Joseph A. Adler

Diagram of the Supreme Polarity (Taiji tu)

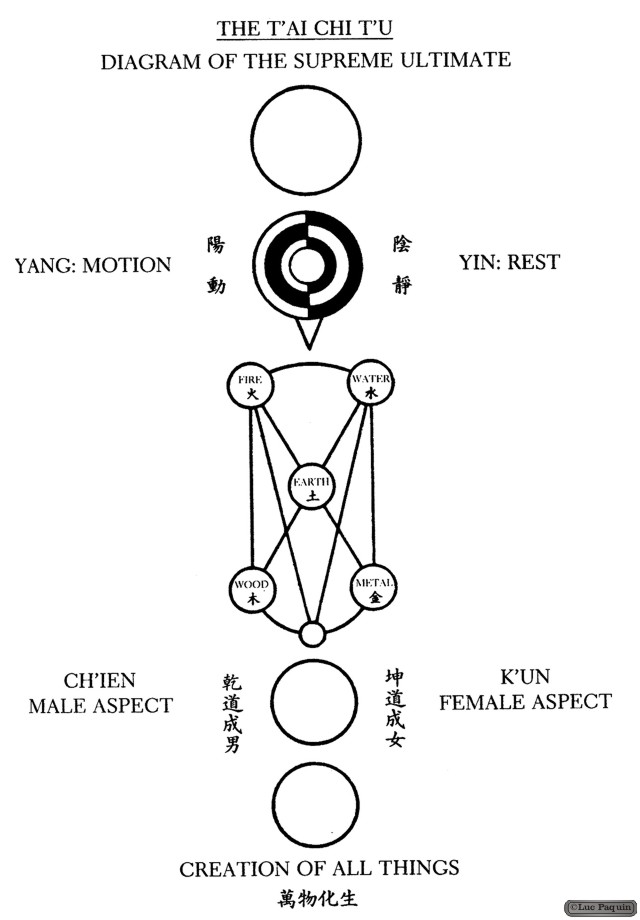

Zhou’s best-known contribution to the Neo-Confucian tradition was his brief “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” and the Diagram itself. The text has engendered controversy and debate ever since the twelfth century, when Zhu Xi and Lü Zuqian (1137-1181) placed it at the head of their Neo-Confucian anthology, Reflections on Things at Hand (Jinsilu), in 1175. It was controversial from a sectarian Confucian standpoint because the diagram explained by the text was attributed to a prominent Daoist master, Chen Tuan (Chen Xiyi, 906-989), and because the key terms of the text had well-known Daoist origins. Scholars to the present day have attempted to interpret what Zhou Dunyi meant by them.

The two key terms, which appear in the opening line of the Explanation, are wuji and taiji, translated here as “Non-Polar” and “Supreme Polarity.” Wuji had been used in the classical Daoist texts, Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Liezi. Wu is a negation, roughly equivalent to “there is not;” ji is literally the ridgepole of a peaked roof, and usually means “limit” or “ultimate.” So in these early texts wuji means “the unlimited,” or “the infinite.” But in later Daoist texts it came to denote a state of primordial chaos, prior to the differentiation of yin and yang, and sometimes equivalent to dao.

Taiji was found in several classical texts, mostly but not exclusively Daoist. For the Song Neo-Confucians, the locus classicus of taiji was the Appended Remarks (Xici), or Great Treatise (Dazhuan), one of the appendices of the Classic of Change (Yijing): “In change there is the Supreme Polarity, which generates the Two Modes [yin and yang]”. Taiji here is a generative principle of bipolarity.

But the term was much more prominent and nuanced in Daoism than in Confucianism. Taiji was the name of one of the Daoist heavens, and thus was prefixed to the names of many Daoist immortals, or divinities, and to the titles of the texts attributed to them. It was sometimes identified with Taiyi, the Supreme One (a Daoist divinity), and with the pole star of the Northern Dipper. It carried connotations of a turning point in a cycle, an end point before a reversal, and a pivot between bipolar processes. It became a standard part of Daoist cosmogonic schemes, where it usually denoted a stage of chaos later than wuji, a stage or state in which yin and yang have differentiated but have not yet become manifest. It thus represented a “complex unity,” or the unity of potential multiplicity. In the form of Daoist meditation known as neidan, or physiological alchemy, it represented the energetic potential to reverse the normal process of aging by cultivating within one’s body the spark of the primordial qi (psycho-physical substance), thereby “returning” to the primordial, creative state of chaos from which the cosmos evolved. Chen Tuan’s Taiji Diagram, when read from the bottom upwards, is thought to have been originally a schematic representation of this process of “returning to wuji”, the “Non-Polar,” undifferentiated state.

