Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

Traditional “sparring” sets, called dui da or dui lian, were an important part of Chinese martial arts for centuries. Dui lian literally means, to train by a pair of combatants opposing each other – the character lian, means to practice; to train; to perfect one’s skill; to drill. As well, often one of these terms are also included in the name of fighting sets (shuang yan), “paired practice” (zheng sheng), “to struggle with strength for victory” (di), match – the character suggests to strike an enemy; and “to break” (po).

Generally there are 21, 18, 12, 9 or 5 drills or ‘exchanges/groupings’ of attacks and counterattacks, in each dui lian set. These drills were considered only generic patterns and never meant to be considered inflexible ‘tricks’. Students practiced smaller parts/exchanges, individually with opponents switching sides in a continuous flow. Basically, dui lian were not only a sophisticated and effective methods of passing on the fighting knowledge of the older generation, they were important and effective training methods. The relationship between single sets and contact sets is complicated, in that some skills cannot be developed with single sets, and, conversely, with dui lian. Unfortunately, it appears that most traditional combat oriented dui lian and their training methodology have disappeared, especially those concerning weapons. There are a number of reasons for this. In modern Chinese martial arts most of the dui lian are recent inventions designed for light props resembling weapons, with safety and drama in mind. The role of this kind of training has degenerated to the point of being useless in a practical sense, and, at best, is just performance.

By the early Song period, sets were not so much “individual isolated technique strung together” but rather were composed of techniques and counter technique groupings. It is quite clear that “sets” and “fighting (2 person) sets” have been instrumental in TCM for many hundreds of years – even before the Song Dynasty. There are images of two person weapon training in Chinese stone painting going back at least to the Eastern Han Dynasty.

According to what has been passed on by the older generations, the approximate ratio of contact sets to single sets was approximately 1:3. In other words, about 30% of the sets practiced at Shaolin were contact sets, dui lian, and two person drill training. This is, in part, evidenced by the Qing Dynasty mural at Shaolin.

Ancient literature from the Tang and Northern Song Dynasties suggests that some sets, including those that required two or more participants, became very elaborate and mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire new category of martial arts known as “fancy patterns for developing military skill” (Hua Fa Wuyi). During the Northern Song period it was noted by historians that this phenomenon had a negative influence on training in the military.

For most of its history, Shaolin martial arts was largely weapon-focused: staves were used to defend the monastery, not bare hands. Even the more recent military exploits of Shaolin during the Ming and Qing Dynasties involved weapons. According to some traditions, monks first studied basics for one year and were then taught staff fighting so that they could protect the monastery. Although wrestling has been as sport in China for centuries, weapons have been the most important part of Chinese wushu since ancient times. If one wants to talk about recent or ‘modern’ developments in Chinese martial arts (including Shaolin for that matter), it is the over-emphasis on bare hand fighting. During the Northern Song Dynasty (976-997 A.D) when platform fighting known as Da Laitai (Title Fights Challenge on Platform) first appeared, these fights were with only swords and staves. Although later, when bare hand fights appeared as well, it was the weapons events that became the most famous. These open-ring competitions had regulations and were organized by government organizations; some were also organized by the public. The government competitions resulted in appointments to military posts for winners and were held in the capital as well as in the prefectures.

Luc Paquin

In 2006, Dr. Donald Meeks was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

Dr. Donald Meeks dedicated his life to helping people with addictions, building a distinguished reputation as a Professor at the University of Toronto and the Associate Director of the Clinical Institute at the Centre for Mental Health and Addiction (CAMH). His work took him around the world as a special consultant to the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

In 2006, he was awarded one of the country’s highest distinctions – the Order of Canada – for his outstanding contribution to the Addiction field in Canada. No one could have predicted that just two short years after this high point, Don would experience two strokes that would forever change his life.

After the second stroke, Don was left with lingering weakness on his right side, permanent damage to his memory, and aphasia.

