Norma Paquin

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys.

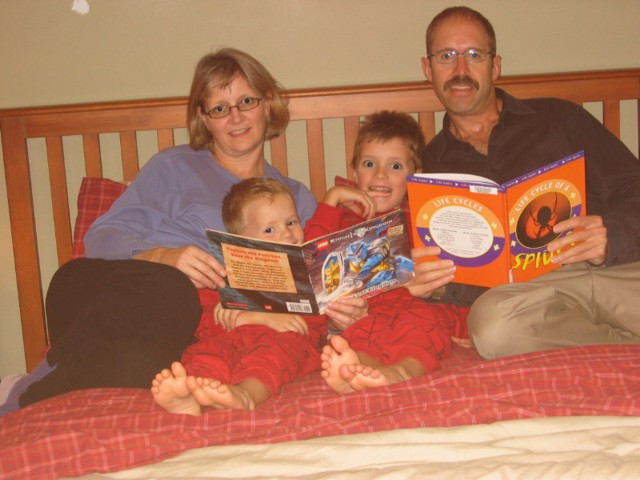

The Ardiel family piles into their big bed for a favourite nightly ritual. Jane reads a storybook aloud to her boys and husband while running her index finger along the page under the words so six-year old Ben can follow along. Sometimes Ben reads a page. Aiden, at four-years old is too young to read so he snuggles in to enjoy the tale. For dad Scott, although reading a sentence aloud is a struggle, he participates as fully as he can in this bonding family routine.

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys. “[Aphasia] , that’s been a struggle from the beginning. [I] can’t tell [the boys how to do things], but I have to show them,” says Scott.

Even though Scott knows what he wants to say, he has difficulty expressing it. Sometimes he finds it hard to understand what others are saying and reading can be difficult. Scott and Jane found the Aphasia Institute to be a “nugget of hope” once Scott was released from rehab after his stroke. They found comfort in an environment that understood the impact aphasia had on the whole family.

Jane joined the Family Support and Education Group and found a community that empathized with her experience.

Today Scott is a member of the Toastmaster Aphasia Gavel Club and an active volunteer at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. Jane has made it her mission to educate every medical professional they have encountered along this journey about aphasia.

“Much of my own healing through this experience has come from the opportunity to help others. There’s a saying – we achieve happiness when we seek the happiness and wellbeing of others,” says Jane.

Jane & Scott Ardiel

Norma

When people lose their ability to communicate due to brain damage caused by stroke or trauma, as persons with aphasia do, there is a good news and a bad news. The good news is that often not all is lost. Depending on the extensiveness of the damage, parts of the brain that used to be involved in speaking or understanding language may still be functioning. Speech therapies aim to induce these preserved areas to reorganize and regain their ability to produce and process speech. The not so good news is that such reorganization takes a long time, especially in older individuals.

Many people are familiar with traditional speech therapies that employ exercises to help persons with aphasia re-learn how to use language to communicate with their families and friends. Depending on the size and the location of brain damage, speech therapies can take years and improvement is usually slow. However, scientists are now looking into a newer type of treatment that combines traditional speech therapy with a weak electrical stimulation of the brain that might speed up recovery from aphasia. The method is called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and is applied non-invasively, by placing an electrode on top of the skull.

When people hear about electrical stimulation used to treat brain disorders, many conjure up an image from the 1975 movie “One flew over the cuckoo’s nest” which featured scenes of painful electroconvulsive therapy. This type of intervention, which in reality is painless, is still applied as a last resort to alleviate treatment-resistent depression and involves much stronger electrical currents than tDCS, which uses electrical current equivalent roughly to a 9V battery. The PBS Newshour video below describes the principles behind tDCS and how it could be applied for purposes like focusing the mind and keeping it alert.

The idea behind using tDCS in Aphasia therapy is that the small amount of current applied to the brain may enhance plasticity and prime the brain to learn faster. The approach would be to employ tDCS in combination with traditional clinical therapies rather than as a substitution.

There are many parts of the brain that are involved in understanding or producing speech and those parts are intricately connected into complex networks. Information flows between the various parts of the speech and language networks along cables called axons. Such information flow is important for the brain to access vocabulary and grammar rules, assemble words into sentences and send commands to the mouth and the tongue to produce speech. When stroke or trauma damages the areas that are part of this language network, the information flow is disturbed or cut off and people experience communication deficits. New connections need to be established between the preserved brain areas in order to regain one’s ability to speak.