Zhou Dunyi ignored the bottom-up reading of the Diagram, leaving one or two of its elements unexplained. Focusing on the top-down differentiation of the cosmos from the primordial unity to the “myriad things,” he departed from a Daoist interpretation by singling out the human being as the highest manifestation of cosmic creativity, thereby giving the Diagram a distinctly Confucian meaning. The enigmatic opening line of his Explanation suggests that the Supreme Polarity, the ultimate principle of differentiation, is itself fundamentally undifferentiated (this is stated explicitly a few sentences later). Similarly, activity and stillness, the first manifestations of polarity, each contains the seed of its opposite.

In bringing this largely Daoist terminology into Confucian discourse (chaos was generally frowned upon by Confucians), Zhou may have been attempting to show that the Confucian view of humanity’s role in the cosmos was not really opposed to the fundamentals of the Daoist worldview, in which human categories and values were thought to alienate human beings from the Dao. In effect, he was co-opting Daoist terminology to show that the Confucian worldview was actually more inclusive than the Daoist: it could accept a primordial chaos while still affirming the reality of the differentiated, phenomenal world. For Zhu Xi and his school, the most important contribution of this text was its integration of metaphysics (taiji, which Zhu equated with li, the ultimate natural/moral order) and cosmology (yin-yang and Five Phases).

Luc Paquin

Mentha pulegium, commonly (European) pennyroyal, also called squaw mint, mosquito plant and pudding grass, is a species of flowering plant in the family Lamiaceae native to Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Crushed pennyroyal leaves exhibit a very strong fragrance similar to spearmint. Pennyroyal is a traditional culinary herb, folk remedy, and abortifacient. The essential oil of pennyroyal is used in aromatherapy, and is also high in pulegone, a highly toxic volatile organic compound affecting liver and uterine function.

Culinary and Medicinal Uses

Pennyroyal was commonly used as a cooking herb by the Greeks and Romans. The ancient Greeks often flavored their wine with pennyroyal. A large number of the recipes in the Roman cookbook of Apicius call for the use of pennyroyal, often along with such herbs as lovage, oregano and coriander. Although it was commonly used for cooking in the Middle Ages, it gradually fell out of use as a culinary herb and is seldom used as such today. The fresh or dried leaves of the plant were used to flavor pudding.

Even though pennyroyal oil is extremely poisonous, people have relied on the fresh and dried herb for centuries. Early settlers in colonial Virginia used dried pennyroyal to eradicate pests. Pennyroyal was such a popular herb that the Royal Society published an article on its use against rattlesnakes in the first volume of its Philosophical Transactions in 1665.

Pennyroyal is used to make herbal teas, which, although not proven to be dangerous to healthy adults in small doses, is not recommended, due to its known toxicity to the liver. Consumption can be fatal to infants and children. It has been traditionally employed as an emmenagogue (menstrual flow stimulant) or as an abortifacient. Pennyroyal is also used to settle an upset stomach and to relieve flatulence. The fresh or dried leaves of pennyroyal have also been used when treating colds, influenza, abdominal cramps, and to induce sweating, as well as in the treatment of diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis, and in promoting latent menstruation. Pennyroyal leaves, both fresh and dried, are especially noted for repelling insects. However, when treating infestations such as fleas, using the plant’s essential oil should be avoided due to its toxicity to both humans and animals, even at extremely low levels.