For an academic man who had built his career on his ability to read, write and express himself verbally, aphasia was an unexpected blow. “I suffered the most from a lack of self confidence in pubic situations – I feared that I would be inarticulate or lose my train of thought,” says Don. “Being referred to the Aphasia Institute was a ‘stroke of luck’!”

Don and his wife Sherril entered the Aphaisa Institute’s Introductory Program with great hope… and the program delivered. Don’s confidence began to build and Sherril connected with fellow caregivers and built a network of support for herself. Together, they learned about aphasia and some of the supportive communication techniques.

Don quickly graduated to the Aphasia Institute’s Toastmasters Club, where he continues today. Sherril remains connected to the Family group. Both are looking ahead with optimism although they appreciate that the journey has been very different for each of them.

Looking back, there’s an irony to having spent decades helping others only to find themselves, as Don refers to it, ‘on the other side of the gurney’.

Both know that the Aphasia Institute will be a key part of their lives for some time to come. “This is a best practice demonstration of everything I taught for years,” says Don. “The community at AI is astounding – we feel so welcomed and very much a part of this wonderful, wonderful community.”

Dr. Donald Meeks

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Forms

Forms or taolu (Pinyin: tàolù) in Chinese are series of predetermined movements combined so they can be practiced as a continuous set of movements. Forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a particular style branch, and were often taught to advanced students selected for that purpose. Forms contained both literal, representative and exercise-oriented forms of applicable techniques that students could extract, test, and train in through sparring sessions.

Today, many consider forms to be one of the most important practices in Chinese martial arts. Traditionally, they played a smaller role in training for combat application, and took a back seat to sparring, drilling and conditioning. Forms gradually build up a practitioner’s flexibility, internal and external strength, speed and stamina, and they teach balance and coordination. Many styles contain forms that use weapons of various lengths and types, using one or two hands. Some styles focus on a certain type of weapon. Forms are meant to be both practical, usable, and applicable as well as to promote fluid motion, meditation, flexibility, balance, and coordination. Teachers are often heard to say “train your form as if you were sparring and spar as if it were a form.”

There are two general types of forms in Chinese martial arts. Most common are solo forms performed by a single student. There are also sparring forms – choreographed fighting sets performed by two or more people. Sparring forms were designed both to acquaint beginning fighters with basic measures and concepts of combat, and to serve as performance pieces for the school. Weapons-based sparring forms are especially useful for teaching students the extension, range, and technique required to manage a weapon.

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

The term taolu is a shorten version of Tao Lu Yun Dong, an expression introduced only recently with the popularity of modern wushu. This expression refers to “exercise sets” and is used in the context of athletics or sport.

In contrast, in traditional Chinese martial arts alternative terminologies for the training of “sets or forms” are:

- Lian Quan Tao – Practicing sequence of fist

- Lian Quan Jiao – Practicing fists and feet

- Lian Bing Qi – Practicing weapons

- Dui Da and Dui Lian – Fighting sets

Luc Paquin

A charm bag is simply a magic spell inside a bag. They are spells in a bag and the most popular way of carrying power items with you.

To make a charm bag, simply fill with one or more magically charged items. Magically charged items may include herbs, stones, charms, drops of essential or magic oils, amulets and crystals.

Charm bags may be as simple as a square of fabric tied together or they may be beautifully embroidered hand made works of art. They may be made of silk, leather, metal or any fabric. The choice is yours, but keep in mind that the container is part of the spell.

Bag Colours

- Gold: Wealth, protection and the God

- Silver: Prosperity, the Moon, psychic and the Goddess

- Yellow: Healing, and finding employment

- Orange: Communication, messages and travel

- Green: Prosperity, abundance, friendship, growth and nature

- Blue: Peace, calm, wisdom and benevolence

- Purple: Wisdom, mysteries, wealth, grandeur and justice

- Red: Success, strength, romance and protection

- Pink: Love, friendship and healing

- Brown: Houses, home, justice, Earth and permanence

- Black: Absorbs and dissolves baneful energy

Bags with drawstring closures are useful because you can open and close them, adding materials as they are found or needed. A closed bag is called a “hand”.

