Friend

Friend

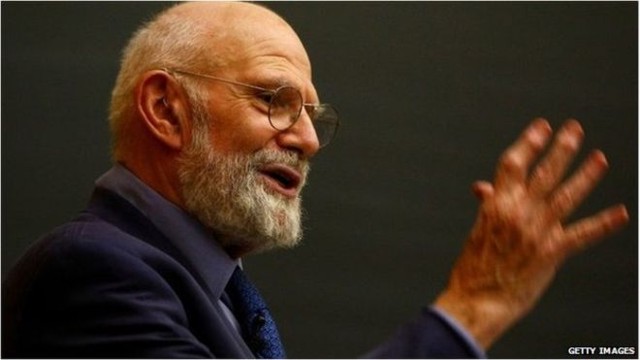

British neurologist Oliver Sacks has died at the age of 82, it has been confirmed.

The acclaimed author, whose book Awakenings inspired an Oscar nominated film of the same name, reportedly died of cancer at his home in New York.

In February he wrote about his illness – and being “face to face with dying”.

His publicist Jacqui Graham paid tribute to Dr Sacks, saying he was “unlike anybody I have ever met”, while JK Rowling said he was “inspirational”.

Dr Sacks was best known for his writing, including his book Awakenings – his account of how he brought a group of patients “back to life” after they spent years in “frozen states” after an illness.

The film version, which starred Robert De Niro and Robin Williams, was nominated for three Academy Awards in 1991, including best picture.

Dr Sacks, who was born in London but had lived in New York since 1965, was also the author of several other books about unusual medical conditions, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat and The Island Of The Colorblind.

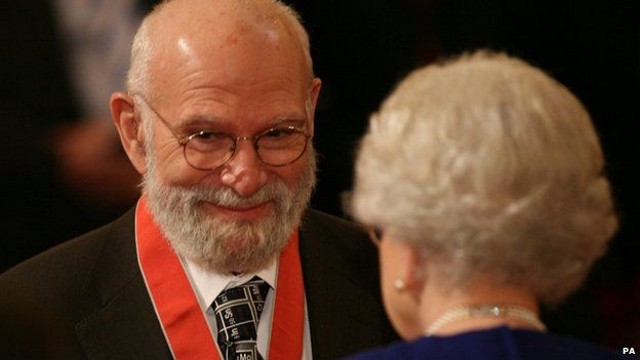

He was awarded several honorary degrees recognising his contribution to science and literature, as well as a CBE in 2008 in the Queen’s Birthday Honours.

Mrs Graham told the BBC Dr Sacks was “unlike anybody else I’ve ever met”.

She said she received an email from his long-time PA saying the neurologist had “a very good death, in the same way that he’d had a very good life”.

Mrs Graham said: “He died surrounded by the things he loved and the people he loved, very peacefully, after an illness he had known about since January this year. He taught us a great deal, right up until the very end.

“He always taught us what it was to be human, and he taught us what it is to die.”

‘Humane, inspirational’

Paying tribute to Dr Sacks, she added: “To say he was unique is for once in the world true.

“He was completely himself – eccentric, but in a marvellous way. He was just completely full of love for life and very impish, and he was childish in the very best sense.”

Other tributes to the author have been paid on Twitter, including by the author JK Rowling, who called him “great, humane and inspirational”.

Biologist Richard Dawkins tweeted: “I met Oliver Sacks only twice, but greatly admired him. Sad to hear of his death.”

Dr Sacks earned a medical degree at Queen’s College, Oxford University, and later began working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital, in the Bronx, New York, in 1966.

While there he encountered patients who had spent decades in frozen states, unable to initiate movement.

He recognised the patients as survivors of a pandemic of sleepy sickness that had swept the world from 1916 to 1927, and treated them with a then-experimental drug, L-dopa, which enabled them to regain consciousness.

They became the subjects of Awakenings and also later inspired a play by Harold Pinter – A Kind of Alaska.

In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and An Anthropologist on Mars he described patients struggling to live with conditions ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s.

He also investigated the world of deaf people and sign language in Seeing Voices, and a rare community of colour-blind people in The Island of the Colorblind.

More recently, he served as a professor of neurology and psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Centre from 2007 to 2012.

He was also a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine.

Norma

Sam was an athletic 18-year old living in Kenya when he sustained a serious brain injury during a sporting accident.

