Aphasia

Aphasia

Some people with aphasia have difficulty processing the written words that they see.

It is possible for a person with aphasia to look at one word, for example, “fork”, and think of a spoon or something else related to “fork”. Another kind of problem is to look at a written word and fail to recognize it in any meaningful way. For example, a person with aphasia could look at a written word like “fork” and not be able to think what it means. In these cases, it is helpful to add additional written information, gesture, or pictures, to help reading comprehension. Compare the following two statements: “Get the spoon” and “Get the spoon – the one for soup”. In the second statement there is additional information that may help trigger the correct meaning of the target, “spoon”. Even though the second statement is longer, it provides redundancy which helps comprehension.

Some people with aphasia have trouble recognizing the letters. Letters may look like strange squiggles; the individual letters themselves may have lost their connection to meaning. Again, additional information provided either through writing, gesture, speech, or pictures, can help the person understand the written word.

Other types of aphasia affect reading comprehension because verb forms and small “functor” words like prepositions and articles have lost their meaning. In this case, a person with aphasia would have more trouble understanding a sentence that is longer and more complex than a simpler sentence.

It is important to note that silent reading comprehension is different than being able to read out loud. Many people with aphasia can understand written words and sentences but be unable to read them out loud. We are used to teaching children to read by hearing them read out loud, and estimating their ability to read through how well they can do so. This is not the same in adults with aphasia who were able to read prior to their stroke or brain injury. It is important to test these two skills – silent reading comprehension and reading out loud – separately.

Norma

There is no single, agreed-upon definition of spirituality. Surveys of the definition of the term, as used in scholarly research, show a broad range of definitions, with very limited similitude.

It may denote almost any kind of meaningful activity or blissful experience. It denotes a process of transformation, but in a context separate from organized religious institutions, termed “spiritual but not religious”. In modern times the emphasis is on subjective experience. Houtman and Aupers suggest that modern spirituality is a blend of humanistic psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions.

Luc Paquin

Individuals with aphasia who have trouble understanding spoken language can have different kinds of problems.

Some individuals have more trouble at the beginning of listening to a message. This has been called slow rise time. If you are missing the beginning, you may have trouble following the rest of the message. One way to help this is to get the person’s attention first by calling their name and introducing the task. For example, you could say, “Let’s talk about our dinner plans tonight.” Then go on to say, “Tonight we are going to have dinner with our friends Mary and Joe.” This gives a “warm-up” to the topic.

Sometimes people with aphasia just don’t retrieve the meanings of the words being used fast enough or with enough certainty to understand the whole message. In this case, using a slower speech rate or repeating the message may help.

Sometimes people with aphasia hear the word, but the brain connects what is heard to a related word that is not really the one being said. For example, if you said: “I got a new cat”, it would be possible for the person with aphasia to think of a dog instead of a cat. This could lead the person with aphasia to say something like “Walking?” to ask if you are walking your new pet. This might seem strange to you, but is more easily understood when you realize that the person with aphasia linked the word “cat” that you said to the meaning “dog”. Paraphrasing with additional and alternative words can help. For example, you could say, “I got a new cat. She meows a lot but she also purrs a lot.” This extra information that helps to describe the cat will help the person with aphasia link to the meaning “cat”.

Sometimes people with aphasia hear the word, but it doesn’t sound to them like a real word. For example, if you say “Please put the book on the table”, the person with aphasia might hear “batle”. In that case, the person may not know where to put the book. Using gestures or additional information can help here. If you pointed to the table, or added some additional information like “the table by the chair”, this could help the person with aphasia understand.

Some people with aphasia understand most of the nouns that are being used in sentences, but have difficulties understanding the “little words”, verbs, and verb endings that form the grammar of what is said. For example, if you say “The girl with the red purse is being kissed by the boy”, this might be understood as “Girl – red purse – kiss – boy”. So, the person with this kind of auditory comprehension problem might understand that the girl with the red purse is kissing the boy – not being kissed by the boy. Articles, prepositions and other functor words – in this example, like the word “by” – are not processed. Something that can help here is to simplify the types of sentences that are being used. Break them into shorter sentences and avoid the use of lengthy, complex sentences.

Finally, some people with aphasia who have difficulty understanding what is said can read some words. So, it is helpful to write out key words on some scratch paper while you talk. For example, you could write the words “new cat” or “book – table” for the messages above.