Wiccan

Pennyroyal is well known as a magical herb. In some traditions it’s associated with money, while in others Pennyroyal is connected to strength and protection. In Hoodoo and some forms of American folk magic, Pennyroyal is carried to ward off the “evil eye.” For some protection magic, make a sachet stuffed with Pennyroyal and tuck it in your purse. In a few traditions, Pennyroyal is associated with money magic. If you own a business, place a sprig over the door to draw in customers and prosperity. Try making a bar of Money Soap to wash your hands with, or use Pennyroyal to brew up some Prosperity Oil.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Joseph A. Adler

Zhou Dunyi (or Zhou Lianxi, 1017-1073) occupies a position in the Chinese tradition based on a role assigned to him by Zhu Xi (1130-1200), the architect of the Neo-Confucian school that eventually became “orthodox.” According to one version of the Succession to the Way (daotong) given by Zhu Xi, Zhou was the first true Confucian Sage since Mencius (4th c. BCE), and was a formative influence on Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi (Zhou’s nephews), from whom Zhu Xi drew significant parts of his system of thought and practice. Thus Zhou Dunyi came to be known as the “founding ancestor” of the Cheng-Zhu school, which dominated Chinese philosophy for over 700 years. His “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo), as interpreted by Zhu, became the accepted foundation of Neo-Confucian cosmology. Along with his other major work, Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu), it established the appendices to the Yijing as basic textual sources of the Neo-Confucian revival of the Song dynasty. And Zhou’s short essay, “On the Love of the Lotus” (Ai lian shuo), is still a regular part of the high school curriculum in Taiwan.

Zhou was born to a family of scholar-officials in Hunan province. After his father died when he was about fourteen, he was adopted by his maternal uncle, Zheng Xiang, through whom he later obtained his first government post. Despite the increasing importance of the civil service examination system in determining status in Song society, Zhou never obtained the “Presented Scholar” (jinshi) degree. Consequently, while he earned praise for his service in a very active official career, he never rose to a high position.

Zhou’s honorific name, Lianxi (“Lian Stream”), was the one he gave to his study, built in 1062 at the foot of Mt. Lu in Jiangxi province; it was named after a stream in Zhou’s home village. He was posthumously honored in 1200 as Yuangong (Duke of Yuan), and in 1241 was accorded sacrifices in the official Confucian temple.

During his lifetime, Zhou was not an influential figure in Song political or intellectual life. He had few, if any, formal students other than his nephews, the Cheng brothers, who studied with him only briefly when they were teenagers. He was most remembered by his contemporaries for the evident quality of his personality and mind. He was known as a warm, humane man who felt a deep kinship with the natural world, a man with penetrating insight into the Way of Heaven, the natural-moral order. To later Confucians he personified the virtue of “authenticity” (cheng), the full realization of the innate goodness and wisdom of human nature.

Zhou’s connection with the Cheng brothers was the ostensible rationale for his being considered the founder of the Cheng-Zhu school of Neo-Confucianism. Yet that connection was, in fact, slight. Although they later spoke fondly of their short time with him and were personally impressed with him (as were many other contemporaries), the Chengs did not acknowledge any specific philosophical debts to Zhou. Nor are any such debts evident in their teachings. In fact, Zhou’s teachings were rather suspect in the eyes of many Song Confucians because of his evident debts to Daoism. This was especially true during the Southern Song (1127-1279), when Confucians increasingly defined themselves in opposition to Buddhism and Daoism. Indeed, Zhou’s “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” attracted considerable interest among Daoists, and made its way into the Daoist Canon (Daozang).

Given Zhou’s tenuous connection with the Chengs, why then did Zhu Xi regard him as the first Sage of the Song? The question is significant, for had it not been for Zhu Xi’s estimation of him, Zhou’s writings would almost certainly not have become as central to the Neo-Confucian tradition as they are. They apparently were not widely known outside the circle of the Chengs and their students until the twelfth century, and today the only extant editions besides those edited by Zhu Xi are the Taijitu shuo in the Daoist Canon and the Tongshu in another anthology , neither of which is accompanied by a commentary. So it is safe to say that Zhou Dunyi’s place in the Chinese tradition is largely a creation of Zhu Xi.

It was the content of Zhou’s teachings in relation to Zhu Xi’s system of thought and practice that persuaded Zhu to exalt Zhou Dunyi, to ignore his Daoist connections, and to stretch the available data concerning Zhou’s affiliation with the Chengs.[6] Zhu was particularly interested in the relationship between the active, functioning mind (xin) and its metaphysical substance or nature (xing), and in the implications of that relationship for moral self-cultivation. Zhou’s writings supported Zhu’s position on these issues by integrating the metaphysical, psycho-physical, and ethical dimensions of the mind, chiefly by means of the concepts of “Supreme Polarity” (taiji), “authenticity” (cheng), and the interpenetration of activity (dong) and stillness (jing).

