LostBeardedWhite

Abrahamic Religions

New Testament

The New Testament condemns the practice as an abomination, just as the Old Testament had (Galatians 5:20, compared with Revelation 21:8; 22:15; and Acts 8:9; 13:6), though the overall topic of Biblical law in Christianity is still disputed. The word in most New Testament translations is “sorcerer”/”sorcery” rather than “witch”/”witchcraft”.

Judaism

Jewish law views the practice of witchcraft as being laden with idolatry and/or necromancy; both being serious theological and practical offenses in Judaism. Although Maimonides vigorously denied the efficacy of all methods of witchcraft, and claimed that the Biblical prohibitions regarding it were precisely to wean the Israelites from practices related to idolatry, according to Traditional Judaism, it is acknowledged that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods. Rabbis of the Talmud also condemned magic when it produced something other than illusion, giving the example of two men who use magic to pick cucumbers (Sanhedrin 67a). The one who creates the illusion of picking cucumbers should not be condemned, only the one who actually picks the cucumbers through magic. However, some of the Rabbis practiced “magic” themselves or taught the subject. For instance, Rabbah created a person and sent him to Rabbi Zera, and Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Oshaya studied every Friday together and created a small calf to eat on Shabbat (Sanhedrin 67b). In these cases, the “magic” was seen more as divine miracles (i.e., coming from God rather than “unclean” forces) than as witchcraft.

Judaism does make it clear that Jews shall not try to learn about the ways of witches (Deuteronomy/Devarim 18: 9-10) and that witches are to be put to death. (Exodus/Shemot 22:17)

Judaism’s most famous reference to a medium is undoubtedly the Witch of Endor whom Saul consults, as recounted in the First Book of Samuel, chapter 28.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Abrahamic Religions

The belief in sorcery and its practice seem to have been widespread in the Ancient Near East. It played a conspicuous role in the cultures of ancient Egypt and in Babylonia, with the latter composing an Akkadian anti-witchcraft ritual, the Maqlû. A section from the Code of Hammurabi (about 2000 B.C.) prescribes:

- If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him.

Hebrew Bible

According to the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia:

- In the Holy Scripture references to sorcery are frequent, and the strong condemnations of such practices found there do not seem to be based so much upon the supposition of fraud as upon the abomination of the magic in itself.

The King James Bible uses the words “witch”, “witchcraft”, and “witchcrafts” to translate the Masoretic kashaph or kesheph and qesem; these same English terms are used to translate pharmakeia in the Greek New Testament text. Verses such as Deuteronomy 18:11-12 and Exodus 22:18 (“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”) thus provided scriptural justification for Christian witch hunters in the early Modern Age.

The precise meaning of the Hebrew kashaph, usually translated as “witch” or “sorceress”, is uncertain. In the Septuagint, it was translated as pharmakeia or pharmakous. In the 16th century, Reginald Scot, a prominent critic of the witch-trials, translated kashaph, pharmakeia, and their Latin Vulgate equivalent veneficos as all meaning “poisoner”, and on this basis, claimed that “witch” was an incorrect translation and poisoners were intended. His theory still holds some currency, but is not widely accepted, and in Daniel 2:2 kashaph is listed alongside other magic practitioners who could interpret dreams: magicians, astrologers, and Chaldeans. Suggested derivations of Kashaph include mutterer (from a single root) or herb user (as a compound word formed from the roots kash, meaning “herb”, and hapaleh, meaning “using”). The Greek pharmakeia literally means “herbalist” or one who uses or administers drugs, but it was used virtually synonymously with mageia and goeteia as a term for a sorcerer.

The Bible provides some evidence that these commandments against sorcery were enforced under the Hebrew kings:

- And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and he went, and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night: and he said, I pray thee, divine unto me by the familiar spirit, and bring me him up, whom I shall name unto thee. And the woman said unto him, Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land: wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?

Note that the Hebrew word ob, translated as familiar spirit in the above quotation, has a different meaning than the usual English sense of the phrase; namely, it refers to a spirit that the woman is familiar with, rather than to a spirit that physically manifests itself in the shape of an animal.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Contemporary Witchcraft Contrasted With Satanism

Satanism is a broad term referring to diverse beliefs that share a symbolic association with, or admiration for, Satan, who is seen as a liberating figure. While it is heir to the same historical period and pre-Enlightenment beliefs that gave rise to modern witchcraft, it is generally seen as completely separate from modern witchcraft and Wicca, and has little or no connection to them.