Norma

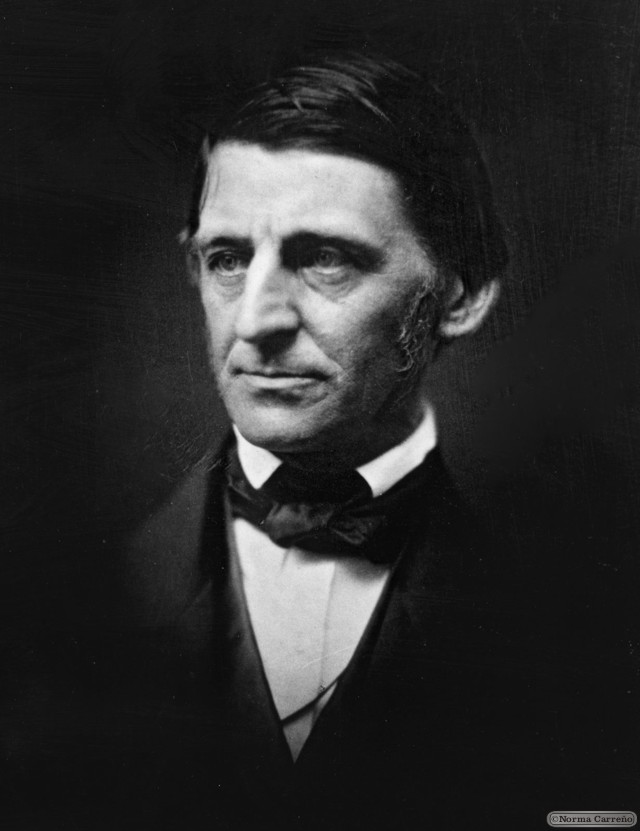

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, and poet who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United States.

Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of Transcendentalism in his 1836 essay, Nature. Following this ground-breaking work, he gave a speech entitled “The American Scholar” in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. considered to be America’s “Intellectual Declaration of Independence”.

Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first, then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays – Essays: First Series and Essays: Second Series, published respectively in 1841 and 1844 – represent the core of his thinking, and include such well-known essays as Self-Reliance, The Over-Soul, Circles, The Poet and Experience. Together with Nature, these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson’s most fertile period.

Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for humankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson’s “nature” was more philosophical than naturalistic: “Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul.” Emerson is one of several figures who “took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world.”

He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement, and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that have followed him. When asked to sum up his work, he said his central doctrine was “the infinitude of the private man.” Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of fellow Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau.

Final Years

Starting in 1867, Emerson’s health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals. Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, Emerson started having memory problems and suffered from aphasia. By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, “Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well”.

In the spring of 1871 Emerson took a trip on the transcontinental railroad, barely two years after its completion. Along the way and in California he met a number of dignitaries, including Brigham Young during a stopover in Salt Lake City. Part of his California visit included a trip to Yosemite, and while there he met a young and unknown John Muir, a signature event in Muir’s career.

Norma

It’s Amazing To See

It’s amazing to see stroke survivors who’ve lost the ability to speak suddenly produce accurate words when singing familiar songs. This phenomenon was first reported by Swedish physician Olaf Dalin in 1736. Dr. Dalin described a young man who had lost his ability to talk as a result of brain damage, but who surprised townsfolk by singing hymns in church.

The acquired language disorder now called “aphasia” became a subject of clinical study and a target for rehabilitation beginning in the mid-1880s. Since that time, every clinician working with aphasia has seen individuals who can produce words only when singing. Indeed, this observation prompted American neurologist Charles Mills to suggest (in 1904!) that it might help to play the piano and encourage patients with aphasia to sing well-known songs.

There appear to be psychological benefits, but singing familiar songs alone doesn’t seem to improve the speech of people with aphasia. This is probably because words that come automatically when singing are intricately linked to the melodies and are not easily separated.

The spoken word is a different matter. We know the brain has difficulty starting in the middle of highly memorized spoken passages (such as the “Pledge of Allegiance”). We need a “running start” to prime the pump of recall.

Songs themselves might be used to communicate. I had a patient who struggled to tell his son he wanted to go to a Boston Red Sox game. He finally got his point across by bursting forth with “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Unfortunately, there aren’t appropriate songs for every communication need, so it would be better if singing could be used to unblock residual speech abilities. This was the motivation for the aphasia treatment approach known as “Melodic Intonation Therapy,” which we began to develop in 1972.

Why Does It Work For Some People?

We know that aphasia typically results from a stroke or other damage that affects the left hemisphere of the brain, where language ability usually is located. We thought it might be because a stroke increased the use of the brain’s right hemisphere, where many aspects of music and the melody of speech are located. Using this treatment, the dominance of the damaged left hemisphere language areas might diminish while the right hemisphere became more involved.