Translated below are the complete text of his best-known work, the “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity” (Taijitu shuo) and six of the forty short sections of Penetrating the Classic of Change (Tongshu). These works stand on their own as foundational texts of the Neo-Confucian tradition and as superb examples of the integration of Confucian ethics and Daoist naturalism.

Luc Paquin

Hodor might have aphasia but persons with aphasia are not “simple-minded”.

It is all over the news – Hodor has been diagnosed with expressive aphasia. If you belong to what seems to be a minority of people who don’t watch HBO’s Game of Thrones then you probably haven’t heard of Hodor, so here is how The Conversation describes him:

- Hodor is the brawny, simple-minded stableboy of the Stark family in Winterfell. His defining characteristic, of course, is that he only speaks a single word: “Hodor”.

No matter what the situation is, what is asked of him, or what is being said to him, it’s always – hodor, hodor, hodor. Which is how he got his aphasia diagnosis:

- Those who read the A Song of Ice and Fire book series by George R R Martin may know something that the TV fans don’t: his name isn’t actually Hodor. According to his great-grandmother Old Nan, his real name is Walder. “No one knew where ‘Hodor’ had come from,” she says, “but when he started saying it, they started calling him by it. It was the only word he had.”

- Whether he intended it or not, Martin created a character who is a textbook example of someone with a neurological condition called expressive aphasia.

Diagnosing with aphasia a popular character from a widely watched TV show (its 5th season premiere drew 8 million viewers) makes for a fun read and it is also a great way to spread awareness about this neurological disorder. Most people have never heard of aphasia despite that it is a fairly common condition that affects about a third of all stroke patients. Aphasia results from brain injury that damages areas that control speech and language. Such damage is most commonly caused by stroke or head trauma but it could also result from tissue degeneration.

Media attention that boosts aphasia awareness is welcome but there is a caveat. Many of the articles that diagnosed Hodor’s language peculiarity as aphasia introduced him as “simple-minded”. Other online depictions of Hodor also characterize him as “slow of wits”. This kind of allusions leave the impression that Hodor has intellectual deficits.

The articles about Hodor make for a fun and fascinating read about aphasia and the history of its discovery. But given the context, it would have been great if they emphasized that aphasia is a disorder that affects speech and language only. It does not affect people’s intellectual capabilities.

Inability to express oneself, speaking with grammatically incorrect sentences, inserting words that make no logical sense, and difficulty understanding what is being said are all characteristics of various forms of aphasia. Unfortunately, they are also associated with intellectual deficits. This is a problem with which many persons with aphasia struggle because people who are unfamiliar with the disorder assume that patients with aphasia have intellectual deficits as well. Which is why it is important to make the distinction clear.

Norma

Martial Arts – Tai Chi – Taiji

Core Concept

Taiji is understood to be the highest conceivable principle, that from which existence flows. This is very similar to the Daoist idea “reversal is the movement of the Dao”. The “supreme ultimate” creates yang and yin: movement generates yang; when its activity reaches its limit, it becomes tranquil. Through tranquility the supreme ultimate generates yin. When tranquility has reached its limit, there is a return to movement. Movement and tranquility, in alternation, become each the source of the other. The distinction between the yin and yang is determined and the two forms (that is, the yin and yang) stand revealed. By the transformations of the yang and the union of the yin, the 5 elements (Qi) of water, fire, wood, metal and earth are produced. These 5 Qi become diffused, which creates harmony. Once there is harmony the 4 seasons can occur. Yin and yang produced all things, and these in their turn produce and reproduce, this makes these processes never ending. Taiji underlies the practical Taijiquan (T’ai Chi Ch’uan) – A Chinese internal martial art based on the principles of Yin and Yang and Taoist philosophy, and devoted to internal energetic and physical training. Taijiquan is represented by five family styles: Chen, Sun, Yang, Wu(Hao), and Wu.

Luc Paquin

Patchouli (Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth; also patchouly or pachouli) is a species of plant from the genus Pogostemon. It is a bushy herb of the mint family, with erect stems, reaching two or three feet (about 0.75 metre) in height and bearing small, pale pink-white flowers. The plant is native to tropical regions of Asia, and is now extensively cultivated in China, Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Mauritius, Taiwan, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Perfume

The heavy and strong scent of patchouli has been used for centuries in perfumes and, more recently, in incense, insect repellents, and alternative medicines. The word derives from the Tamil patchai (green), ellai (leaf). In Assamese it is known as xukloti.