Here are a few examples of stones that you could place in your bag:

- Aluminum: Travel and communication

- Amethyst: Wisdom and psychic powers

- Aventurine: Healing and prosperity.

- Clear Quartz: Good for any purpose

- Copper: Love and healing

- Gold: Prosperity and protection

- Iron: Protection and strength

- Moonstone: Emotions, peace and love

- Rose Quartz: Love and harmony

- Silver: Protection, Lunar power, love and prosperity

- Tiger’s Eye: Wealth and protection

- Tin: Wealth and honour

Here are a few examples of charms that you could place in your bag:

- Acorn: Luck, prosperity,protection from lightning, and sexual potency

- Broom: Brushes away negative influences, sweeps in luck, protection, wealth and good into the home

- Clover: Life, luck and abundance

- Hammer: Luck and a means of driving out evil

- Horn: Repel the”evil eye”, a symbol of nature and fertility and sexuality

- Horseshoe: Luck

- Key: Power, luck which lock it opens, hidden things

- Lightning-Struck Wood: Protection against all harm

- Pine Cone: Luck, favourable influences,protection from harm, sexual power, repels baneful influences

- Religious Symbol: Symbols of various religions are held to be protective

- Salt: Purification, repels evil and attracts wealth

- Silver: Protection, wealth and the blessing of all Goddesses

- Toadstone: Heal illnesses and to repel evil and is a fossilized shark’s tooth

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Weapons Training

Most Chinese styles also make use of training in the broad arsenal of Chinese weapons for conditioning the body as well as coordination and strategy drills. Weapons training (qìxiè) are generally carried out after the student is proficient in the basics, forms and applications training. The basic theory for weapons training is to consider the weapon as an extension of the body. It has the same requirements for footwork and body coordination as the basics. The process of weapon training proceeds with forms, forms with partners and then applications. Most systems have training methods for each of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu (shíbabanbingqì) in addition to specialized instruments specific to the system.

Application

Application refers to the practical use of combative techniques. Chinese martial arts techniques are ideally based on efficiency and effectiveness. Application includes non-compliant drills, such as Pushing Hands in many internal martial arts, and sparring, which occurs within a variety of contact levels and rule sets.

When and how applications are taught varies from style to style. Today, many styles begin to teach new students by focusing on exercises in which each student knows a prescribed range of combat and technique to drill on. These drills are often semi-compliant, meaning one student does not offer active resistance to a technique, in order to allow its demonstrative, clean execution. In more resisting drills, fewer rules apply, and students practice how to react and respond. ‘Sparring’ refers to the most important aspect of application training, which simulates a combat situation while including rules that reduce the chance of serious injury.

Competitive sparring disciplines include Chinese kickboxing Sanshou and Chinese folk wrestling Shuaijiao, which were traditionally contested on a raised platform arena Lèitái. Lèitái represents public challenge matches that first appeared in the Song Dynasty. The objective for those contests was to knock the opponent from a raised platform by any means necessary. San Shou represents the modern development of Lei Tai contests, but with rules in place to reduce the chance of serious injury. Many Chinese martial art schools teach or work within the rule sets of Sanshou, working to incorporate the movements, characteristics, and theory of their style. Chinese martial artists also compete in non-Chinese or mixed Combat sport, including boxing, kickboxing and Mixed martial arts.