A recent study using functional magnetic resonance imaging with individuals treated with melodic intonation therapy showed that the right hemisphere does, indeed, play a role in response to this method. Preliminary results suggest that the amount of speech recovery may be associated with how much and what part of the right hemisphere is activated. This study demonstrates the flexibility of adult brains, even those with stroke-related damage.

It is encouraging to know that with special treatment we can learn to use undamaged portions of our brains to perform “new tricks” – even one as complicated as speaking.

Trial And Error

Robert Sparks, a speech-language pathologist, Martin Albert, a behavioral neurologist, and I were working on the Aphasia Unit of the Boston VA Hospital. We saw a woman whose only purposeful speech was the combination of nonsense syllables: “nee-nee-nah-nah.”

At that time, a hospital volunteer was coming to each inpatient ward with a piano on wheels and conducting sing-along sessions with the patients. One day we observed our patient sitting beside him in her wheelchair and singing many of the words of popular songs. Though we had seen this before, this new example convinced us we had to try to develop a method that capitalized on this preserved ability to produce speech when singing.

We knew that simply singing familiar songs with this woman would not do the trick. Through trial and error, we discovered that if we melodically intoned everyday phrases such as “open the window” while helping her tap out the syllables with her unaffected hand, she could produce phrases in unison with us. Then she could intone the phrases with just a little help at the beginning. Finally, she could produce them on her own.

From this experience, we created a treatment program using melodically intoned and tapped out phrases of increasing length. Usually within a few sessions, patients’ production of nonsense syllables had disappeared and they began to communicate verbally in everyday situations. Our continued research helped identify the best candidates for this method.

Suggestions For Using Music With People With Aphasia

- Singing familiar songs is psychologically and emotionally uplifting. Provide opportunities for individuals with aphasia to sing their favorite songs. In addition to purchasing albums, put together tapes or CDs of their “all-time” favorites.

- It is now possible to legally purchase and download songs from the Internet to record them on CDs or digital MP3 players that store many songs.

Make singing a part of social events that might otherwise be difficult for a person with aphasia. Good candidates for melodic intonation therapy have:

- severely restricted speech that may be limited to nonsense words or syllables except when singing along to popular songs;

- poor ability to repeat words spoken by others;

- relatively good ability to understand the speech of others;

- good motivation, cooperation and attentiveness; and

- a single, left hemisphere lesion that spares Wernicke’s area (the speech comprehension center of the brain).

If this seems like a match, survivors should ask a speech-language pathologist to determine whether an individual with severely restricted speech output might be a good candidate for melodic intonation therapy. The program, including a manual, DVD and stimulus cards, can be implemented by family members.

Norma

Communication disorders that can appear following stroke or other brain injury include aphasia, apraxia of speech and oral apraxia. At times, it may be difficult to identify which of these conditions a survivor is dealing with, particularly since it is possible for all three to be present at the same time.

Aphasia is impairment in the ability to use or comprehend words.

It may cause difficulty:

- Understanding words.

- Finding the word to express a thought.

- Understanding grammatical sentences.

- Reading or writing words or sentences.

Therapy approaches for aphasia:

Restoring language ability

- Understanding spoken language

Example: Word/picture matching - Stimulating word finding

Example: Identify features of a target word to cue its name (i.e., size or shape)

Learning compensating communication methods

- Using writing or gestures

- Training conversation partners so they may adjust the way they communicate with persons with aphasia

Apraxia of speech (verbal apraxia) is difficulty initiating and executing voluntary movement patterns necessary to produce speech when there is no paralysis or weakness of speech muscles.

It may cause difficulty:

- Producing the desired speech sound.

- Using the correct rhythm and rate of speaking.

Therapy approaches:

Teaching sound production

- Repeating words

- Instruction on placement of oral structures

Teaching rhythm and rate

- Using a metronome or finger-snapping to keep time

- Prolonging duration of sentences

Providing an alternative or augmentative communication system that requires little or no speaking

- Low-tech system – Paper and pencil

- High-tech system – Computer program that produces voice output at keystroke

Oral apraxia, also referred to as nonverbal oral apraxia, is difficulty voluntarily moving the muscles of the lips, throat, soft palate and tongue for purposes other than speech, such as smiling or whistling. It may be difficult to carry out commands such as blowing a kiss, opening the mouth or puffing the cheeks. Because oral apraxia doesn’t affect speech or swallowing, it may not be treated by a speech-language pathologist.

Norma

Principles of CIT

Based on this theory, Taub developed a set of treatment principles designed to counteract learned non-use and enhance the underlying residual abilities of the impaired limb.

