Family

Family

Some people with aphasia may have trouble thinking of the word that they want to write, even though they know the meaning or message that they want to communicate. In this case, the person will not be able to write the word or say it, because they cannot think of the word itself. We have all experienced this kind of problem, often called “tip of the tongue”. You know the name of a person, place, or object, you can picture it clearly, you can describe it, but you just can’t think of the name of it. When this happens to you, you can neither say the word nor write it.

In other cases, the person with aphasia may know the word that they would like to write, and they might be able to say it, but they can’t write it. In this case, the sounds that need to be put together to say the word are accessible, but the spelling of the word is not. This may seem odd to those of us without aphasia. Our abilities to pronounce words and write them are so closely intertwined that it is hard for us to imagine being able to do one but not the other. But that is what can happen in aphasia.

Sometimes certain kinds of information about the word is available. Sometimes a related word might end up being written, for example, writing “apple” when you want to write “banana”. Other times the person with aphasia might be able to write the first letter, or draw slots for how many letters are in the word, or write the first and last letters, but make mistakes on the remaining letters. In this case, preserved information about what the written word looks like is there, but it’s not complete.

Some people with aphasia might write extra letters or words, or even write down non-words.

Finally, some people who have a nonfluent type of aphasia might be able to write some words but omit “little” words or have more trouble with verbs. They will have more trouble writing sentences.

Norma

Classical, medieval and early modern periods

Words translatable as ‘spirituality’ first began to arise in the 5th century and only entered common use toward the end of the Middle Ages. In a Biblical context the term means being animated by God, to be driven by the Holy Spirit, as opposed to a life which rejects this influence.

In the 11th century this meaning changed. Spirituality began to denote the mental aspect of life, as opposed to the material and sensual aspects of life, “the ecclesiastical sphere of light against the dark world of matter”. In the 13th century “spirituality” acquired a social and psychological meaning. Socially it denoted the territory of the clergy: “The ecclesiastical against the temporary possessions, the ecclesiastical against the secular authority, the clerical class against the secular class”. Psychologically, it denoted the realm of the inner life: “The purity of motives, affections, intentions, inner dispositions, the psychology of the spiritual life, the analysis of the feelings”.

In the 17th and 18th century a distinction was made between higher and lower forms of spirituality: “A spiritual man is one who is Christian ‘more abundantly and deeper than others’.” The word was also associated with mysticism and quietism, and acquired a negative meaning.

Luc Paquin

Make the Connection

Taking the path less traveled by exploring your spirituality can lead to a clearer life purpose, better personal relationships and enhanced stress management skills.

Some stress relief tools are very tangible: exercising more, eating healthy foods and talking with friends. A less tangible – but no less useful – way to find stress relief is through spirituality.

What is Spirituality?

Spirituality has many definitions, but at its core spirituality helps to give our lives context. It’s not necessarily connected to a specific belief system or even religious worship. Instead, it arises from your connection with yourself and with others, the development of your personal value system, and your search for meaning in life.

For many, spirituality takes the form of religious observance, prayer, meditation or a belief in a higher power. For others, it can be found in nature, music, art or a secular community. Spirituality is different for everyone.

How can spirituality help with stress relief?

Spirituality has many benefits for stress relief and overall mental health. It can help you:

- Feel a sense of purpose. Cultivating your spirituality may help uncover what’s most meaningful in your life. By clarifying what’s most important, you can focus less on the unimportant things and eliminate stress.

- Connect to the world. The more you feel you have a purpose in the world, the less solitary you feel – even when you’re alone. This can lead to a valuable inner peace during difficult times.

- Release control. When you feel part of a greater whole, you realize that you aren’t responsible for everything that happens in life. You can share the burden of tough times as well as the joys of life’s blessings with those around you.

- Expand your support network. Whether you find spirituality in a church, mosque or synagogue, in your family, or in nature walks with a friend, this sharing of spiritual expression can help build relationships.

- Lead a healthier life. People who consider themselves spiritual appear to be better able to cope with stress and heal from illness or addiction faster.