The weak electrical currents of tDCS might stimulate the brain to form these new connections faster than it would with traditional speech therapy alone. But how exactly that would happen and what biological changes in the brain accompany the behavioral modulations observed in the video above is still unclear.

At present, tDCS as applied to aphasia is still considered experimental treatment and health insurance would not cover the cost of therapy. Data on tDCS efficacy for treating aphasia are still scarce. Most studies are conducted with small number of patients, limited language tasks, and short follow-up periods. However, at least some of the studies seem to suggest that tDCS has potential to improve aphasia rehabilitation.

Multiple centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe are in the process of conducting more rigorous clinical trials and may have more evidence soon whether tDCS works for aphasia. Those interested in enrolling in such studies can go to ClinicalTrials.gov to find out more information.

As methods improve and more data become available, tDCS may prove to be a great tool that will boost recovery from aphasia, which for the moment is still a long and arduous journey.

Norma

Sacks on TED

Oliver Sacks

Norma

About Oliver Sacks

Biography

Oliver Sacks, MD, FRCP

Oliver Sacks was born in 1933 in London, England into a family of physicians and scientists (his mother was a surgeon and his father a general practitioner). He earned his medical degree at Oxford University (Queen’s College), and did residencies and fellowship work at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco and at UCLA. Since 1965, he has lived in New York, where he is a practicing neurologist.

From 2007 to 2012, he served as a Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, and he was also designated the university’s first Columbia University Artist. Dr. Sacks is currently a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine, where he practices as part of the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center. He is also a visiting professor at the University of Warwick.

In 1966 Dr. Sacks began working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, a chronic care hospital where he encountered an extraordinary group of patients, many of whom had spent decades in strange, frozen states, like human statues, unable to initiate movement. He recognized these patients as survivors of the great pandemic of sleepy sickness that had swept the world from 1916 to 1927, and treated them with a then-experimental drug, L-dopa, which enabled them to come back to life. They became the subjects of his bookAwakenings, which later inspired a play by Harold Pinter (“A Kind of Alaska”) and the Oscar-nominated feature film (“Awakenings”) with Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Sacks is perhaps best known for his collections of case histories from the far borderlands of neurological experience, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and An Anthropologist on Mars, in which he describes patients struggling to live with conditions ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism, parkinsonism, musical hallucination, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, retardation, and Alzheimer’s disease.

He has investigated the world of Deaf people and sign language in Seeing Voices, and a rare community of colorblind people in The Island of the Colorblind. He has written about his experiences as a doctor in Migraine and as a patient in A Leg to Stand On. His autobiographicalUncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood was published in 2001, and his most recent books are Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (2007), The Mind’s Eye (2010), and Hallucinations (2012).

Sacks’s work, which has been supported by the Guggenheim Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, regularly appears in the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, as well as various medical journals. The New York Times has referred to Dr. Sacks as “the poet laureate of medicine”, and in 2002 he was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize by Rockefeller University, which recognizes the scientist as poet. He is an honorary fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and holds honorary degrees from many universities, including Oxford, the Karolinska Institute, Georgetown, Bard, Gallaudet, Tufts, and the Catholic University of Peru.

Oliver Sacks

Norma

About Oliver Sacks

Oliver Sacks, M.D. is a physician, a best-selling author, and a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine. The New York Times has referred to him as “the poet laureate of medicine”.

He is best known for his collections of neurological case histories, including The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain and An Anthropologist on Mars. Awakenings, his book about a group of patients who had survived the great encephalitis lethargica epidemic of the early twentieth century, inspired the 1990 Academy Award-nominated feature film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Dr. Sacks is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books.

Oliver Sacks

Norma

Dr. Oliver Sacks wrote and told many stories over the years about his patients’ struggles with disease and their feats in the face of extraordinary challenge. In one of them, he narrates how he used to greet aphasia patients by singing “Happy Birthday” to them, irrespective of whether it was their birthday or not. He did this because everyone knew the words of this song, and often even people who had lost their ability to speak could sing along parts of it. It was his kind way of letting a person with aphasia join in.