Modern witchcraft considers Satanism to be the “dark side of Christianity” rather than a branch of Wicca: – the character of Satan referenced in Satanism exists only in the theology of the three Abrahamic religions, and Satanism arose as, and occupies the role of, a rebellious counterpart to Christianity, in which all is permitted and the self is central. (Christianity can be characterized as having the diametrically opposite views to these.) Such beliefs become more visibly expressed in Europe after the Enlightenment, when works such as Milton’s Paradise Lost were described anew by romantics who suggested that they presented the biblical Satan as an allegory representing crisis of faith, individualism, free will, wisdom and enlightenment; a few works from that time also begin to directly present Satan in a less negative light, such as Letters from the Earth. The two major trends are theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism; the former venerates Satan as a supernatural patriarchal deity, while the latter views Satan as merely a symbolic embodiment of certain human traits.

Organized groups began to emerge in the mid 20th century, including the Ophite Cultus Satanas (1948) and The Church of Satan (1966). It was estimated that there were up to 100,000 Satanists worldwide by 2006, twice the number estimated in 1990. Satanistic beliefs have been largely permitted as a valid expression of religious belief in the West. For example, they were allowed in the British Royal Navy in 2004, and an appeal was considered in 2005 for religious status as a right of prisoners by the Supreme Court of the United States. Contemporary Satanism is mainly an American phenomenon, although it began to reach Eastern Europe in the 1990s around the time of the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Contemporary Witchcraft

Modern practices identified by their practitioners as “witchcraft” have grown dramatically since the early 20th century. Generally portrayed as revivals of pre-Christian European ritual and spirituality, they are understood to involve varying degrees of magic, shamanism, folk medicine, spiritual healing, calling on elementals and spirits, veneration of ancient deities and archetypes, and attunement with the forces of nature.

The first Neopagan groups to publicly appear, during the 1950s and 60s, were Gerald Gardner’s Bricket Wood coven and Roy Bowers’ Clan of Tubal Cain. They operated as initiatory secret societies. Other individual practitioners and writers such as Paul Huson also claimed inheritance to surviving traditions of witchcraft.

Wicca

During the 20th century, interest in witchcraft in English-speaking and European countries began to increase, inspired particularly by Margaret Murray’s theory of a pan-European witch-cult originally published in 1921, since discredited by further careful historical research. Interest was intensified, however, by Gerald Gardner’s claim in 1954 in Witchcraft Today that a form of witchcraft still existed in England. The truth of Gardner’s claim is now disputed too, with different historians offering evidence for or against the religion’s existence prior to Gardner.

The Wicca that Gardner initially taught was a witchcraft religion having a lot in common with Margaret Murray’s hypothetically posited cult of the 1920s. Indeed, Murray wrote an introduction to Gardner’s Witchcraft Today, in effect putting her stamp of approval on it. Wicca is now practised as a religion of an initiatory secret society nature with positive ethical principles, organised into autonomous covens and led by a High Priesthood. There is also a large “Eclectic Wiccan” movement of individuals and groups who share key Wiccan beliefs but have no initiatory connection or affiliation with traditional Wicca. Wiccan writings and ritual show borrowings from a number of sources including 19th and 20th-century ceremonial magic, the medieval grimoire known as the Key of Solomon, Aleister Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis and pre-Christian religions. Both men and women are equally termed “witches.” They practice a form of duotheistic universalism.

Since Gardner’s death in 1964, the Wicca that he claimed he was initiated into has attracted many initiates, becoming the largest of the various witchcraft traditions in the Western world, and has influenced other Neopagan and occult movements.

Stregheria

Stregheria is an Italian witchcraft religion popularised in the 1980s by Raven Grimassi, who claims that it evolved within the ancient Etruscan religion of Italian peasants who worked under the Catholic upper classes.

Modern Stregheria closely resembles Charles Leland’s controversial late-19th-century account of a surviving Italian religion of witchcraft, worshipping the Goddess Diana, her brother Dianus/Lucifer, and their daughter Aradia. Leland’s witches do not see Lucifer as the evil Satan that Christians see, but a benevolent god of the Sun and Moon.

The ritual format of contemporary Stregheria is roughly similar to that of other Neopagan witchcraft religions such as Wicca. The pentagram is the most common symbol of religious identity. Most followers celebrate a series of eight festivals equivalent to the Wiccan Wheel of the Year, though others follow the ancient Roman festivals. An emphasis is placed on ancestor worship.