Discovering your Spirituality

Uncovering your spirituality may take some self-discovery. Here are some questions to ask yourself to discover what experiences and values define you:

- What are your important relationships?

- What do you value most in your life?

- What people give you a sense of community?

- What inspires you and gives you hope?

- What brings you joy?

- What are your proudest achievements?

The answers to such questions help you identify the most important people and experiences in your life. With this information, you can focus your search for spirituality on the relationships and activities in life that have helped define you as a person and those that continue to inspire your personal growth.

Luc Paquin

Some people with aphasia have difficulty processing the written words that they see.

It is possible for a person with aphasia to look at one word, for example, “fork”, and think of a spoon or something else related to “fork”. Another kind of problem is to look at a written word and fail to recognize it in any meaningful way. For example, a person with aphasia could look at a written word like “fork” and not be able to think what it means. In these cases, it is helpful to add additional written information, gesture, or pictures, to help reading comprehension. Compare the following two statements: “Get the spoon” and “Get the spoon – the one for soup”. In the second statement there is additional information that may help trigger the correct meaning of the target, “spoon”. Even though the second statement is longer, it provides redundancy which helps comprehension.

Some people with aphasia have trouble recognizing the letters. Letters may look like strange squiggles; the individual letters themselves may have lost their connection to meaning. Again, additional information provided either through writing, gesture, speech, or pictures, can help the person understand the written word.

Other types of aphasia affect reading comprehension because verb forms and small “functor” words like prepositions and articles have lost their meaning. In this case, a person with aphasia would have more trouble understanding a sentence that is longer and more complex than a simpler sentence.

It is important to note that silent reading comprehension is different than being able to read out loud. Many people with aphasia can understand written words and sentences but be unable to read them out loud. We are used to teaching children to read by hearing them read out loud, and estimating their ability to read through how well they can do so. This is not the same in adults with aphasia who were able to read prior to their stroke or brain injury. It is important to test these two skills – silent reading comprehension and reading out loud – separately.

Norma

Definition

There is no single, widely-agreed definition of spirituality. Surveys of the definition of the term, as used in scholarly research, show a broad range of definitions, with very limited similitude.

According to Waaijman, the traditional meaning of spirituality is a process of re-formation which “aims to recover the original shape of man, the image of God. To accomplish this, the re-formation is oriented at a mold, which represents the original shape: in Judaism the Torah, in Christianity Christ, in Buddhism Buddha, in the Islam Muhammad.”

In modern times the emphasis is on subjective experience. It may denote almost any kind of meaningful activity or blissful experience. It still denotes a process of transformation, but in a context separate from organized religious institutions, termed “spiritual but not religious”. Houtman and Aupers suggest that modern spirituality is a blend of humanistic psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions.

Waaijman points out that “spirituality” is only one term of a range of words which denote the praxis of spirituality. Some other terms are “Hasidism, contemplation, kabbala, asceticism, mysticism, perfection, devotion and piety”.

Etymology

The term spirit means “animating or vital principle in man and animals”. It is derived from the Old French espirit which comes from the Latin word spiritus (soul, courage, vigor, breath) and is related to spirare (to breathe). In the Vulgate the Latin word spiritus is used to translate the Greek pneuma and Hebrew ruah.

The term “spiritual”, matters “concerning the spirit”, is derived from Old French spirituel, which is derived from Latin spiritualis, which comes from spiritus or “spirit”.

The term “spirituality” is derived from Middle French spiritualité, from Late Latin “spiritualitatem” (nominative spiritualitas), which is also derived from Latin spiritualis.

Luc Paquin

There is no single, agreed-upon definition of spirituality. Surveys of the definition of the term, as used in scholarly research, show a broad range of definitions, with very limited similitude.

It may denote almost any kind of meaningful activity or blissful experience. It denotes a process of transformation, but in a context separate from organized religious institutions, termed “spiritual but not religious”. In modern times the emphasis is on subjective experience. Houtman and Aupers suggest that modern spirituality is a blend of humanistic psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions.