Pogostemon cablin, P. commosum, P. hortensis, P. heyneasus and P. plectranthoides are all cultivated for their essential oil, known as patchouli oil.

Extraction of Essential Oil

Extraction of patchouli’s essential oil is by steam distillation of the leaves, requiring rupture of its cell walls by steam scalding, light fermentation, or drying.

Leaves may be harvested several times a year and, when dried, may be exported for distillation. Some sources claim a highest quality oil is usually produced from fresh leaves distilled close to where they are harvested; others that baling the dried leaves and fermenting them for a period of time is best.

Uses

Perfume

Patchouli is used widely in modern perfumery, by individuals who create their own scents, and in modern scented industrial products such as paper towels, laundry detergents, and air fresheners. Two important components of its essential oil are patchoulol and norpatchoulenol.

Insect Repellent

One study suggests that patchouli oil may serve as an all-purpose insect repellent. More specifically, the patchouli plant is claimed to be a potent repellent against the Formosan subterranean termite.

During the 18th and 19th century, silk traders from China traveling to the Middle East packed their silk cloth with dried patchouli leaves to prevent moths from laying their eggs on the cloth. It has also been proven to effectively prevent female moths from adhering to males, and vice versa. Many historians speculate that this association with opulent Eastern goods is why patchouli was considered by Europeans of that era to be a luxurious scent. It is said that patchouli was used in the linen chests of Queen Victoria in this way.

Incense

Patchouli is an important ingredient in East Asian incense. Both patchouli oil and incense underwent a surge in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s in the US and Europe, mainly as a result of the hippie movement of those decades.

Culinary

Patchouli leaves have been used to make an herbal tea. In some cultures, Patchouli leaves are eaten as a vegetable.

Wiccan

Patchouli is a popular herb found in many modern Pagan rituals. Its exotic scent brings to mind far-off, magical places, and it’s often used in incense blends, potpourri, and ritual workings. Associated with love, wealth, and sexual power, patchouli can be used in a variety of magical workings. Place patchouli leaves in a sachet, and carry it in your pocket or wear around your neck. In some traditions of hoodoo and folk magic, a dollar sign is inscribed on a piece of paper using patchouli oil. The paper is then carried in your wallet, and this should draw money your way. There are some traditions of modern magic in which patchouli is valued for its repelling power.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Martial Arts – Tai Chi – Taiji

Taiji is a Chinese cosmological term for the “Supreme Ultimate” state of undifferentiated absolute and infinite potential, the oneness before duality, from which Yin and Yang originate, contrasted with the Wuji (“Without Ultimate”).

The term Taiji and its other spelling T’ai chi (using Wade-Giles as opposed to Pinyin) are most commonly used in the West to refer to Taijiquan (or T’ai chi ch’uan), an internal martial art, Chinese meditation system and health practice. This article, however, refers only to the use of the term in Chinese philosophy and Taoist spirituality.

Taiji in Chinese Texts

Taiji references are found in Chinese classic texts associated with many schools of Chinese philosophy.

Zhang and Ryden explain the ontological necessity of Taiji.

- Any philosophy that asserts two elements such as the yin-yang of Chinese philosophy will also look for a term to reconcile the two, to ensure that both belong to the same sphere of discourse. The term ‘supreme ultimate’ performs this role in the philosophy of the Book of Changes. In the Song dynasty it became a metaphysical term on a par with the Way.

Zhuangzi

The Daoist classic Zhuangzi introduced the Taiji concept. One of the (ca. 3rd century BCE) “Inner Chapters” contrasts Taiji “great ultimate” (“zenith”) and Liuji “six ultimates; six cardinal directions” (“nadir”).

- The Way has attributes and evidence, but it has no action and no form. It may be transmitted but cannot be received. It may be apprehended but cannot be seen. From the root, from the stock, before there was heaven or earth, for all eternity truly has it existed. It inspirits demons and gods, gives birth to heaven and earth. It lies above the zenith but is not high; it lies beneath the nadir but is not deep. It is prior to heaven and earth, but is not ancient; it is senior to high antiquity, but it is not old.

Huainanzi

The (2nd century BCE) Huainanzi mentions Taiji in a context of a Daoist Zhenren “true person; perfected person” who perceives from a “Supreme Ultimate” that transcends categories like yin and yang.

