Anthroposophy

History

In 1912, the Anthroposophical Society was founded. After World War I, the Anthroposophical movement took on new directions. Projects such as schools, centers for those with special needs, organic farms and medical clinics were established, all inspired by anthroposophy.

In 1923, faced with differences between older members focusing on inner development and younger members eager to become active in the social transformations of the time, Steiner refounded the Society in an inclusive manner and established a School for Spiritual Science. As a spiritual basis for the refounded movement, Steiner wrote a “Foundation Stone Meditation” which remains a central meditative expression of anthroposophical ideas.

Steiner died just over a year later, in 1925. The Second World War temporarily hindered the anthroposophical movement in most of Continental Europe, as the Anthroposophical Society and most of its daughter movements (e.g. Steiner/Waldorf education) were banned by the National Socialists (Nazis); virtually no anthroposophists ever joined the National Socialist Party.

By 2007, national branches of the Anthroposophical Society had been established in fifty countries, and about 10,000 institutions around the world were working on the basis of anthroposophy. In the same year, the Anthroposophical Society was called the “most important esoteric society in European history”.

Central Ideas

Spiritual Knowledge and Freedom

Anthroposophical proponents aim to extend the clarity of the scientific method to phenomena of human soul-life and to spiritual experiences. This requires developing new faculties of objective spiritual perception, which Steiner maintained was possible for humanity today. The steps of this process of inner development he identified as consciously achieved imagination, inspiration and intuition. Steiner believed results of this form of spiritual research should be expressed in a way that can be understood and evaluated on the same basis as the results of natural science: “The anthroposophical schooling of thinking leads to the development of a non-sensory, or so-called supersensory consciousness, whereby the spiritual researcher brings the experiences of this realm into ideas, concepts, and expressive language in a form which people can understand who do not yet have the capacity to achieve the supersensory experiences necessary for individual research.”

Steiner hoped to form a spiritual movement that would free the individual from any external authority: “The most important problem of all human thinking is this: to comprehend the human being as a personality grounded in him or herself.” For Steiner, the human capacity for rational thought would allow individuals to comprehend spiritual research on their own and bypass the danger of dependency on an authority.

Steiner contrasted the anthroposophical approach with both conventional mysticism, which he considered lacking the clarity necessary for exact knowledge, and natural science, which he considered arbitrarily limited to investigating the outer world.

Luc Paquin

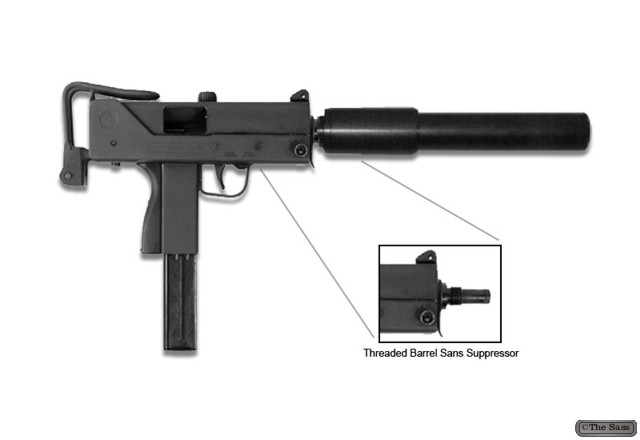

Ingram MAC-10

The MAC-10 (Military Armament Corporation Model 10, officially the M-10) is a compact, blowback operated machine pistol developed by Gordon B. Ingram in 1964. It is chambered in either .45 ACP or 9mm. A two-stage suppressor by Sionics, was designed for the MAC-10, which not only abated the noise created, but made it easier to control on full automatic.

Design

The M-10 was built predominantly from steel stampings. A notched cocking handle protrudes from the top of the receiver, and by turning the handle 90° would lock the bolt, and act as an indicator that the weapon is unable to fire. The M-10 has a telescoping bolt, which wraps around the barrel. This allows a more compact weapon, and balances the weight of the weapon over the pistol grip where the magazine is located. The M-10 fires from an open bolt, and the light weight of the bolt results in a rapid rate of fire. In addition, this design incorporates a built in feed ramp as part of the trigger guard (a new concept at the time) and to save on cost the magazine was recycled from the M3 Grease Gun. The barrel is threaded to accept a suppressor, which worked by reducing the discharge’s sound, without attempting to reduce the velocity of the bullet. At the suggestion of the United States Army, it also acted as a foregrip to inhibit muzzle rise when fired. Ingram added a small bracket with a small strap beneath the muzzle to aid in controlling recoil during fully automatic fire. The original rate of fire for the M-10 in .45 is approximately 1090 rounds per minute. That of the M11/nine 9mm is approximately 1250 rounds per minute, and that of the M11 .380 is 1380 rounds per minute.