Luc Paquin

Individuals with aphasia who have trouble understanding spoken language can have different kinds of problems.

Some individuals have more trouble at the beginning of listening to a message. This has been called slow rise time. If you are missing the beginning, you may have trouble following the rest of the message. One way to help this is to get the person’s attention first by calling their name and introducing the task. For example, you could say, “Let’s talk about our dinner plans tonight.” Then go on to say, “Tonight we are going to have dinner with our friends Mary and Joe.” This gives a “warm-up” to the topic.

Sometimes people with aphasia just don’t retrieve the meanings of the words being used fast enough or with enough certainty to understand the whole message. In this case, using a slower speech rate or repeating the message may help.

Sometimes people with aphasia hear the word, but the brain connects what is heard to a related word that is not really the one being said. For example, if you said: “I got a new cat”, it would be possible for the person with aphasia to think of a dog instead of a cat. This could lead the person with aphasia to say something like “Walking?” to ask if you are walking your new pet. This might seem strange to you, but is more easily understood when you realize that the person with aphasia linked the word “cat” that you said to the meaning “dog”. Paraphrasing with additional and alternative words can help. For example, you could say, “I got a new cat. She meows a lot but she also purrs a lot.” This extra information that helps to describe the cat will help the person with aphasia link to the meaning “cat”.

Sometimes people with aphasia hear the word, but it doesn’t sound to them like a real word. For example, if you say “Please put the book on the table”, the person with aphasia might hear “batle”. In that case, the person may not know where to put the book. Using gestures or additional information can help here. If you pointed to the table, or added some additional information like “the table by the chair”, this could help the person with aphasia understand.

Some people with aphasia understand most of the nouns that are being used in sentences, but have difficulties understanding the “little words”, verbs, and verb endings that form the grammar of what is said. For example, if you say “The girl with the red purse is being kissed by the boy”, this might be understood as “Girl – red purse – kiss – boy”. So, the person with this kind of auditory comprehension problem might understand that the girl with the red purse is kissing the boy – not being kissed by the boy. Articles, prepositions and other functor words – in this example, like the word “by” – are not processed. Something that can help here is to simplify the types of sentences that are being used. Break them into shorter sentences and avoid the use of lengthy, complex sentences.

Finally, some people with aphasia who have difficulty understanding what is said can read some words. So, it is helpful to write out key words on some scratch paper while you talk. For example, you could write the words “new cat” or “book – table” for the messages above.

Norma

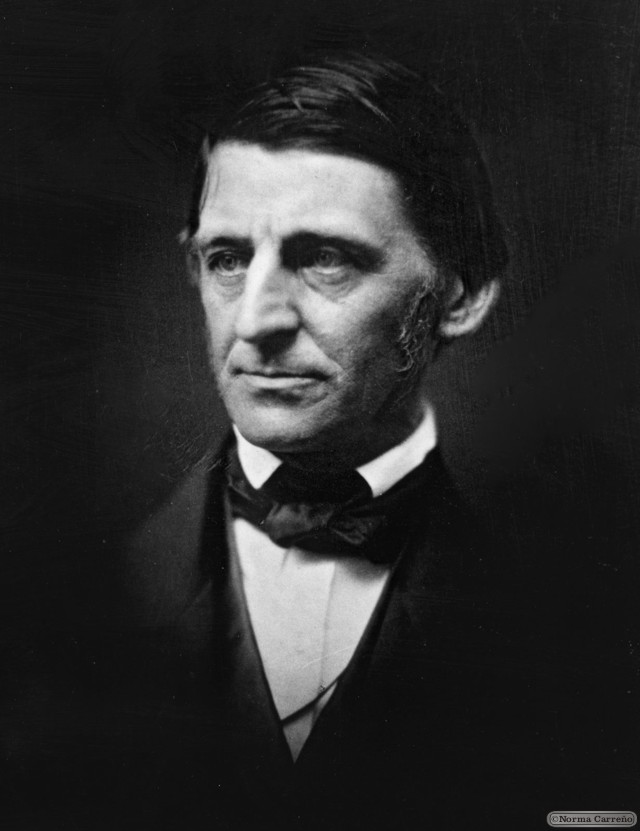

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, and poet who led the Transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United States.

Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of Transcendentalism in his 1836 essay, Nature. Following this ground-breaking work, he gave a speech entitled “The American Scholar” in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. considered to be America’s “Intellectual Declaration of Independence”.

Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first, then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays – Essays: First Series and Essays: Second Series, published respectively in 1841 and 1844 – represent the core of his thinking, and include such well-known essays as Self-Reliance, The Over-Soul, Circles, The Poet and Experience. Together with Nature, these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson’s most fertile period.

Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for humankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson’s “nature” was more philosophical than naturalistic: “Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul.” Emerson is one of several figures who “took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world.”

He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement, and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that have followed him. When asked to sum up his work, he said his central doctrine was “the infinitude of the private man.” Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of fellow Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau.

Final Years

Starting in 1867, Emerson’s health began declining; he wrote much less in his journals. Beginning as early as the summer of 1871 or in the spring of 1872, Emerson started having memory problems and suffered from aphasia. By the end of the decade, he forgot his own name at times and, when anyone asked how he felt, he responded, “Quite well; I have lost my mental faculties, but am perfectly well”.

In the spring of 1871 Emerson took a trip on the transcontinental railroad, barely two years after its completion. Along the way and in California he met a number of dignitaries, including Brigham Young during a stopover in Salt Lake City. Part of his California visit included a trip to Yosemite, and while there he met a young and unknown John Muir, a signature event in Muir’s career.

Norma

It’s Amazing To See

It’s amazing to see stroke survivors who’ve lost the ability to speak suddenly produce accurate words when singing familiar songs. This phenomenon was first reported by Swedish physician Olaf Dalin in 1736. Dr. Dalin described a young man who had lost his ability to talk as a result of brain damage, but who surprised townsfolk by singing hymns in church.

The acquired language disorder now called “aphasia” became a subject of clinical study and a target for rehabilitation beginning in the mid-1880s. Since that time, every clinician working with aphasia has seen individuals who can produce words only when singing. Indeed, this observation prompted American neurologist Charles Mills to suggest (in 1904!) that it might help to play the piano and encourage patients with aphasia to sing well-known songs.

There appear to be psychological benefits, but singing familiar songs alone doesn’t seem to improve the speech of people with aphasia. This is probably because words that come automatically when singing are intricately linked to the melodies and are not easily separated.

The spoken word is a different matter. We know the brain has difficulty starting in the middle of highly memorized spoken passages (such as the “Pledge of Allegiance”). We need a “running start” to prime the pump of recall.

Songs themselves might be used to communicate. I had a patient who struggled to tell his son he wanted to go to a Boston Red Sox game. He finally got his point across by bursting forth with “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Unfortunately, there aren’t appropriate songs for every communication need, so it would be better if singing could be used to unblock residual speech abilities. This was the motivation for the aphasia treatment approach known as “Melodic Intonation Therapy,” which we began to develop in 1972.

Why Does It Work For Some People?

We know that aphasia typically results from a stroke or other damage that affects the left hemisphere of the brain, where language ability usually is located. We thought it might be because a stroke increased the use of the brain’s right hemisphere, where many aspects of music and the melody of speech are located. Using this treatment, the dominance of the damaged left hemisphere language areas might diminish while the right hemisphere became more involved.

A recent study using functional magnetic resonance imaging with individuals treated with melodic intonation therapy showed that the right hemisphere does, indeed, play a role in response to this method. Preliminary results suggest that the amount of speech recovery may be associated with how much and what part of the right hemisphere is activated. This study demonstrates the flexibility of adult brains, even those with stroke-related damage.

It is encouraging to know that with special treatment we can learn to use undamaged portions of our brains to perform “new tricks” – even one as complicated as speaking.