There were three treatment principles:

- 1. Constraint – avoid the compensation, in this case, by tying down the good limb (paw) of the animals he studied;

- 2. Forced use – require use of the impaired limb by placing the animals in circumstances where they needed to use it to achieve a meaningful goal (for example, acquiring food pellets); and

- 3. Massed practice – require the constraint and forced use every day and all day long.

In the last decade, Dr. Taub and many others have applied these three principles to humans. Results of these experiments suggest CIT is helpful in some cases. Emerging results of a randomized controlled trial by Dr. Steve Wolf of Emory University and others endorse the value of this approach at least with regard to arm rehabilitation.

CIT and Aphasia

Recently these same CIT principles have been applied to aphasia rehabilitation. In speech therapy, constraint means avoiding the use of compensatory strategies such as gesturing, drawing, writing, etc. Forced use means communicating only by talking; and massed practice refers to therapy occurring 2-4 hours per day.

The activities used in applying CIT principles to aphasia rehabilitation don’t differ substantially from what might be found in more traditional treatment approaches. However, what does differ are the demands placed on the speaker in the context of relevant, communicative exchange.

Preliminary investigations suggest that CIT principles may be effective in aphasia rehabilitation. However, this investigation is only beginning, and we are not able to say any more about its efficacy than that in some cases it appears to be helpful. Not only will further study be needed to confirm that CIT is effective with aphasia, these same studies are needed to confirm its safety. For example, some of the animal work by Dr. Tim Shallart and colleagues suggested that intensive CIT may be harmful when performed too early after a stroke. Thus the application of CIT to aphasia rehabilitation must be pursued with both enthusiasm and caution.

Evaluating new treatment approaches

Whenever a new intervention or approach to rehabilitation is considered, it is best to gather as much information as possible. Before beginning any rehabilitation program, you should determine that the provider is qualified, informed and experienced. However, when considering a product or program that is new or experimental, such as CIT applied to aphasia rehabilitation, it is equally important to evaluate how the program is portrayed and the evidence that supports it. Testimonials on promotional materials and uncontrolled case reports are considered the lowest level of evidence and should be supported by research published in professional journals.

Norma

Remember, when someone has aphasia:

- It is important to make the distinction between language and intelligence.

- Many people mistakenly think they are not as smart as they used to be.

- Their problem is that they cannot use language to communicate what they know.

- They can think, they just can’t say what they think.

- They can remember familiar faces.

- They can get from place to place.

- They still have political opinions, for example.

- They may still be able to play chess, for instance.

The challenge for all caregivers and health professionals is to provide people with aphasia a means to express what they know. Through intensive work in rehabilitation, gains can be made to avoid the frustration and isolation that aphasia can create.

For most, a stroke has a startling and life-altering effect on both the survivor and family members. All involved find themselves trying to come to terms with changes ranging from physical and sensory loss to loss of speech and language.

For many survivors, this loss or change in speech (dysarthria, apraxia) and language (aphasia) profoundly alters their social life. Ironically, research has shown that socializing is one of the best ways to maximize stroke recovery. Many experts contend that socializing should begin right away in the recovery process.

For many people living with aphasia, dysarthria or apraxia, the question then becomes: How can they socialize if they can’t communicate the way they used to?

Here are some tips you can use to begin your recovery:

- Educate yourself about aphasia so you can learn a new way to communicate.

- Close family members need to be involved so they can understand their loved one’s communication needs and begin to learn ways to facilitate speech and language.

- Experiment with strategies that facilitate social interaction during your rehabilitation.

- Many stroke survivors with communication challenges compensate by writing or drawing to supplement verbal expression, or use gestures or a picture communication book, or even a computer communication system.

Family members can facilitate communication with some simple techniques:

- Ask yes/no questions.

- Paraphrase periodically during conversation.

- Modify the length and complexity of conversations.

- Use gestures to emphasize important points.

- Establish a topic before beginning conversation.

Your environment also can help support successful socialization. Survivors have told us that it is easiest to begin practicing conversation in a one-on-one situation with someone they are comfortable with and who understands communication disorders.

In addition:

- Practice conversation in a quiet, distraction-free environment.

- As you become more confident, slowly add more conversational partners but continue to limit distractions such as background noise (music, other talking, TV).

- As you become more comfortable in one-to-one or small group interactions, explore less-controlled social situations with your speech-language pathologist, close friends and family, or other stroke survivors.

- Before you attend these gatherings, practice common things discussed in a variety of situations. For example, “How are you?” “It’s been a long time since I’ve seen you.”

Practice a few statements about current events: “Did you see the basketball game?” or “Boy, we are having beautiful weather!” - The more you practice this script, the greater your chances for success.