Luc Paquin

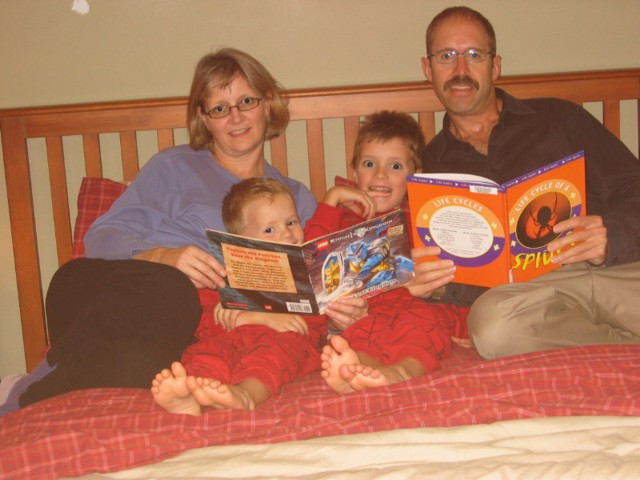

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys.

The Ardiel family piles into their big bed for a favourite nightly ritual. Jane reads a storybook aloud to her boys and husband while running her index finger along the page under the words so six-year old Ben can follow along. Sometimes Ben reads a page. Aiden, at four-years old is too young to read so he snuggles in to enjoy the tale. For dad Scott, although reading a sentence aloud is a struggle, he participates as fully as he can in this bonding family routine.

Most of us take for granted being able to read a bedtime story to our children. But for Scott, who acquired aphasia after a stroke in 2008, he lives with the challenge of trying to communicate and parent his boys. “[Aphasia] , that’s been a struggle from the beginning. [I] can’t tell [the boys how to do things], but I have to show them,” says Scott.

Even though Scott knows what he wants to say, he has difficulty expressing it. Sometimes he finds it hard to understand what others are saying and reading can be difficult. Scott and Jane found the Aphasia Institute to be a “nugget of hope” once Scott was released from rehab after his stroke. They found comfort in an environment that understood the impact aphasia had on the whole family.

Jane joined the Family Support and Education Group and found a community that empathized with her experience.

Today Scott is a member of the Toastmaster Aphasia Gavel Club and an active volunteer at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. Jane has made it her mission to educate every medical professional they have encountered along this journey about aphasia.

“Much of my own healing through this experience has come from the opportunity to help others. There’s a saying – we achieve happiness when we seek the happiness and wellbeing of others,” says Jane.

Jane & Scott Ardiel

Norma

Chinese Martial Arts

Training

Chinese martial arts training consists of the following components: basics, forms, applications and weapons; different styles place varying emphasis on each component. In addition, philosophy, ethics and even medical practice are highly regarded by most Chinese martial arts. A complete training system should also provide insight into Chinese attitudes and culture.

Basics

The Basics are a vital part of any martial training, as a student cannot progress to the more advanced stages without them. Basics are usually made up of rudimentary techniques, conditioning exercises, including stances. Basic training may involve simple movements that are performed repeatedly; other examples of basic training are stretching, meditation, striking, throwing, or jumping. Without strong and flexible muscles, management of Qi or breath, and proper body mechanics, it is impossible for a student to progress in the Chinese martial arts. A common saying concerning basic training in Chinese martial arts is as follows:

Train Both Internal and External

External training includes the hands, the eyes, the body and stances. Internal training includes the heart, the spirit, the mind, breathing and strength.

Stances

Stances (steps) are structural postures employed in Chinese martial arts training. They represent the foundation and the form of a fighter’s base. Each style has different names and variations for each stance. Stances may be differentiated by foot position, weight distribution, body alignment, etc. Stance training can be practiced statically, the goal of which is to maintain the structure of the stance through a set time period, or dynamically, in which case a series of movements is performed repeatedly. The Horse stance (qí ma bù/ma bù) and the bow stance are examples of stances found in many styles of Chinese martial arts.

Meditation

In many Chinese martial arts, meditation is considered to be an important component of basic training. Meditation can be used to develop focus, mental clarity and can act as a basis for qigong training.

Use of Qi

The concept of qi or ch’i is encountered in a number of Chinese martial arts. Qi is variously defined as an inner energy or “life force” that is said to animate living beings; as a term for proper skeletal alignment and efficient use of musculature (sometimes also known as fa jin or jin); or as a shorthand for concepts that the martial arts student might not yet be ready to understand in full. These meanings are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The existence of qi as a measurable form of energy as discussed in traditional Chinese medicine has no basis in the scientific understanding of physics, medicine, biology or human physiology.