Sam was an athletic 18-year old living in Kenya when he sustained a serious brain injury during a sporting accident. The injury resulted in aphasia and with little support in Kenya, Sam’s mother was desperate for help. She was frustrated that people saw her son as “stupid” and was deeply concerned as her son became increasingly depressed and hopeless about his future.

She contacted the Aphasia Institute and because of our international training program, we were able to connect Sam and his mother with a Speech-Language Pathologist in South Africa who had been trained in our methods. Sam is now beginning to see hope on the horizon.

Sam and his mother

Norma

René Descartes (31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist who spent most of his life in the Dutch Republic.

He has been dubbed the father of modern philosophy, and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day. In particular, his Meditations on First Philosophy continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes’s influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system – allowing reference to a point in space as a set of numbers, and allowing algebraic equations to be expressed as geometric shapes in a two- or three-dimensional coordinate system (and conversely, shapes to be described as equations) – was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the scientific revolution and has been described as an example of genius.

Descartes refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers, and refused to trust his own senses. He frequently set his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, a treatise on the early modern version of what are now commonly called emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic “as if no one had written on these matters before”. Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differs from the schools on two major points: First, he rejects the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejects any appeal to final ends – divine or natural – in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God’s act of creation.

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza and Descartes were all well versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

His best known philosophical statement is “Cogito ergo sum” (French: Je pense, donc je suis; I think, therefore I am), found in part IV of Discourse on the Method (1637 – written in French but with inclusion of “Cogito ergo sum”) and §7 of part I of Principles of Philosophy (1644 – written in Latin).

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

“Martial Morality”

Traditional Chinese schools of martial arts, such as the famed Shaolin monks, often dealt with the study of martial arts not just as a means of self-defense or mental training, but as a system of ethics. Wude can be translated as “martial morality” and is constructed from the words wu, which means martial, and de, which means morality. Wude deals with two aspects; “morality of deed” and “morality of mind”. Morality of deed concerns social relations; morality of mind is meant to cultivate the inner harmony between the emotional mind (Xin) and the wisdom mind (Hui). The ultimate goal is reaching “no extremity” (Wuji) – closely related to the Taoist concept of wu wei – where both wisdom and emotions are in harmony with each other.

Virtues:

Deed

- Humility: Qian

- Virtue: Cheng

- Respect: Li

- Morality: Yi

- Trust: Xin

Mind

- Courage: Yong

- Patience: Ren

- Endurance: Heng

- Perseverance: Yi

- Will: Zhi

Luc Paquin

Aurora was a family physician with a busy practice when she suffered a massive stroke in 2006. “This place (Aphasia Institute) has given us hope and a support system”.

Aurora was a family physician with a busy practice when she suffered a massive stroke in 2006. Hoping that the Aphasia Institute might be able to help his wife, her husband Buddy brought an unresponsive Aurora to the Institute’s Introductory Program. Aurora sat slumped in her wheelchair, barely looking at her communication partner throughout the first session but over the course of the program, glimmers of hope began to emerge. Volunteers and staff were able to engage Aurora and prompt her to look up when in conversation – she even started initiating chats.

Through supportive Institute programs, Aurora and Buddy worked together to develop new skills and today Aurora continues to thrive, communicating her thoughts and asserting her desires and wants at home. Although their lives have been forever changed, “this place (Aphasia Institute) has given us hope and a support system,” says Buddy.

Aurora and Buddy

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Wushu

The word wu is translated as ‘martial’ in English, however in terms of etymology, this word has a slightly different meaning. In Chinese, wu is made of two parts; the first meaning “stop” (zhi) and the second meaning “invaders lance” (je). This implies that “wu’” is a defensive use of combat. The term “wushu” meaning “martial arts” goes back as far as the Liang Dynasty (502-557) in an anthology compiled by Xiao Tong, (Prince Zhaoming; d. 531), called Selected Literature (Wenxian). The term is found in the second verse of a poem by Yan Yanzhi titled: “Huang Taizi Shidian Hui Zuoshi”.

- “The great man grows the many myriad things . . .

Breaking away from the military arts,

He promotes fully the cultural mandates.”

(Translation from: Echoes of the Past by Yan Yanzhi (384-456))

The term wushu is also found in a poem by Cheng Shao (1626-1644) from the Ming Dynasty.

The earliest term for ‘martial arts’ can be found in the Han History (206BC-23AD) was “military fighting techniques” (bing jiqiao). During the Song period (c.960) the name changed to “martial arts” (wuyi). In 1928 the name was changed to “national arts” (guoshu) when the National Martial Arts Academy was established in Nanjing. The term reverted to wushu under the People’s Republic of China during the early 1950s.