Suppressor

The primary reason for the original M-10 finding recognition was its revolutionary sound suppressor designed by Mitchell Werbell III of Sionics. This suppressor had a two-stage design, with the first stage being larger than the second. This uniquely shaped suppressor gave the MAC-10 a very distinctive look. It was also very quiet, to the point that the bolt could be heard cycling, along with the suppressed report of the weapon’s discharge; however, only if subsonic rounds were used. The suppressor when used with a Nomex cover created a place to hold the firearm with the secondary hand, making it easier to control. During the 1970s the United States placed restrictions on the exportation of suppressors, and a number of countries canceled their orders of M-10s as the effectiveness of the MAC-10’s suppressor was one of its main selling points. This was one factor that led to the bankruptcy of Military Armament Corporation, another being the company’s failure to recognize the private market. The original Sionics suppressor is 11.44 inches in length, 2.13 inches in overall diameter, and weighs 1.20 pounds.

Nomenclature

The term “MAC-10” is commonly used, but unofficial, parlance. Military Armament Corporation never used the nomenclature MAC-10 on any of its catalogs or sales literature, but because “MAC-10” became so frequently used by Title II dealers, gun writers, and collectors, it is used more frequently than “M10” to identify the gun.

Calibers and Variants

While the original M-10 was available chambered for either .45 ACP or 9mm, the M-10 is part of a series of machine pistols, the others being: the MAC-11 / M-11A1 semi, which is a scaled down version of the M-10 chambered in .380 ACP; and the M-11/9, which is a modified version of the M-11 with a longer receiver chambered in 9mm, later made by SWD (Sylvia and Wayne Daniel), Leinad and Vulcan Armament.

In the United States, machine guns are National Firearms Act items. As Military Armament Corporation was in bankruptcy large number of incomplete sheet metal frame flats were given serial numbers then bought by a new company, RPB industries. Some of the previously completed guns (already stamped MAC), were stamped on the other side RPB, making a “double stamp” gun.

RPB Industries made many open-bolt semi-automatic and sub-machine guns before the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (abbreviated ATF) seized roughly 200 open bolt semi autos during the drug wars of 1981. ATF insisted that all future semiautomatic versions were to be manufactured with a closed-bolt design as the open-bolt semiautomatics were considered too easy to illegally convert to full automatic operation.

Wayne Daniel, a former RPB machine operator, purchased much of their remaining inventory and formed SWD, designing a new weapon which was more balanced, available either fully or semi-automatic with his new ATF approved closed bolt design.

There are several carbine versions of the M-11/9 and Cobray and SWD manufactured a smaller version chambered in .380 ACP as a semiautomatic pistol called the M-12.

Today, while the civilian manufacture, sale and possession of post 1986 select-fire MAC-10 and variants is prohibited it is still legal to sell templates, tooling and manuals to complete such conversion. These items are typically marketed as being “post-sample” materials for use by Federal Firearm Licensees for manufacturing/distributing select-fire variants of the MAC-10 to Law Enforcement, Military and Overseas customers.

The Sass

Kukri

The kukri is a Nepalese knife with an inwardly curved blade, similar to a machete, used as both a tool and as a weapon in Nepal and some neighbouring countries of South Asia. Traditionally it was, and in many cases still is, the basic utility knife of the Nepalese people. It is a characteristic weapon of the Nepalese Army, the Royal Gurkha Rifles, Assam Rifles, Assam Regiment of Indian Army and of all Gurkha regiments throughout the world, so much so that some English-speakers refer to the weapon as a “Gurkha blade” or “Gurkha knife”. The kukri often appears in Nepalese heraldry and is used in many traditional rituals such as wedding ceremonies.

Manufacture

The Kami and Biswakarma castes are the traditional inheritors of the art of kukri-making. Modern kukri blades are often forged from spring steel, sometimes collected from recycled truck suspension units. The tang of the blade usually extends all the way through to the end of the handle; the small portion of the tang that projects through the end of the handle is hammered flat to secure the blade. Kukri blades have a hard, tempered edge and a softer spine. This enables them to maintain a sharp edge, yet tolerate impacts.

Kukri handles, usually made from hardwood or buffalo horn, are often fastened with a kind of tree sap called laha (also known as “Himalayan epoxy”). With a wood or horn handle, the tang may be heated and burned into the handle to ensure a tight fit, since only the section of handle which touches the blade is burned away. In more modern kukri, handles of cast aluminium or brass are press-fitted to the tang; as the hot metal cools it shrinks and hardens, locking onto the blade. Some kukri (such as the ones made by contractors for the modern Indian Army), have a very wide tang with handle slabs fastened on by two or more rivets, commonly called a full tang (panawal) configuration.