Today is the 82nd birthday of Dr. Sacks – a luminous mind, a celebrated writer, and a treasured board member of the National Aphasia Association. As many of you may have already heard, Dr. Sacks recently shared with the public that he has terminal cancer. The news has saddened many hearts, including ours here at the NAA. But today, on this special birthday, we wanted to celebrate with Dr. Sacks the years he has spent bringing to us the magic of science and medicine through his fascinating writing and language. And we wanted to thank him for his extraordinary kindness towards persons with aphasia. We have selected a few excerpts and videos where Dr. Sacks talks about Aphasia and his personal encounters with people who suffer from this devastating communication deficit.

Maybe the best place to start is an excerpt from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, one of the most beloved books from Oliver Sacks, a collection of clinical tales about patients with neurological disorders. The book includes accounts about aphasia as well. One of those tales relates the story of patients with the severest receptive or global aphasia who had gathered to watch the President speaking. It begins like this:

- What was going on? A roar of laughter from the aphasia ward, just as the President’s speech was coming on, and they had all been so eager to hear the President speaking…

Dr. Sacks has had many encouraging words for people with aphasia, even those who have had the hardest of luck.

- I think that even in the most severely affected patients, something can be done. If not by way of recovering their language, by way of making life more tolerable and more fun.

In a 2009 interview with Harper’s Magazine about his book Musicophilia, Dr. Sacks answers questions about music therapy, among other things. He shares his experience with an aphasia patient for whom this type of therapy proved life changing.

- One sixty-seven-year-old man, aphasic for eighteen months – he could only produce meaningless grunts and had received three months of speech therapy without effect – started to produce words two days after beginning melodic intonation therapy; in two weeks, he had an effective vocabulary of a hundred words, and at six weeks, he could carry on “short, meaningful conversation”s.

In this video Oliver Sacks talks about a patient, a woman called Patricia, who had had a stroke that resulted in aphasia. Dr. Sacks recounts how her extraordinary will and ability to find a way around her communication deficits has inspired him to write about her.

Besides being touching stories about patients, these accounts also show the interest Dr. Sacks took in his patients, their problems, and the way disease affected their lives.

Happy Birthday, Dr. Sacks!

Norma

Hodor might have aphasia but persons with aphasia are not “simple-minded”.

It is all over the news – Hodor has been diagnosed with expressive aphasia. If you belong to what seems to be a minority of people who don’t watch HBO’s Game of Thrones then you probably haven’t heard of Hodor, so here is how The Conversation describes him:

- Hodor is the brawny, simple-minded stableboy of the Stark family in Winterfell. His defining characteristic, of course, is that he only speaks a single word: “Hodor”.

No matter what the situation is, what is asked of him, or what is being said to him, it’s always – hodor, hodor, hodor. Which is how he got his aphasia diagnosis:

- Those who read the A Song of Ice and Fire book series by George R R Martin may know something that the TV fans don’t: his name isn’t actually Hodor. According to his great-grandmother Old Nan, his real name is Walder. “No one knew where ‘Hodor’ had come from,” she says, “but when he started saying it, they started calling him by it. It was the only word he had.”

- Whether he intended it or not, Martin created a character who is a textbook example of someone with a neurological condition called expressive aphasia.

Diagnosing with aphasia a popular character from a widely watched TV show (its 5th season premiere drew 8 million viewers) makes for a fun read and it is also a great way to spread awareness about this neurological disorder. Most people have never heard of aphasia despite that it is a fairly common condition that affects about a third of all stroke patients. Aphasia results from brain injury that damages areas that control speech and language. Such damage is most commonly caused by stroke or head trauma but it could also result from tissue degeneration.

Media attention that boosts aphasia awareness is welcome but there is a caveat. Many of the articles that diagnosed Hodor’s language peculiarity as aphasia introduced him as “simple-minded”. Other online depictions of Hodor also characterize him as “slow of wits”. This kind of allusions leave the impression that Hodor has intellectual deficits.

The articles about Hodor make for a fun and fascinating read about aphasia and the history of its discovery. But given the context, it would have been great if they emphasized that aphasia is a disorder that affects speech and language only. It does not affect people’s intellectual capabilities.

Inability to express oneself, speaking with grammatically incorrect sentences, inserting words that make no logical sense, and difficulty understanding what is being said are all characteristics of various forms of aphasia. Unfortunately, they are also associated with intellectual deficits. This is a problem with which many persons with aphasia struggle because people who are unfamiliar with the disorder assume that patients with aphasia have intellectual deficits as well. Which is why it is important to make the distinction clear.