Feri Tradition

The Feri Tradition is a modern traditional witchcraft practice founded by Victor Henry Anderson and his wife Cora. It is an ecstatic tradition which places strong emphasis on sensual experience and awareness, including sexual mysticism, which is not limited to heterosexual expression.

Most practitioners worship three main deities; the Star Goddess, and two divine twins, one of whom is the blue God. They believe that there are three parts to the human soul, a belief taken from the Hawaiian religion of Huna as described by Max Freedom Long.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Good and Evil

Accusations of Witchcraft

Éva Pócs states that reasons for accusations of witchcraft fall into four general categories:

- A person was caught in the act of positive or negative sorcery

- A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients’ or the authorities’ trust

- A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbours

- A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or Occultism

She identifies three varieties of witch in popular belief:

- The “neighbourhood witch” or “social witch”: a witch who curses a neighbour following some conflict.

- The “magical” or “sorcerer” witch: either a professional healer, sorcerer, seer or midwife, or a person who has through magic increased her fortune to the perceived detriment of a neighbouring household; due to neighbourly or community rivalries and the ambiguity between positive and negative magic, such individuals can become labelled as witches.

- The “supernatural” or “night” witch: portrayed in court narratives as a demon appearing in visions and dreams.

“Neighbourhood witches” are the product of neighbourhood tensions, and are found only in self-sufficient serf village communities where the inhabitants largely rely on each other. Such accusations follow the breaking of some social norm, such as the failure to return a borrowed item, and any person part of the normal social exchange could potentially fall under suspicion. Claims of “sorcerer” witches and “supernatural” witches could arise out of social tensions, but not exclusively; the supernatural witch in particular often had nothing to do with communal conflict, but expressed tensions between the human and supernatural worlds; and in Eastern and Southeastern Europe such supernatural witches became an ideology explaining calamities that befell entire communities.

Violence Related to Accusations

Belief in witchcraft continues to be present today in some societies and accusations of witchcraft are the trigger of serious forms of violence, including murder. Such incidents are common in places such as Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal and Tanzania. Accusations of witchcraft are sometimes linked to personal disputes, jealousy, and conflicts between neighbors or family over land or inheritance. Witchcraft related violence is often discussed as a serious issue in the broader context of violence against women.

In Tanzania, about 500 older women are murdered each year following accusations against them of witchcraft. Apart from extrajudicial violence, there is also state-sanctioned violence in some jurisdictions. For instance, in Saudi Arabia practicing ‘witchcraft and sorcery’ is a crime punishable by death and the country has executed people for this crime in 2011, 2012 and 2014.

Children in some regions of the world, such as parts of Africa, are also vulnerable to violence related to witchcraft accusations. Such incidents have also occurred in immigrant communities in the UK, including the much publicized case of the murder of Victoria Climbié.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Good and Evil

Demonology

In Christianity and Islam, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and apostasy and to be viewed as evil. Among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Late Medieval/Early Modern period, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch, and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchchraft, culminating in the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena. Throughout this time, it was increasingly believed that Christianity was engaged in an apocalyptic battle against the Devil and his secret army of witches, who had entered into a diabolical pact. In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men. “Warlock” is sometimes mistakenly used for male witch. Accusations of witchcraft were often combined with other charges of heresy against such groups as the Cathars and Waldensians.

The Malleus Maleficarum, (Latin for “Hammer of The Witches) was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on the work, and was later officially condemned by the Catholic Church in 1490.

In the modern Western world, witchcraft accusations have often accompanied the satanic ritual abuse moral panic. Such accusations are a counterpart to blood libel of various kinds, which may be found throughout history across the globe.

White Witches

Throughout the early modern period, the English term “witch” was not exclusively negative in meaning, and could also indicate cunning folk. “There were a number of interchangeable terms for these practitioners, ‘white’, ‘good’, or ‘unbinding’ witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers, however ‘cunning-man’ and ‘wise-man’ were the most frequent.” The contemporary Reginald Scot noted, “At this day it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, ‘she is a witch’ or ‘she is a wise woman'”. Folk magicians throughout Europe were often viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing, which could lead to their being accused as “witches” in the negative sense. Many English “witches” convicted of consorting with demons seem to have been cunning folk whose fairy familiars had been demonised; many French devins-guerisseurs (“diviner-healers”) were accused of witchcraft, and over one half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers.

