture given by the alchemist Monsieur de Chandoux on the principles of a supposed new philosophy. Cardinal Bérulle urged him to write an exposition of his own new philosophy.

Netherlands

Descartes returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628. In April 1629 he joined the University of Franeker, studying under Metius, living either with a Catholic family, or renting the Sjaerdemaslot, where he invited in vain a French cook and an optician. The next year, under the name “Poitevin”, he enrolled at the Leiden University to study mathematics with Jacob Golius, who confronted him with Pappus’s hexagon theorem, and astronomy with Martin Hortensius. In October 1630 he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, who was born in 1635 in Deventer, at which time Descartes taught at the Utrecht University. Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes was not devoid of passions but rather defended them; he wept upon her death in 1640. “Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man.” Russell Shorto postulated that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes’ work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.

Despite frequent moves he wrote all his major work during his 20+ years in the Netherlands, where he managed to revolutionize mathematics and philosophy. In 1633, Galileo was condemned by the Catholic Church, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish Treatise on the World, his work of the previous four years. Nevertheless, in 1637 he published part of this work in three essays: Les Météores (The Meteors), La Dioptrique (Dioptrics) and La Géométrie (Geometry), preceded by an introduction, his famous Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method), also meant for women. In it Descartes lays out four rules of thought, meant to ensure that our knowledge rests upon a firm foundation.

The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641 he published a metaphysics work, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed, in 1644, by Principia Philosophiæ (Principles of Philosophy), a kind of synthesis of the Meditations and the Discourse. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a long correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, devoted mainly to moral and psychological subjects. Connected with this correspondence, in 1649 he published Les Passions de l’âme (Passions of the Soul), that he dedicated to the Princess. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the Louis XIV, though it was never paid.

A French translation of Principia Philosophiæ, prepared by Abbot Claude Picot, was published in 1647. This edition Descartes dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. In the preface Descartes praised true philosophy as a means to attain wisdom. He identifies four ordinary sources to reach wisdom, and finally says that there is a fifth, better and more secure, consisting in the search for first causes.

Luc Paquin

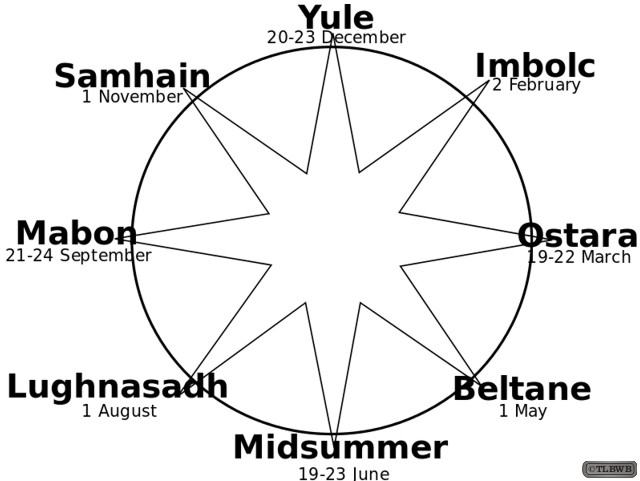

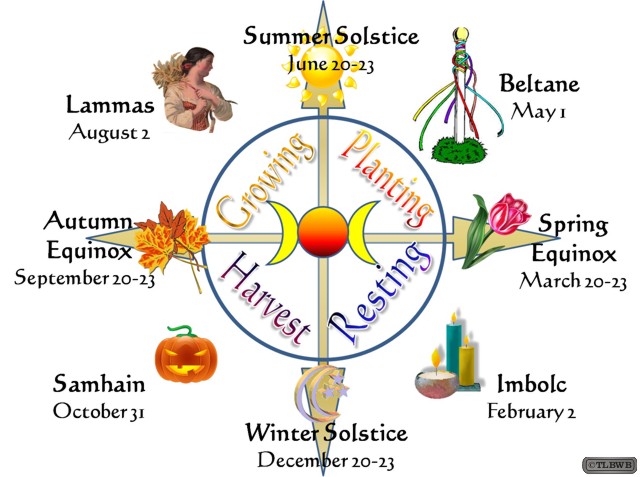

The Wheel of the Year is an annual cycle of seasonal festivals, observed by many modern Pagans. It consists of either four or eight festivals: either the solstices and equinoxes, known as the “quarter days”, or the four midpoints between, known as the “cross quarter days”; syncretic traditions like Wicca often celebrate all eight festivals.

