Family

Family

René Descartes (31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician, and scientist who spent most of his life in the Dutch Republic.

He has been dubbed the father of modern philosophy, and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day. In particular, his Meditations on First Philosophy continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes’s influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system – allowing reference to a point in space as a set of numbers, and allowing algebraic equations to be expressed as geometric shapes in a two- or three-dimensional coordinate system (and conversely, shapes to be described as equations) – was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the scientific revolution and has been described as an example of genius.

Descartes refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers, and refused to trust his own senses. He frequently set his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, a treatise on the early modern version of what are now commonly called emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic “as if no one had written on these matters before”. Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differs from the schools on two major points: First, he rejects the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejects any appeal to final ends – divine or natural – in explaining natural phenomena. In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God’s act of creation.

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza and Descartes were all well versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

His best known philosophical statement is “Cogito ergo sum” (French: Je pense, donc je suis; I think, therefore I am), found in part IV of Discourse on the Method (1637 – written in French but with inclusion of “Cogito ergo sum”) and §7 of part I of Principles of Philosophy (1644 – written in Latin).

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

“Martial Morality”

Traditional Chinese schools of martial arts, such as the famed Shaolin monks, often dealt with the study of martial arts not just as a means of self-defense or mental training, but as a system of ethics. Wude can be translated as “martial morality” and is constructed from the words wu, which means martial, and de, which means morality. Wude deals with two aspects; “morality of deed” and “morality of mind”. Morality of deed concerns social relations; morality of mind is meant to cultivate the inner harmony between the emotional mind (Xin) and the wisdom mind (Hui). The ultimate goal is reaching “no extremity” (Wuji) – closely related to the Taoist concept of wu wei – where both wisdom and emotions are in harmony with each other.

Virtues:

Deed

- Humility: Qian

- Virtue: Cheng

- Respect: Li

- Morality: Yi

- Trust: Xin

Mind

- Courage: Yong

- Patience: Ren

- Endurance: Heng

- Perseverance: Yi

- Will: Zhi

Luc Paquin

Aurora was a family physician with a busy practice when she suffered a massive stroke in 2006. “This place (Aphasia Institute) has given us hope and a support system”.

Aurora was a family physician with a busy practice when she suffered a massive stroke in 2006. Hoping that the Aphasia Institute might be able to help his wife, her husband Buddy brought an unresponsive Aurora to the Institute’s Introductory Program. Aurora sat slumped in her wheelchair, barely looking at her communication partner throughout the first session but over the course of the program, glimmers of hope began to emerge. Volunteers and staff were able to engage Aurora and prompt her to look up when in conversation – she even started initiating chats.

Through supportive Institute programs, Aurora and Buddy worked together to develop new skills and today Aurora continues to thrive, communicating her thoughts and asserting her desires and wants at home. Although their lives have been forever changed, “this place (Aphasia Institute) has given us hope and a support system,” says Buddy.

Aurora and Buddy

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Wushu

The word wu is translated as ‘martial’ in English, however in terms of etymology, this word has a slightly different meaning. In Chinese, wu is made of two parts; the first meaning “stop” (zhi) and the second meaning “invaders lance” (je). This implies that “wu’” is a defensive use of combat. The term “wushu” meaning “martial arts” goes back as far as the Liang Dynasty (502-557) in an anthology compiled by Xiao Tong, (Prince Zhaoming; d. 531), called Selected Literature (Wenxian). The term is found in the second verse of a poem by Yan Yanzhi titled: “Huang Taizi Shidian Hui Zuoshi”.

- “The great man grows the many myriad things . . .

Breaking away from the military arts,

He promotes fully the cultural mandates.”

(Translation from: Echoes of the Past by Yan Yanzhi (384-456))

The term wushu is also found in a poem by Cheng Shao (1626-1644) from the Ming Dynasty.

The earliest term for ‘martial arts’ can be found in the Han History (206BC-23AD) was “military fighting techniques” (bing jiqiao). During the Song period (c.960) the name changed to “martial arts” (wuyi). In 1928 the name was changed to “national arts” (guoshu) when the National Martial Arts Academy was established in Nanjing. The term reverted to wushu under the People’s Republic of China during the early 1950s.