Some of the healers and diviners historically accused of witchcraft have considered themselves mediators between the mundane and spiritual worlds, roughly equivalent to shamans. Such people described their contacts with fairies, spirits often involving out-of-body experiences and travelling through the realms of an “other-world”. Beliefs of this nature are implied in the folklore of much of Europe, and were explicitly described by accused witches in central and southern Europe. Repeated themes include participation in processions of the dead or large feasts, often presided over by a horned male deity or a female divinity who teaches magic and gives prophecies; and participation in battles against evil spirits, “vampires”, or “witches” to win fertility and prosperity for the community.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Etymology and Definitions

The word “witchcraft” derives from the Old English wiccecræft, a compound of “wicce” (“witch”) and “cræft” (“craft”).

In anthropological terminology, a “witch” differs from a sorcerer in that they do not use physical tools or actions to curse; their maleficium is perceived as extending from some intangible inner quality, and the person may be unaware that they are a “witch”, or may have been convinced of their own nature by the suggestion of others. This definition was pioneered in a study of central African magical beliefs by E. E. Evans-Pritchard, who cautioned that it might not correspond with normal English usage.

Historians of European witchcraft have found the anthropological definition difficult to apply to European and British witchcraft, where “witches” could equally use (or be accused of using) physical techniques, as well as some who really had attempted to cause harm by thought alone. European witchcraft is seen by historians and anthropologists as an ideology for explaining misfortune; however, this ideology has manifested in diverse ways, as described below.

Overview

Alleged Practices

Historically the witchcraft label has been applied to practices people believe influence the mind, body, or property of others against their will – or practices that the person doing the labeling believes undermine social or religious order. Some modern commentators believe the malefic nature of witchcraft is a Christian projection. The concept of a magic-worker influencing another person’s body or property against their will was clearly present in many cultures, as traditions in both folk magic and religious magic have the purpose of countering malicious magic or identifying malicious magic users. Many examples appear in ancient texts, such as those from Egypt and Babylonia. Malicious magic users can become a credible cause for disease, sickness in animals, bad luck, sudden death, impotence and other such misfortunes. Witchcraft of a more benign and socially acceptable sort may then be employed to turn the malevolence aside, or identify the supposed evil-doer so that punishment may be carried out. The folk magic used to identify or protect against malicious magic users is often indistinguishable from that used by the witches themselves.

There has also existed in popular belief the concept of white witches and white witchcraft, which is strictly benevolent. Many neopagan witches strongly identify with this concept, and profess ethical codes that prevent them from performing magic on a person without their request.

Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, such practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people – even if the orthodox establishment opposes it.

Spell Casting

Probably the most obvious characteristic of a witch was the ability to cast a spell, “spell” being the word used to signify the means employed to carry out a magical action. A spell could consist of a set of words, a formula or verse, or a ritual action, or any combination of these. Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of runes or sigils on an object to give it magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet) of a person to affect him or her magically; by the recitation of incantations; by the performance of physical rituals; by the employment of magical herbs as amulets or potions; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying) for purposes of divination; and by many other means.

Necromancy (Conjuring the Dead)

Strictly speaking, “necromancy” is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy – although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical Witch of Endor performed it (1 Sam. 28), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham:

- Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arise from death.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Witchcraft (also called witchery or spellcraft) broadly means the practice of, and belief in, magical skills and abilities that are able to be exercised individually, by designated social groups, or by persons with the necessary esoteric secret knowledge. Witchcraft is a complex concept that varies culturally and societally, therefore it is difficult to define with precision and cross-cultural assumptions about the meaning or significance of the term should be applied with caution. Witchcraft often occupies a religious, divinatory, or medicinal role, and is often present within societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view. Although witchcraft can often share common ground with related concepts such as sorcery, the paranormal, magic, superstition, necromancy, possession, shamanism, healing, spiritualism, nature worship, and the occult, it is usually seen as distinct from these when examined by sociologists and anthropologists.

Concept

The concept of witchcraft and the belief in its existence have existed throughout recorded history. They have been present or central at various times, and in many diverse forms, among cultures and religions worldwide, including both “primitive” and “highly advanced” cultures, and continue to have an important role in many cultures today. Scientifically, the existence of magical powers and witchcraft are generally believed to lack credence and to be unsupported by high quality experimental testing, although individual witchcraft practices and effects may be open to scientific explanation or explained via mentalism and psychology.