Trial And Error

Robert Sparks, a speech-language pathologist, Martin Albert, a behavioral neurologist, and I were working on the Aphasia Unit of the Boston VA Hospital. We saw a woman whose only purposeful speech was the combination of nonsense syllables: “nee-nee-nah-nah.”

At that time, a hospital volunteer was coming to each inpatient ward with a piano on wheels and conducting sing-along sessions with the patients. One day we observed our patient sitting beside him in her wheelchair and singing many of the words of popular songs. Though we had seen this before, this new example convinced us we had to try to develop a method that capitalized on this preserved ability to produce speech when singing.

We knew that simply singing familiar songs with this woman would not do the trick. Through trial and error, we discovered that if we melodically intoned everyday phrases such as “open the window” while helping her tap out the syllables with her unaffected hand, she could produce phrases in unison with us. Then she could intone the phrases with just a little help at the beginning. Finally, she could produce them on her own.

From this experience, we created a treatment program using melodically intoned and tapped out phrases of increasing length. Usually within a few sessions, patients’ production of nonsense syllables had disappeared and they began to communicate verbally in everyday situations. Our continued research helped identify the best candidates for this method.

Suggestions For Using Music With People With Aphasia

- Singing familiar songs is psychologically and emotionally uplifting. Provide opportunities for individuals with aphasia to sing their favorite songs. In addition to purchasing albums, put together tapes or CDs of their “all-time” favorites.

- It is now possible to legally purchase and download songs from the Internet to record them on CDs or digital MP3 players that store many songs.

Make singing a part of social events that might otherwise be difficult for a person with aphasia. Good candidates for melodic intonation therapy have:

- severely restricted speech that may be limited to nonsense words or syllables except when singing along to popular songs;

- poor ability to repeat words spoken by others;

- relatively good ability to understand the speech of others;

- good motivation, cooperation and attentiveness; and

- a single, left hemisphere lesion that spares Wernicke’s area (the speech comprehension center of the brain).

If this seems like a match, survivors should ask a speech-language pathologist to determine whether an individual with severely restricted speech output might be a good candidate for melodic intonation therapy. The program, including a manual, DVD and stimulus cards, can be implemented by family members.

Norma

Communication disorders that can appear following stroke or other brain injury include aphasia, apraxia of speech and oral apraxia. At times, it may be difficult to identify which of these conditions a survivor is dealing with, particularly since it is possible for all three to be present at the same time.

Aphasia is impairment in the ability to use or comprehend words.

It may cause difficulty:

- Understanding words.

- Finding the word to express a thought.

- Understanding grammatical sentences.

- Reading or writing words or sentences.

Therapy approaches for aphasia:

Restoring language ability

- Understanding spoken language

Example: Word/picture matching - Stimulating word finding

Example: Identify features of a target word to cue its name (i.e., size or shape)

Learning compensating communication methods

- Using writing or gestures

- Training conversation partners so they may adjust the way they communicate with persons with aphasia

Apraxia of speech (verbal apraxia) is difficulty initiating and executing voluntary movement patterns necessary to produce speech when there is no paralysis or weakness of speech muscles.

It may cause difficulty:

- Producing the desired speech sound.

- Using the correct rhythm and rate of speaking.

Therapy approaches:

Teaching sound production

- Repeating words

- Instruction on placement of oral structures

Teaching rhythm and rate

- Using a metronome or finger-snapping to keep time

- Prolonging duration of sentences

Providing an alternative or augmentative communication system that requires little or no speaking

- Low-tech system – Paper and pencil

- High-tech system – Computer program that produces voice output at keystroke

Oral apraxia, also referred to as nonverbal oral apraxia, is difficulty voluntarily moving the muscles of the lips, throat, soft palate and tongue for purposes other than speech, such as smiling or whistling. It may be difficult to carry out commands such as blowing a kiss, opening the mouth or puffing the cheeks. Because oral apraxia doesn’t affect speech or swallowing, it may not be treated by a speech-language pathologist.

Norma