As forms have grown in complexity and quantity over the years, and many forms alone could be practiced for a lifetime, modern styles of Chinese martial arts have developed that concentrate solely on forms, and do not practice application at all. These styles are primarily aimed at exhibition and competition, and often include more acrobatic jumps and movements added for enhanced visual effect compared to the traditional styles. Those who generally prefer to practice traditional styles, focused less on exhibition, are often referred to as traditionalists. Some traditionalists consider the competition forms of today’s Chinese martial arts as too commercialized and losing much of its original values.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Controversy

Even though forms in Chinese martial arts are intended to depict realistic martial techniques, the movements are not always identical to how techniques would be applied in combat. Many forms have been elaborated upon, on the one hand to provide better combat preparedness, and on the other hand to look more aesthetically pleasing. One manifestation of this tendency toward elaboration beyond combat application is the use of lower stances and higher, stretching kicks. These two maneuvers are unrealistic in combat and are used in forms for exercise purposes. Many modern schools have replaced practical defense or offense movements with acrobatic feats that are more spectacular to watch, thereby gaining favor during exhibitions and competitions. This has led to criticisms by traditionalists of the endorsement of the more acrobatic, show-oriented Wushu competition. Even though appearance has always been important in many traditional forms as well, all patterns exist for their combat functionality. Historically forms were often performed for entertainment purposes long before the advent of modern Wushu as practitioners have looked for supplementary income by performing on the streets or in theaters. As documented in ancient literature during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) suggest some sets, (including two + person sets: dui da also called dui lian) became very elaborate and ‘flowery’, many mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire category of martial arts known as Hua Fa Wuyi. During the Northern Song period, it was noted by historians this type of training had a negative influence on training in the military.

Many traditional Chinese martial artists, as well as practitioners of modern sport combat, have become critical of the perception that forms work is more relevant to the art than sparring and drill application, while most continue to see traditional forms practice within the traditional context – as vital to both proper combat execution, the Shaolin aesthetic as art form, as well as upholding the meditative function of the physical art form.

Another reason why techniques often appear different in forms when contrasted with sparring application is thought by some to come from the concealment of the actual functions of the techniques from outsiders.

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

Traditional “sparring” sets, called dui da or dui lian, were an important part of Chinese martial arts for centuries. Dui lian literally means, to train by a pair of combatants opposing each other – the character lian, means to practice; to train; to perfect one’s skill; to drill. As well, often one of these terms are also included in the name of fighting sets (shuang yan), “paired practice” (zheng sheng), “to struggle with strength for victory” (di), match – the character suggests to strike an enemy; and “to break” (po).

Generally there are 21, 18, 12, 9 or 5 drills or ‘exchanges/groupings’ of attacks and counterattacks, in each dui lian set. These drills were considered only generic patterns and never meant to be considered inflexible ‘tricks’. Students practiced smaller parts/exchanges, individually with opponents switching sides in a continuous flow. Basically, dui lian were not only a sophisticated and effective methods of passing on the fighting knowledge of the older generation, they were important and effective training methods. The relationship between single sets and contact sets is complicated, in that some skills cannot be developed with single sets, and, conversely, with dui lian. Unfortunately, it appears that most traditional combat oriented dui lian and their training methodology have disappeared, especially those concerning weapons. There are a number of reasons for this. In modern Chinese martial arts most of the dui lian are recent inventions designed for light props resembling weapons, with safety and drama in mind. The role of this kind of training has degenerated to the point of being useless in a practical sense, and, at best, is just performance.

By the early Song period, sets were not so much “individual isolated technique strung together” but rather were composed of techniques and counter technique groupings. It is quite clear that “sets” and “fighting (2 person) sets” have been instrumental in TCM for many hundreds of years – even before the Song Dynasty. There are images of two person weapon training in Chinese stone painting going back at least to the Eastern Han Dynasty.

According to what has been passed on by the older generations, the approximate ratio of contact sets to single sets was approximately 1:3. In other words, about 30% of the sets practiced at Shaolin were contact sets, dui lian, and two person drill training. This is, in part, evidenced by the Qing Dynasty mural at Shaolin.

Ancient literature from the Tang and Northern Song Dynasties suggests that some sets, including those that required two or more participants, became very elaborate and mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire new category of martial arts known as “fancy patterns for developing military skill” (Hua Fa Wuyi). During the Northern Song period it was noted by historians that this phenomenon had a negative influence on training in the military.