Historically, the predominant concept of witchcraft in the Western world derives from Old Testament laws against witchcraft, and entered the mainstream when belief in witchcraft gained Church approval in the Early Modern Period. It posits a theosophical conflict between good and evil, where witchcraft was generally evil and often associated with the Devil and Devil worship. This culminated in deaths, torture and scapegoating (casting blame for human misfortune), and many years of large scale witch-trials and witch hunts, especially in Protestant Europe, before largely ceasing during the European Age of Enlightenment. Christian views in the modern day are diverse and cover the gamut of views from intense belief and opposition (especially from Christian fundamentalists) to non-belief, and in some churches even approval. From the mid-20th century, witchcraft – sometimes called contemporary witchcraft to clearly distinguish it from older beliefs – became the name of a branch of modern paganism. It is most notably practiced in the Wiccan and modern witchcraft traditions, and no longer practices in secrecy.

The Western mainstream Christian view is far from the only societal perspective about witchcraft. Many cultures worldwide continue to have widespread practices and cultural beliefs that are loosely translated into English as “witchcraft”, although the English translation masks a very great diversity in their forms, magical beliefs, practices, and place in their societies. During the Age of Colonialism, many cultures across the globe were exposed to the modern Western world via colonialism, usually accompanied and often preceded by intensive Christian missionary activity. Beliefs related to witchcraft and magic in these cultures were at times influenced by the prevailing Western concepts. Witch hunts, scapegoating, and killing or shunning of suspected witches still occurs in the modern era, with killings both of victims for their supposedly magical body parts, and of suspected witchcraft practitioners.

Suspicion of modern medicine due to beliefs about illness being due to witchcraft also continues in many countries to this day, with tragic healthcare consequences. HIV/AIDS and Ebola virus disease are two examples of often-lethal infectious disease epidemics whose medical care and containment has been severely hampered by regional beliefs in witchcraft. Other severe medical conditions whose treatment is hampered in this way include tuberculosis, leprosy, epilepsy and the common severe bacterial Buruli ulcer. Public healthcare often requires considerable education work related to epidemology and modern health knowledge in many parts of the world where belief in witchcraft prevails, to encourage effective preventive health measures and treatments, to reduce victim blaming, shunning and stigmatization, and to prevent the killing of people and endangering of animal species for body parts believed to convey magical abilities.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

A magic circle is circle (or sphere, field) of space marked out by practitioners of many branches of ritual magic, which they generally believe will contain energy and form a sacred space, or will provide them a form of magical protection, or both. It may be marked physically, drawn in salt or chalk, for example, or merely visualised. Its spiritual significance is similar to that of mandala and yantra in some Eastern religions.

Common Terms and Practices

A solomonic magic circle with a triangle of conjuration in the east. This would be drawn on the ground, and the operator would stand within the protection of the circle while a spirit was conjured into the triangle.

Traditionally, circles were believed by ritual magicians to form a protective barrier between themselves and what they summoned. In modern times, practitioners generally cast magic circles to contain and concentrate the energy they raise during a ritual.

Creating a magic circle is known as casting a circle, circle casting, and various other names.

Techniques

There are many published techniques for casting a circle, and many groups and individuals have their own unique methods. The common feature of these practices is that a boundary is traced around the working area. Some witchcraft traditions say that one must trace around the circle deosil three times. There is variation over which direction one should start in.

Circles may or may not be physically marked out on the ground, and a variety of elaborate patterns for circle markings can be found in grimoires and magical manuals, often involving angelic and divine names. Such markings, or a simple unadorned circle, may be drawn in chalk or salt, or indicated by other means such as with a cord.

The four cardinal directions are often prominently marked, such as with four candles. In ceremonial magic traditions the four directions are commonly related to the four archangels Michael, Gabriel, Raphael and Uriel (or Auriel), or the four classical elements, and also have four associated names of God. Other ceremonial traditions have candles between the quarters, i.e. in the north-east, north-west and so on. Often, an incantation will be recited stating the purpose and nature of the circle, often repeating an assortment of divine and angelic names.

In Wicca

In Wicca, a circle is typically nine feet in diameter, though the size can vary depending on the purpose of the circle, and the preference of the caster.

Some varieties of Wicca use the common ceremonial colour attributions for their “quarter candles”: yellow for Air in the east, red for Fire in the south, blue for Water in the west and green for Earth in the north (though these attributions differ according to geographical location and individual philosophy).

The common technique for raising energy within the circle is by means of a cone of power.

The barrier is believed to be fragile, so that leaving or passing through the circle would weaken or dispel it. This is referred to as “breaking the circle”. It is generally advised that practitioners do not leave the circle unless absolutely necessary.

In order to leave a circle and keep it intact, Wiccans believe a door must be cut in the energy of the circle, normally on the East side. Whatever was used to cast the circle is used to cut the doorway, such as a sword, staff or knife (athame), a doorway is “cut” in the circle, at which point anything may pass through without harming the circle. This opening must be closed afterwards by “reconnecting” the lines of the circle.