Norma

Many people are not familiar with aphasia or they might just not realize that someone has difficulty communicating because of aphasia.

Carrying an Aphasia ID is a great way to ease communication awkwardness. You can customize and print an ID card for free by following the link provided below. You can then present the card when buying groceries, paying for gas, meeting new people, or in any other situation when you think a person might need to be informed that you have aphasia.

Click on the link aphasia ID card to customize and print your own card for free.

A free online tool for people with aphasia.

Create a personalized Aphasia ID that you can print and start carrying right away. This is a great way to ease communication awkwardness, especially for people who are unfamiliar with aphasia.

Aphasia ID. Create a customized ID right at home.

- Luc

- Paquin

- Professional

- Date Issued: 8/2/2015

Make yours today!

I am a: Professional

Carry your ID to help people know about your challenges with communication. You can also make IDs for your friends who don’t have aphasia, so they can show their support.

Norma

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

What is Aphasia?

Aphasia is a neurological disorder caused by damage to the portions of the brain that are responsible for language. Primary signs of the disorder include difficulty in expressing oneself when speaking, trouble understanding speech, and difficulty with reading and writing. Aphasia is not a disease, but a symptom of brain damage. Most commonly seen in adults who have suffered a stroke, aphasia can also result from a brain tumor, infection, head injury, or dementia that damages the brain. It is estimated that about 1 million people in the United States today suffer from aphasia. The type and severity of language dysfunction depends on the precise location and extent of the damaged brain tissue.

Generally, aphasia can be divided into four broad categories:

- (1) Expressive aphasia involves difficulty in conveying thoughts through speech or writing. The patient knows what he wants to say, but cannot find the words he needs.

- (2) Receptive aphasia involves difficulty understanding spoken or written language. The patient hears the voice or sees the print but cannot make sense of the words.

- (3) Patients with anomic or amnesia aphasia, the least severe form of aphasia, have difficulty in using the correct names for particular objects, people, places, or events.

- (4) Global aphasia results from severe and extensive damage to the language areas of the brain. Patients lose almost all language function, both comprehension and expression. They cannot speak or understand speech, nor can they read or write.

Is there any treatment?

In some instances, an individual will completely recover from aphasia without treatment. In most cases, however, language therapy should begin as soon as possible and be tailored to the individual needs of the patient. Rehabilitation with a speech pathologist involves extensive exercises in which patients read, write, follow directions, and repeat what they hear. Computer-aided therapy may supplement standard language therapy.

What is the prognosis?

The outcome of aphasia is difficult to predict given the wide range of variability of the condition. Generally, people who are younger or have less extensive brain damage fare better. The location of the injury is also important and is another clue to prognosis. In general, patients tend to recover skills in language comprehension more completely than those skills involving expression.

What research is being done?

The NINDS and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders conduct and support a broad range of scientific investigations to increase our understanding of aphasia, find better treatments, and discover improved methods to restore lost function to people who have aphasia.

Norma

Coping and support

People with aphasia

If you have aphasia, the following tips may help you communicate with others:

- Carry a card explaining that you have aphasia and what aphasia is.

- Carry identification and information on how to contact significant others.

- Carry a pencil and a small pad of paper with you at all times.

- Use drawings, diagrams or photos as shortcuts.

- Use gestures or point to objects.

Family and friends

Family members and friends can use the following tips when communicating with a person with aphasia:

- Simplify your sentences and slow your pace.

- Keep conversations one-on-one initially.

- Allow the person time to talk.

- Don’t finish sentences or correct errors.

- Reduce distracting noise in the environment.

- Keep paper and pencils or pens available.

- Write a key word or a short sentence to help explain something.

- Help the person with aphasia create a book of words, pictures and photos to assist with conversations.

- Use drawings or gestures when you aren’t understood.

- Involve the person with aphasia in conversations as much as possible.

- Check for comprehension or summarize what you’ve discussed.

Support groups

Local chapters of such organizations as the National Aphasia Association, the American Stroke Association, the American Heart Association and some medical centers may offer support groups for people with aphasia and others affected by the disorder. These groups provide people with a sense of community, a place to air frustrations and learn coping strategies. Ask your doctor or speech-language pathologist if he or she knows of any local support groups.

Norma