- The fu-sui (burning mirror) gathers fire energy from the sun; the fang-chu (moon mirror) gathers dew from the moon. What are [contained] between Heaven and Earth, even an expert calculator cannot compute their number. Thus, though the hand can handle and examine extremely small things, it cannot lay hold of the brightness [of the sun and moon]. Were it within the grasp of one’s hand (within one’s power) to gather [things within] one category from the Supreme Ultimate (t’ai-chi) above, one could immediately produce both fire and water. This is because Yin and Yang share a common ch’i and move each other.

I Ching

Taiji also appears in the Xìcí “Appended Judgments” commentary to the I Ching, a late section traditionally attributed to Confucius but more likely dating to about the 3rd century B.C.E.

- Therefore there is in the Changes the Great Primal Beginning. This generates the two primary forces. The two primary forces generate the four images. The four images generate the eight trigrams. The eight trigrams determine good fortune and misfortune. Good fortune and misfortune create the great field of action.

This two-squared generative sequence includes Taiji -> Yin and Yang (two polarities) -> Sixiang (Four Symbols) -> Bagua (eight trigrams).

Richard Wilhelm and Cary F. Baynes explain.

- The fundamental postulate is the “great primal beginning” of all that exists, t’ai chi – in its original meaning, the “ridgepole”. Later Indian philosophers devoted much thought to this idea of a primal beginning. A still earlier beginning, wu chi, was represented by the symbol of a circle. Under this conception, t’ai chi was represented by the circle divided into the light and the dark, yang and yin, Yin yang.svg. This symbol has also played a significant part in India and Europe. However, speculations of a Gnostic-dualistic character are foreign to the original thought of the I Ching; what it posits is simply the ridgepole, the line. With this line, which in itself represents oneness, duality comes into the world, for the line at the same time posits an above and a below, a right and left, front and back – in a word, the world of the opposites.

Taijitu Shuo

The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073 CE) wrote the Taijitu shuo “Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate”, which became the cornerstone of Neo-Confucianist cosmology. His brief text synthesized aspects of Chinese Buddhism and Daoism with metaphysical discussions in the I ching.

Zhou’s key terms Wuji and Taiji appear in the opening line, which Adler notes could also be translated “The Supreme Polarity that is Non-Polar!”.

- Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established. The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.

Instead of usual Taiji translations “Supreme Ultimate” or “Supreme Pole”, Adler uses “Supreme Polarity” (see Robinet 1990) because Zhu Xi describes it as the alternating principle of yin and yang, and …

- insists that taiji is not a thing (hence “Supreme Pole” will not do). Thus, for both Zhou and Zhu, taiji is the yin-yang principle of bipolarity, which is the most fundamental ordering principle, the cosmic “first principle.” Wuji as “non-polar” follows from this.

Luc Paquin

Many people are not familiar with aphasia or they might just not realize that someone has difficulty communicating because of aphasia.

Carrying an Aphasia ID is a great way to ease communication awkwardness. You can customize and print an ID card for free by following the link provided below. You can then present the card when buying groceries, paying for gas, meeting new people, or in any other situation when you think a person might need to be informed that you have aphasia.

Click on the link aphasia ID card to customize and print your own card for free.

A free online tool for people with aphasia.

Create a personalized Aphasia ID that you can print and start carrying right away. This is a great way to ease communication awkwardness, especially for people who are unfamiliar with aphasia.

Aphasia ID. Create a customized ID right at home.

- Luc

- Paquin

- Professional

- Date Issued: 8/2/2015

Make yours today!

I am a: Professional

Carry your ID to help people know about your challenges with communication. You can also make IDs for your friends who don’t have aphasia, so they can show their support.

Norma

Martial Arts – Tai Chi

T’ai Chi Ch’uan Today

In the last twenty years or so, t’ai chi ch’uan classes that purely emphasise health have become popular in hospitals, clinics, as well as community and senior centres. This has occurred as the baby boomers generation has aged and the art’s reputation as a low-stress training method for seniors has become better known.

As a result of this popularity, there has been some divergence between those that say they practice t’ai chi ch’uan primarily for self-defence, those that practice it for its aesthetic appeal, and those that are more interested in its benefits to physical and mental health. The wushu aspect is primarily for show; the forms taught for those purposes are designed to earn points in competition and are mostly unconcerned with either health maintenance or martial ability. More traditional stylists believe the two aspects of health and martial arts are equally necessary: the yin and yang of t’ai chi ch’uan. The t’ai chi ch’uan “family” schools, therefore, still present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students in studying the art.