As forms have grown in complexity and quantity over the years, and many forms alone could be practiced for a lifetime, modern styles of Chinese martial arts have developed that concentrate solely on forms, and do not practice application at all. These styles are primarily aimed at exhibition and competition, and often include more acrobatic jumps and movements added for enhanced visual effect compared to the traditional styles. Those who generally prefer to practice traditional styles, focused less on exhibition, are often referred to as traditionalists. Some traditionalists consider the competition forms of today’s Chinese martial arts as too commercialized and losing much of its original values.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Controversy

Even though forms in Chinese martial arts are intended to depict realistic martial techniques, the movements are not always identical to how techniques would be applied in combat. Many forms have been elaborated upon, on the one hand to provide better combat preparedness, and on the other hand to look more aesthetically pleasing. One manifestation of this tendency toward elaboration beyond combat application is the use of lower stances and higher, stretching kicks. These two maneuvers are unrealistic in combat and are used in forms for exercise purposes. Many modern schools have replaced practical defense or offense movements with acrobatic feats that are more spectacular to watch, thereby gaining favor during exhibitions and competitions. This has led to criticisms by traditionalists of the endorsement of the more acrobatic, show-oriented Wushu competition. Even though appearance has always been important in many traditional forms as well, all patterns exist for their combat functionality. Historically forms were often performed for entertainment purposes long before the advent of modern Wushu as practitioners have looked for supplementary income by performing on the streets or in theaters. As documented in ancient literature during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) suggest some sets, (including two + person sets: dui da also called dui lian) became very elaborate and ‘flowery’, many mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire category of martial arts known as Hua Fa Wuyi. During the Northern Song period, it was noted by historians this type of training had a negative influence on training in the military.

Many traditional Chinese martial artists, as well as practitioners of modern sport combat, have become critical of the perception that forms work is more relevant to the art than sparring and drill application, while most continue to see traditional forms practice within the traditional context – as vital to both proper combat execution, the Shaolin aesthetic as art form, as well as upholding the meditative function of the physical art form.

Another reason why techniques often appear different in forms when contrasted with sparring application is thought by some to come from the concealment of the actual functions of the techniques from outsiders.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

Traditional “sparring” sets, called dui da or dui lian, were an important part of Chinese martial arts for centuries. Dui lian literally means, to train by a pair of combatants opposing each other – the character lian, means to practice; to train; to perfect one’s skill; to drill. As well, often one of these terms are also included in the name of fighting sets (shuang yan), “paired practice” (zheng sheng), “to struggle with strength for victory” (di), match – the character suggests to strike an enemy; and “to break” (po).

Generally there are 21, 18, 12, 9 or 5 drills or ‘exchanges/groupings’ of attacks and counterattacks, in each dui lian set. These drills were considered only generic patterns and never meant to be considered inflexible ‘tricks’. Students practiced smaller parts/exchanges, individually with opponents switching sides in a continuous flow. Basically, dui lian were not only a sophisticated and effective methods of passing on the fighting knowledge of the older generation, they were important and effective training methods. The relationship between single sets and contact sets is complicated, in that some skills cannot be developed with single sets, and, conversely, with dui lian. Unfortunately, it appears that most traditional combat oriented dui lian and their training methodology have disappeared, especially those concerning weapons. There are a number of reasons for this. In modern Chinese martial arts most of the dui lian are recent inventions designed for light props resembling weapons, with safety and drama in mind. The role of this kind of training has degenerated to the point of being useless in a practical sense, and, at best, is just performance.

By the early Song period, sets were not so much “individual isolated technique strung together” but rather were composed of techniques and counter technique groupings. It is quite clear that “sets” and “fighting (2 person) sets” have been instrumental in TCM for many hundreds of years – even before the Song Dynasty. There are images of two person weapon training in Chinese stone painting going back at least to the Eastern Han Dynasty.

According to what has been passed on by the older generations, the approximate ratio of contact sets to single sets was approximately 1:3. In other words, about 30% of the sets practiced at Shaolin were contact sets, dui lian, and two person drill training. This is, in part, evidenced by the Qing Dynasty mural at Shaolin.

Ancient literature from the Tang and Northern Song Dynasties suggests that some sets, including those that required two or more participants, became very elaborate and mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire new category of martial arts known as “fancy patterns for developing military skill” (Hua Fa Wuyi). During the Northern Song period it was noted by historians that this phenomenon had a negative influence on training in the military.