There are many ideas regarding the control of one’s qi energy to such an extent that it can be used for healing oneself or others. Some styles believe in focusing qi into a single point when attacking and aim at specific areas of the human body. Such techniques are known as dim mak and have principles that are similar to acupressure.

Luc Paquin

Sealing wax is a wax material of a seal which, after melting, hardens quickly (to paper, parchment, ribbons and wire, and other material) forming a bond that is difficult to separate without noticeable tampering. Wax is used to verify something such as a document is unopened, to verify the sender’s identity, for example with a signet ring, and as decoration. Sealing wax can be used to take impressions of other seals. Wax was used to seal letters close and later, from about the 16th century, envelopes. Before sealing wax, the Romans used bitumen for this purpose.

Composition

Formulas vary, but there was a major shift after European trade with the Indies opened. In the Middle Ages sealing wax was typically made of beeswax and ‘Venice turpentine’, a greenish-yellow resinous extract of the European Larch tree. The earliest such wax was uncolored; later the wax was colored red with vermilion. From the 16th century it was compounded of various proportions of shellac, turpentine, resin, chalk or plaster, and coloring matter (often vermilion, or red lead), but not necessarily beeswax. The proportion of chalk varied; coarser grades are used to seal wine bottles and fruit preserves, finer grades for documents. In some situations, such as large seals on public documents, beeswax was used. On occasion, sealing wax has historically been perfumed by ambergris, musk and other scents.

By 1866 many colors were available: gold (using mica), blue (using smalt or verditer), black (using lamp black), white (using lead white), yellow (using the mercuric mineral turpeth, also known as Schuetteite), green (using verdigris) and so on. Some users, such as the British Crown, assigned different colors to different types of documents. Today a range of synthetic colors is available.

Method of Application

Sealing wax is available in the form of sticks, sometimes with a wick, or as granules. The stick is melted at one end (but not ignited or blackened), or the granules heated in a spoon, normally using a flame, and then placed where required, usually on the flap of an envelope. While the wax is still soft, the seal (preferably at the same temperature as the wax, for the best impression) should be quickly and firmly pressed into it and released.

Modern Use

The modern day has brought sealing wax to a new level of use and application. Traditional sealing wax candles are produced in Canada, France and Scotland, with formulations similar to those used historically.

Since the advent of a postal system, the use of sealing wax has become more for ceremony than security. Modern times have required new styles of wax, allowing for mailing of the seal without damage or removal. These new waxes are flexible for mailing and are referred to as glue-gun sealing wax, faux sealing wax and flexible sealing wax.

Wiccan

Seal your spells, parchments, petitions, letters, and more with this elegant Wicca Triquetra & Pagan Pentacle Sealing Wax! This sealing wax kit comes with one stick of natural, purple sealing wax and a metal seal, which has been engraved with the Wiccan symbol of the Triquetra & Pentacle. This makes a great gift for Witches, Pagans, Heathens, Celts and friends.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Chinese Martial Arts

Styles

China has a long history of martial arts traditions that includes hundreds of different styles. Over the past two thousand years many distinctive styles have been developed, each with its own set of techniques and ideas. There are also common themes to the different styles, which are often classified by “families” (jia), “sects” (pai) or “schools” (men). There are styles that mimic movements from animals and others that gather inspiration from various Chinese philosophies, myths and legends. Some styles put most of their focus into the harnessing of qi, while others concentrate on competition.