Philosophy

The philosophy of t’ai chi ch’uan is that, if one uses hardness to resist violent force, then both sides are certainly to be injured at least to some degree. Such injury, according to t’ai chi ch’uan theory, is a natural consequence of meeting brute force with brute force. Instead, students are taught not to directly fight or resist an incoming force, but to meet it in softness and follow its motion while remaining in physical contact until the incoming force of attack exhausts itself or can be safely redirected, meeting yang with yin. When done correctly, this yin/yang or yang/yin balance in combat, or in a broader philosophical sense, is a primary goal of t’ai chi ch’uan training. Lao Tzu provided the archetype for this in the Tao Te Ching when he wrote, “The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong.”

Traditional schools also emphasize that one is expected to show wude (“martial virtue/heroism”), to protect the defenseless, and show mercy to one’s opponents.

Health

A 2011 overview of existing research on t’ai chi ch’uan’s health effects found evidence of medical benefit for preventing falls, mental health, and general health in elderly people. There wasn’t conclusive evidence for any of the other conditions researched, including Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer and arthritis.

The practice of t’ai chi ch’uan is encouraged by the National Parkinson Foundation and Diabetes Australia.

Luc Paquin

Mugwort is a common name for several species of aromatic plants in the genus Artemisia. In Europe, mugwort most often refers to the species Artemisia vulgaris, or common mugwort. While other species are sometimes referred to by more specific common names, they may be called simply “mugwort” in many contexts. For example, one species, Artemisia argyi, is often called “mugwort” in the context of traditional Asian medicine but may be also referred to by the more specific name “Chinese mugwort”.

Mugworts are used medicinally, especially in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean traditional medicine. Some mugworts have also found a use in modern medicine for their anti-herpetic effect. They are also used as an herb to flavor food. In Korea, mugworts were also used for plain, non-medicinal consumption; in South Korea, mugworts, called ssuk, are still used as a staple ingredient in many dishes including rice cakes and soup.

Medicinal

The mugwort plant contains essential oils (such as cineole, or wormwood oil, and thujone), flavonoids, triterpenes, and coumarin derivatives. It was also used as an anthelminthic, so it is sometimes confused with wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). The plant, called nagadamni in Sanskrit, is used in Ayurveda for cardiac complaints as well as feelings of unease, unwellness and general malaise.

In traditional Japanese, Korean and Chinese medicine, Chinese mugwort (Folium Artemisiae argyi) is used for moxibustion, for a wide variety of health issues. The herb can be placed directly on the skin, attached to acupuncture needles, or rolled into sticks and waved gently over the area to be treated. In all instances, the herb is ignited and releases heat. Not only is it the herb which is believed to have healing properties in this manner, but it is also the heat released from the herb in a precise area that heals. There is significant technique involved when the herb is rolled into tiny pieces the size of a rice grain and lit with an incense stick directly on the skin. The little herbal fire is extinguished just before the lit herb actually touches the skin.

In traditional Chinese medicine there is a belief that moxibustion of mugwort is effective at increasing the cephalic positioning of fetuses who were in a breech position before the intervention. A Cochrane review in 2012 found that moxibustion may be beneficial in reducing the need for ECV, but stressed a need for well-designed randomised controlled trials to evaluate this usage.

Medieval Europe

In the European Middle Ages, mugwort was used as a magical protective herb. Mugwort was used to repel insects, especially moths, from gardens. Mugwort has also been used from ancient times as a remedy against fatigue and to protect travelers against evil spirits and wild animals. Roman soldiers put mugwort in their sandals to protect their feet against fatigue. Mugwort is one of the nine herbs invoked in the pagan Anglo-Saxon Nine Herbs Charm, recorded in the 10th century in the Lacnunga.

Wiccan

Mugwort is an herb that is found fairly regularly in many modern Pagan magical practices. From its use as an incense, for smudging, or in spellwork, mugwort is a highly versatile – and easy to grow – herb. In some magical traditions, mugwort is associated with divination and dreaming. To bring about prophecy and divinatory success, make an incense of mugwort to burn at your workspace, or use it in smudge sticks around the area in which you are performing divination rituals.

The Lost Bearded White Brother