For most of its history, Shaolin martial arts was largely weapon-focused: staves were used to defend the monastery, not bare hands. Even the more recent military exploits of Shaolin during the Ming and Qing Dynasties involved weapons. According to some traditions, monks first studied basics for one year and were then taught staff fighting so that they could protect the monastery. Although wrestling has been as sport in China for centuries, weapons have been the most important part of Chinese wushu since ancient times. If one wants to talk about recent or ‘modern’ developments in Chinese martial arts (including Shaolin for that matter), it is the over-emphasis on bare hand fighting. During the Northern Song Dynasty (976-997 A.D) when platform fighting known as Da Laitai (Title Fights Challenge on Platform) first appeared, these fights were with only swords and staves. Although later, when bare hand fights appeared as well, it was the weapons events that became the most famous. These open-ring competitions had regulations and were organized by government organizations; some were also organized by the public. The government competitions resulted in appointments to military posts for winners and were held in the capital as well as in the prefectures.

Luc Paquin

In 2006, Dr. Donald Meeks was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

Dr. Donald Meeks dedicated his life to helping people with addictions, building a distinguished reputation as a Professor at the University of Toronto and the Associate Director of the Clinical Institute at the Centre for Mental Health and Addiction (CAMH). His work took him around the world as a special consultant to the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

In 2006, he was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

After the second stroke, Don was left with lingering weakness on his right side, permanent damage to his memory, and aphasia.

For an academic man who had built his career on his ability to read, write and express himself verbally, aphasia was an unexpected blow. “I suffered the most from a lack of self confidence in pubic situations – I feared that I would be inarticulate or lose my train of thought,” says Don. “Being referred to the Aphasia Institute was a ‘stroke of luck’!”

Don and his wife Sherril entered the Aphaisa Institute’s Introductory Program with great hope… and the program delivered. Don’s confidence began to build and Sherril connected with fellow caregivers and built a network of support for herself. Together, they learned about aphasia and some of the supportive communication techniques.

Don quickly graduated to the Aphasia Institute’s Toastmasters Club, where he continues today. Sherril remains connected to the Family group. Both are looking ahead with optimism although they appreciate that the journey has been very different for each of them.

Looking back, there’s an irony to having spent decades helping others only to find themselves, as Don refers to it, ‘on the other side of the gurney’.

Both know that the Aphasia Institute will be a key part of their lives for some time to come. “This is a best practice demonstration of everything I taught for years,” says Don. “The community at AI is astounding – we feel so welcomed and very much a part of this wonderful, wonderful community.”

Dr. Donald Meeks

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms or taolu (Pinyin: tàolù) in Chinese are series of predetermined movements combined so they can be practiced as a continuous set of movements. Forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a particular style branch, and were often taught to advanced students selected for that purpose. Forms contained both literal, representative and exercise-oriented forms of applicable techniques that students could extract, test, and train in through sparring sessions.

Today, many consider forms to be one of the most important practices in Chinese martial arts. Traditionally, they played a smaller role in training for combat application, and took a back seat to sparring, drilling and conditioning. Forms gradually build up a practitioner’s flexibility, internal and external strength, speed and stamina, and they teach balance and coordination. Many styles contain forms that use weapons of various lengths and types, using one or two hands. Some styles focus on a certain type of weapon. Forms are meant to be both practical, usable, and applicable as well as to promote fluid motion, meditation, flexibility, balance, and coordination. Teachers are often heard to say “train your form as if you were sparring and spar as if it were a form.”

There are two general types of forms in Chinese martial arts. Most common are solo forms performed by a single student. There are also sparring forms – choreographed fighting sets performed by two or more people. Sparring forms were designed both to acquaint beginning fighters with basic measures and concepts of combat, and to serve as performance pieces for the school. Weapons-based sparring forms are especially useful for teaching students the extension, range, and technique required to manage a weapon.

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

The term taolu is a shorten version of Tao Lu Yun Dong, an expression introduced only recently with the popularity of modern wushu. This expression refers to “exercise sets” and is used in the context of athletics or sport.

In contrast, in traditional Chinese martial arts alternative terminologies for the training of “sets or forms” are:

- Lian Quan Tao – Practicing sequence of fist

- Lian Quan Jiao – Practicing fists and feet

- Lian Bing Qi – Practicing weapons

- Dui Da and Dui Lian – Fighting sets

Luc Paquin