Chinese martial arts can be split into various categories to differentiate them: For example, external and internal. Chinese martial arts can also be categorized by location, as in northern and southern as well, referring to what part of China the styles originated from, separated by the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang); Chinese martial arts may even be classified according to their province or city. The main perceived difference between northern and southern styles is that the northern styles tend to emphasize fast and powerful kicks, high jumps and generally fluid and rapid movement, while the southern styles focus more on strong arm and hand techniques, and stable, immovable stances and fast footwork. Examples of the northern styles include changquan and xingyiquan. Examples of the southern styles include Bak Mei, Wuzuquan, Choy Li Fut and Wing Chun. Chinese martial arts can also be divided according to religion, imitative-styles, and family styles such as Hung Gar. There are distinctive differences in the training between different groups of the Chinese martial arts regardless of the type of classification. However, few experienced martial artists make a clear distinction between internal and external styles, or subscribe to the idea of northern systems being predominantly kick-based and southern systems relying more heavily on upper-body techniques. Most styles contain both hard and soft elements, regardless of their internal nomenclature. Analyzing the difference in accordance with yin and yang principles, philosophers would assert that the absence of either one would render the practitioner’s skills unbalanced or deficient, as yin and yang alone are each only half of a whole. If such differences did once exist, they have since been blurred.

Luc Paquin

When people lose their ability to communicate due to brain damage caused by stroke or trauma, as persons with aphasia do, there is a good news and a bad news. The good news is that often not all is lost. Depending on the extensiveness of the damage, parts of the brain that used to be involved in speaking or understanding language may still be functioning. Speech therapies aim to induce these preserved areas to reorganize and regain their ability to produce and process speech. The not so good news is that such reorganization takes a long time, especially in older individuals.

Many people are familiar with traditional speech therapies that employ exercises to help persons with aphasia re-learn how to use language to communicate with their families and friends. Depending on the size and the location of brain damage, speech therapies can take years and improvement is usually slow. However, scientists are now looking into a newer type of treatment that combines traditional speech therapy with a weak electrical stimulation of the brain that might speed up recovery from aphasia. The method is called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and is applied non-invasively, by placing an electrode on top of the skull.

When people hear about electrical stimulation used to treat brain disorders, many conjure up an image from the 1975 movie “One flew over the cuckoo’s nest” which featured scenes of painful electroconvulsive therapy. This type of intervention, which in reality is painless, is still applied as a last resort to alleviate treatment-resistent depression and involves much stronger electrical currents than tDCS, which uses electrical current equivalent roughly to a 9V battery. The PBS Newshour video below describes the principles behind tDCS and how it could be applied for purposes like focusing the mind and keeping it alert.

The idea behind using tDCS in Aphasia therapy is that the small amount of current applied to the brain may enhance plasticity and prime the brain to learn faster. The approach would be to employ tDCS in combination with traditional clinical therapies rather than as a substitution.

There are many parts of the brain that are involved in understanding or producing speech and those parts are intricately connected into complex networks. Information flows between the various parts of the speech and language networks along cables called axons. Such information flow is important for the brain to access vocabulary and grammar rules, assemble words into sentences and send commands to the mouth and the tongue to produce speech. When stroke or trauma damages the areas that are part of this language network, the information flow is disturbed or cut off and people experience communication deficits. New connections need to be established between the preserved brain areas in order to regain one’s ability to speak.

The weak electrical currents of tDCS might stimulate the brain to form these new connections faster than it would with traditional speech therapy alone. But how exactly that would happen and what biological changes in the brain accompany the behavioral modulations observed in the video above is still unclear.

At present, tDCS as applied to aphasia is still considered experimental treatment and health insurance would not cover the cost of therapy. Data on tDCS efficacy for treating aphasia are still scarce. Most studies are conducted with small number of patients, limited language tasks, and short follow-up periods. However, at least some of the studies seem to suggest that tDCS has potential to improve aphasia rehabilitation.

Multiple centers in the United States, Canada, and Europe are in the process of conducting more rigorous clinical trials and may have more evidence soon whether tDCS works for aphasia. Those interested in enrolling in such studies can go to ClinicalTrials.gov to find out more information.

As methods improve and more data become available, tDCS may prove to be a great tool that will boost recovery from aphasia, which for the moment is still a long and arduous journey.

Norma