The festivals celebrated by differing sects of modern Paganism can vary considerably in name and date. Observing the cycle of the seasons has been important to many people, both ancient and modern, and many contemporary Pagan festivals are based to varying degrees on folk traditions.

Among Wiccans, the festivals are also referred to as sabbats, with Gerald Gardner claiming this term was passed down from the Middle Ages, when the terminology for Jewish Shabbats was commingled with that of other heretical celebrations.

Origins

The contemporary Wheel of the Year is somewhat of a modern innovation. Many historical pagan traditions celebrated various equinoxes, solstices, and the days approximately midway between them (termed cross-quarter days) for their seasonal and agricultural significances. But none were known to have held all eight above all other annual, sacred times. The modern understanding of the Wheel is a result of the cross-cultural awareness that began developing by the time of Modern Europe.

Mid-20th century British Paganism had a strong influence on early adoption of an eightfold Wheel. By the late 1950s, the Wiccan Bricket Wood Coven and Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids had both adopted eightfold ritual calendars, for balance and more frequent celebrations. This also had the benefit of more closely aligning celebration between the two influential Pagan orders.

Due to early Wicca’s influence on Paganism and their syncretic adoption of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic motifs, the most commonly used English festival names for the Wheel of the Year tend to be Celtic and Germanic.

The American Ásatrú movement has adopted, over time, a calendar in which the Heathen major holidays figure alongside many Days of Remembrance which celebrate heroes of the Edda and the Sagas, figures of Germanic history, and the Viking Leif Ericson, who explored and settled Vinland (North America). These festivals are not, however, as evenly distributed throughout the year as in Wicca and other Heathen denominations.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Life

Early Life

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine (now Descartes), Indre-et-Loire, France, on March 31, 1596. When he was one year old, his mother Jeanne Brochard died after trying to give birth to another child that also died. His father Joachim was a member of the Parlement of Brittany at Rennes. René lived with his grandmother and with his great-uncle. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots. In 1607, late because of his fragile health, he entered the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche where he was introduced to mathematics and physics, including Galileo’s work. After graduation in 1614, he studied two years at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and Licence in law, in accordance with his father’s wishes that he should become a lawyer. From there he moved to Paris.

In his book, Discourse On The Method, he says “I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way so as to derive some profit from it.”

Given his ambition to become a professional military officer, in 1618, Descartes joined the Dutch States Army in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau, and undertook a formal study of military engineering, as established by Simon Stevin. Descartes therefore received much encouragement in Breda to advance his knowledge of mathematics. In this way he became acquainted with Isaac Beeckman, principal of a Dordrecht school, for whom he wrote the Compendium of Music (written 1618, published 1650). Together they worked on free fall, catenary, conic section and Fluid statics. Both believed that it was necessary to create a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics. While in the service of the Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, Descartes visited the labs of Tycho Brahe in Prague and Johannes Kepler in Regensburg.

Visions

According to Adrien Baillet, on the night of 10-11 November 1619 (St. Martin’s Day), while stationed in Neuburg an der Donau, Descartes shut himself in a room with an “oven” (probably a Kachelofen or masonry heater) to escape the cold. While within, he had three visions and believed that a divine spirit revealed to him a new philosophy. Upon exiting he had formulated analytical geometry and the idea of applying the mathematical method to philosophy. He concluded from these visions that the pursuit of science would prove to be, for him, the pursuit of true wisdom and a central part of his life’s work. Descartes also saw very clearly that all truths were linked with one another, so that finding a fundamental truth and proceeding with logic would open the way to all science. This basic truth, Descartes found quite soon: his famous “I think therefore I am”.

Luc Paquin