The circle is usually closed by the practitioner after they have finished by drawing in the energy with the athame or whatever was used to make the circle including their hand (usually in a widdershins: that is, counter-clockwise fashion). This is called closing the circle or releasing the circle. The term “opening” is often used, representing the idea the circle has been expanded and dissipated rather than closed in on itself.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

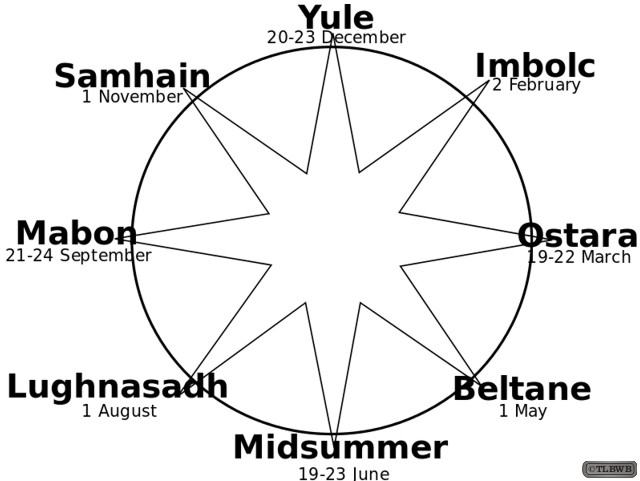

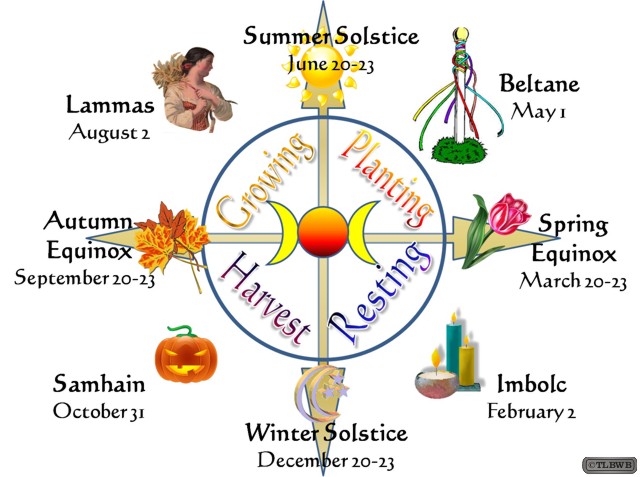

The Wheel of the Year is an annual cycle of seasonal festivals, observed by many modern Pagans. It consists of either four or eight festivals: either the solstices and equinoxes, known as the “quarter days”, or the four midpoints between, known as the “cross quarter days”; syncretic traditions like Wicca often celebrate all eight festivals.

The festivals celebrated by differing sects of modern Paganism can vary considerably in name and date. Observing the cycle of the seasons has been important to many people, both ancient and modern, and many contemporary Pagan festivals are based to varying degrees on folk traditions.

Among Wiccans, the festivals are also referred to as sabbats, with Gerald Gardner claiming this term was passed down from the Middle Ages, when the terminology for Jewish Shabbats was commingled with that of other heretical celebrations.

Origins

The contemporary Wheel of the Year is somewhat of a modern innovation. Many historical pagan traditions celebrated various equinoxes, solstices, and the days approximately midway between them (termed cross-quarter days) for their seasonal and agricultural significances. But none were known to have held all eight above all other annual, sacred times. The modern understanding of the Wheel is a result of the cross-cultural awareness that began developing by the time of Modern Europe.

Mid-20th century British Paganism had a strong influence on early adoption of an eightfold Wheel. By the late 1950s, the Wiccan Bricket Wood Coven and Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids had both adopted eightfold ritual calendars, for balance and more frequent celebrations. This also had the benefit of more closely aligning celebration between the two influential Pagan orders.

Due to early Wicca’s influence on Paganism and their syncretic adoption of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic motifs, the most commonly used English festival names for the Wheel of the Year tend to be Celtic and Germanic.

The American Ásatrú movement has adopted, over time, a calendar in which the Heathen major holidays figure alongside many Days of Remembrance which celebrate heroes of the Edda and the Sagas, figures of Germanic history, and the Viking Leif Ericson, who explored and settled Vinland (North America). These festivals are not, however, as evenly distributed throughout the year as in Wicca and other Heathen denominations.

The Lost Bearded White Brother