For most of its history, Shaolin martial arts was largely weapon-focused: staves were used to defend the monastery, not bare hands. Even the more recent military exploits of Shaolin during the Ming and Qing Dynasties involved weapons. According to some traditions, monks first studied basics for one year and were then taught staff fighting so that they could protect the monastery. Although wrestling has been as sport in China for centuries, weapons have been the most important part of Chinese wushu since ancient times. If one wants to talk about recent or ‘modern’ developments in Chinese martial arts (including Shaolin for that matter), it is the over-emphasis on bare hand fighting. During the Northern Song Dynasty (976-997 A.D) when platform fighting known as Da Laitai (Title Fights Challenge on Platform) first appeared, these fights were with only swords and staves. Although later, when bare hand fights appeared as well, it was the weapons events that became the most famous. These open-ring competitions had regulations and were organized by government organizations; some were also organized by the public. The government competitions resulted in appointments to military posts for winners and were held in the capital as well as in the prefectures.

Luc Paquin

In 2006, Dr. Donald Meeks was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

Dr. Donald Meeks dedicated his life to helping people with addictions, building a distinguished reputation as a Professor at the University of Toronto and the Associate Director of the Clinical Institute at the Centre for Mental Health and Addiction (CAMH). His work took him around the world as a special consultant to the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

In 2006, he was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

After the second stroke, Don was left with lingering weakness on his right side, permanent damage to his memory, and aphasia.

For an academic man who had built his career on his ability to read, write and express himself verbally, aphasia was an unexpected blow. “I suffered the most from a lack of self confidence in pubic situations – I feared that I would be inarticulate or lose my train of thought,” says Don. “Being referred to the Aphasia Institute was a ‘stroke of luck’!”

Don and his wife Sherril entered the Aphaisa Institute’s Introductory Program with great hope… and the program delivered. Don’s confidence began to build and Sherril connected with fellow caregivers and built a network of support for herself. Together, they learned about aphasia and some of the supportive communication techniques.

Don quickly graduated to the Aphasia Institute’s Toastmasters Club, where he continues today. Sherril remains connected to the Family group. Both are looking ahead with optimism although they appreciate that the journey has been very different for each of them.

Looking back, there’s an irony to having spent decades helping others only to find themselves, as Don refers to it, ‘on the other side of the gurney’.

Both know that the Aphasia Institute will be a key part of their lives for some time to come. “This is a best practice demonstration of everything I taught for years,” says Don. “The community at AI is astounding – we feel so welcomed and very much a part of this wonderful, wonderful community.”

Dr. Donald Meeks

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms or taolu (Pinyin: tàolù) in Chinese are series of predetermined movements combined so they can be practiced as a continuous set of movements. Forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a particular style branch, and were often taught to advanced students selected for that purpose. Forms contained both literal, representative and exercise-oriented forms of applicable techniques that students could extract, test, and train in through sparring sessions.

Today, many consider forms to be one of the most important practices in Chinese martial arts. Traditionally, they played a smaller role in training for combat application, and took a back seat to sparring, drilling and conditioning. Forms gradually build up a practitioner’s flexibility, internal and external strength, speed and stamina, and they teach balance and coordination. Many styles contain forms that use weapons of various lengths and types, using one or two hands. Some styles focus on a certain type of weapon. Forms are meant to be both practical, usable, and applicable as well as to promote fluid motion, meditation, flexibility, balance, and coordination. Teachers are often heard to say “train your form as if you were sparring and spar as if it were a form.”

There are two general types of forms in Chinese martial arts. Most common are solo forms performed by a single student. There are also sparring forms – choreographed fighting sets performed by two or more people. Sparring forms were designed both to acquaint beginning fighters with basic measures and concepts of combat, and to serve as performance pieces for the school. Weapons-based sparring forms are especially useful for teaching students the extension, range, and technique required to manage a weapon.

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

The term taolu is a shorten version of Tao Lu Yun Dong, an expression introduced only recently with the popularity of modern wushu. This expression refers to “exercise sets” and is used in the context of athletics or sport.