- Family members can prepare written cues, or organize pictures to promote interactions.

Once you achieve a level of comfort with close family and friends, you can start getting involved in the community by:

- Going to familiar large group activities such as church events or weekly social gatherings.

- Volunteering, returning to work or joining a new interest group.

- Remembering there’s no rush. You should step into this stage at a comfortable pace.

- Attending a stroke support group.

Speakeasy’s tips for communicating with speech and language limitations in social settings:

- Try, try, try to get your point across no matter what anybody says or thinks.

- If waiters speak too fast when you go out to dinner, ask them to slow down.

- Try one-on-one conversations.

- When talking on the phone with a new person, repeat, “I’m a stroke survivor… can you understand me?”

- Make a point to go out and interact with people – socializing is an important part of recovery.

- No matter who tells you that you can’t, it’s always possible to keep recovering!

Remember that the speech and language changes stroke survivors experience can last a lifetime in some form or another. As life circumstances change, and your speech and language needs evolve, reevaluate what works and what has not worked in social situations. And continue to expand your horizons.

Norma

Wernicke’s Aphasia (receptive)

People with serious comprehension difficulties have what is called Wernicke’s aphasia and:

- Often say many words that don’t make sense.

- May fail to realize they are saying the wrong words; for instance, they might call a fork a “gleeble.”

- May string together a series of meaningless words that sound like a sentence but don’t make sense.

- Have challenges because our dictionary of words is shelved in a similar region of the left hemisphere, near the area used for understanding words.

Broca’s Aphasia (expressive)

When a stroke injures the frontal regions of the left hemisphere, different kinds of language problems can occur. This part of the brain is important for putting words together to form complete sentences. Injury to the left frontal area can lead to what is called Broca’s aphasia. Survivors with Broca’s aphasia:

- Can have great difficulty forming complete sentences.

- May get out some basic words to get their message across, but leave out words like “is” or “the.”

- Often say something that doesn’t resemble a sentence.

- Can have trouble understanding sentences.

- Can make mistakes in following directions like “left, right, under, and after.”

“Car…bump…boom!” This is not a complete sentence, but it certainly expresses an important idea. Sometimes these individuals will say a word that is close to what they intend, but not the exact word; for example they may say “car” when they mean “truck.”

A speech pathologist friend mentioned to a patient that she was having a bad day. She said, “I was bitten by a dog.” The stroke survivor asked, “Why did you do that?” In this conversation, the patient understood the basic words spoken, but failed to realize that the words of the sentence and the order of the words were critical to interpreting the correct meaning of the sentence, that the dog bit the woman and not vice versa.

Global Aphasia

When a stroke affects an extensive portion of the front and back regions of the left hemisphere, the result may be global aphasia. Survivors with global aphasia:

- May have great difficulty in understanding words and sentences.

- May have great difficulty in forming words and sentences.

- May understand some words.

- Get out a few words at a time.

- Have severe difficulties that prevent them from effectively communicating.

Norma

Language is much more than words. It involves our ability to recognize and use words and sentences. Much of this capability resides in the left hemisphere of the brain. When a person has a stroke or other injury that affects the left side of the brain, it typically disrupts their ability to use language.

Through language, we:

- Communicate our inner thoughts, desires, intentions and motivations.

- Understand what others say to us.

- Ask questions.

- Give commands.

- Comment and interchange.

- Listen.

- Speak.

- Read.

- Write.

A stroke that affects the left side of the brain may lead to aphasia, a language impairment that makes it difficult to use language in those ways. Aphasia can have tragic consequences.

People with aphasia:

- May be disrupted in their ability to use language in ordinary circumstances.

- May have difficulty communicating in daily activities.

- May have difficulty communicating at home, in social situations, or at work.

- May feel isolated.

Scientists and clinicians who study how language is stored in the brain have learned that different aspects of language are located in different parts of the left hemisphere. For example, areas in the back portions allow us to understand words. When a stroke affects this posterior or back part of the left hemisphere, people can have great difficulty understanding what they hear or read.

Imagine going to a foreign country and hearing people speaking all around you. You would know they were using words and sentences. You might even have an elemental knowledge of that language, allowing you to recognize words here and there, but you would not have command of the language and couldn’t follow most conversation. This is what life is like for people with comprehension problems.

People with comprehension problems:

- Know that people are speaking to them.

- Can follow some of the melody of sentences – realizing if someone is asking a question or expressing anger.

- May have great difficulty understanding specific words.

- May have great difficulty understanding how words go together to convey a complete thought.

Norma