In contrast, in traditional Chinese martial arts alternative terminologies for the training of “sets or forms” are:

- Lian Quan Tao – Practicing sequence of fist

- Lian Quan Jiao – Practicing fists and feet

- Lian Bing Qi – Practicing weapons

- Dui Da and Dui Lian – Fighting sets

Luc Paquin

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Weapons Training

Most Chinese styles also make use of training in the broad arsenal of Chinese weapons for conditioning the body as well as coordination and strategy drills. Weapons training (qìxiè) are generally carried out after the student is proficient in the basics, forms and applications training. The basic theory for weapons training is to consider the weapon as an extension of the body. It has the same requirements for footwork and body coordination as the basics. The process of weapon training proceeds with forms, forms with partners and then applications. Most systems have training methods for each of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu (shíbabanbingqì) in addition to specialized instruments specific to the system.

Application

Application refers to the practical use of combative techniques. Chinese martial arts techniques are ideally based on efficiency and effectiveness. Application includes non-compliant drills, such as Pushing Hands in many internal martial arts, and sparring, which occurs within a variety of contact levels and rule sets.

When and how applications are taught varies from style to style. Today, many styles begin to teach new students by focusing on exercises in which each student knows a prescribed range of combat and technique to drill on. These drills are often semi-compliant, meaning one student does not offer active resistance to a technique, in order to allow its demonstrative, clean execution. In more resisting drills, fewer rules apply, and students practice how to react and respond. ‘Sparring’ refers to the most important aspect of application training, which simulates a combat situation while including rules that reduce the chance of serious injury.

Competitive sparring disciplines include Chinese kickboxing Sanshou and Chinese folk wrestling Shuaijiao, which were traditionally contested on a raised platform arena Lèitái. Lèitái represents public challenge matches that first appeared in the Song Dynasty. The objective for those contests was to knock the opponent from a raised platform by any means necessary. San Shou represents the modern development of Lei Tai contests, but with rules in place to reduce the chance of serious injury. Many Chinese martial art schools teach or work within the rule sets of Sanshou, working to incorporate the movements, characteristics, and theory of their style. Chinese martial artists also compete in non-Chinese or mixed Combat sport, including boxing, kickboxing and Mixed martial arts.

Luc Paquin

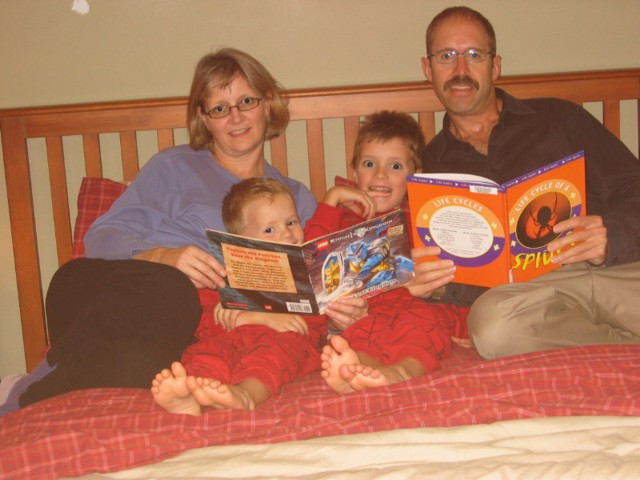

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys.

The Ardiel family piles into their big bed for a favourite nightly ritual. Jane reads a storybook aloud to her boys and husband while running her index finger along the page under the words so six-year old Ben can follow along. Sometimes Ben reads a page. Aiden, at four-years old is too young to read so he snuggles in to enjoy the tale. For dad Scott, although reading a sentence aloud is a struggle, he participates as fully as he can in this bonding family routine.

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys. “[Aphasia] , that’s been a struggle from the beginning. [I] can’t tell [the boys how to do things], but I have to show them,” says Scott.

Even though Scott knows what he wants to say, he has difficulty expressing it. Sometimes he finds it hard to understand what others are saying and reading can be difficult. Scott and Jane found the Aphasia Institute to be a “nugget of hope” once Scott was released from rehab after his stroke. They found comfort in an environment that understood the impact aphasia had on the whole family.

Jane joined the Family Support and Education Group and found a community that empathized with her experience.

Today Scott is a member of the Toastmaster Aphasia Gavel Club and an active volunteer at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. Jane has made it her mission to educate every medical professional they have encountered along this journey about aphasia.

“Much of my own healing through this experience has come from the opportunity to help others. There’s a saying – we achieve happiness when we seek the happiness and wellbeing of others,” says Jane.

Jane & Scott Ardiel

Norma