Weaponry

The kukri is effective as a chopping and slashing weapon. Because the blade bends towards the opponent, the user need not angle the wrist while executing a chopping motion. Unlike a straight-edged sword, the center of mass combined with the angle of the blade allow the kukri to slice as it chops. The edge slides across the target’s surface while the center of mass maintains momentum as the blade moving through the target’s cross-section. This gives the kukri a penetrative force disproportional to its length. The design enables the user to inflict deep wounds and to penetrate bone.

At the base of the blade is a notch called the cho. In addition to the cho’s symbolic meaning, it serves to stop blood from reaching the handle, which could make it slippery while preparing meat or use in combat. (This is not the reason for the cho’s existence. The blood from the wound inflicted would not just run along the sharpened edge, but along the flat sides as well. It is more likely that the cho also creates a “stop” point for sharpening.) In India the kukri sometimes incorporates a Mughal-style hilt in the fashion of the talwar but the plainer traditional form is preferred in Nepal.

The Sass

Anthroposophy, a philosophy founded by Rudolf Steiner, postulates the existence of an objective, intellectually comprehensible spiritual world that is accessible by direct experience through inner development. More specifically, it aims to develop faculties of perceptive imagination, inspiration and intuition through the cultivation of a form of thinking independent of sensory experience, and to present the results thus derived in a manner subject to rational verification. Anthroposophy aims to attain in its study of spiritual experience the precision and clarity attained by the natural sciences in their investigations of the physical world. The philosophy has double roots in German idealism and German mysticism and was initially expressed in language drawn from Theosophy.

Anthroposophical ideas have been applied practically in many areas including Steiner/Waldorf education, special education (most prominently through the Camphill Movement), biodynamic agriculture, medicine, ethical banking, organizational development, and the arts. The Anthroposophical Society has its international center at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.

Modern analysts, including Michael Shermer, have termed anthroposophy’s application in areas such as medicine, biology and biodynamic agriculture pseudoscience.

History

The early work of the founder of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner, culminated in his Philosophy of Freedom (also translated as The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path). Here, Steiner developed a concept of free will based on inner experiences, especially those that occur in the creative activity of independent thought.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Steiner’s interests turned to explicitly spiritual areas of research. His work began to interest others interested in spiritual ideas; among these was the Theosophical Society. From 1900 on, thanks to the positive reception given to his ideas, Steiner focused increasingly on his work with the Theosophical Society becoming the secretary of its section in Germany in 1902. During the years of his leadership, membership increased dramatically, from a few individuals to sixty-nine Lodges.

By 1907, a split between Steiner and the mainstream Theosophical Society had begun to become apparent. While the Society was oriented toward an Eastern and especially Indian approach, Steiner was trying to develop a path that embraced Christianity and natural science. The split became irrevocable when Annie Besant, then president of the Theosophical Society, began to present the child Jiddu Krishnamurti as the reincarnated Christ. Steiner strongly objected and considered any comparison between Krishnamurti and Christ to be nonsense; many years later, Krishnamurti also repudiated the assertion. Steiner’s continuing differences with Besant led him to separate from the Theosophical Society Adyar; he was followed by the great majority of the membership of the Theosophical Society’s German Section, as well as members of other national sections.

By this time, Steiner had reached considerable stature as a spiritual teacher. He spoke about what he considered to be his direct experience of the Akashic Records (sometimes called the “Akasha Chronicle”), thought to be a spiritual chronicle of the history, pre-history, and future of the world and mankind. In a number of works, Steiner described a path of inner development he felt would let anyone attain comparable spiritual experiences. Sound vision could be developed, in part, by practicing rigorous forms of ethical and cognitive self-discipline, concentration, and meditation; in particular, a person’s moral development must precede the development of spiritual faculties.

Luc Paquin

Measurement of Outcomes (AA: MoO)

Purpose

In order to determine if speech-language therapy has positive effect, reliable measurement tools are required to document outcomes. Currently, there is very limited information concerning the measurement of changes in speech production as a result of treatment for acquired apraxia of speech and aphasia. This study will obtain information concerning the reliability of several speech production measures over time. Thirty persons with chronic aphasia and apraxia of speech will be asked to provide speech samples in response to commonly used assessment tools on three sampling occasions so that the stability of measurements may be examined.

After establishment of appropriate outcome measures, a small, pilot treatment study will be conducted with four participants. The participants will receive a new treatment for aphasia and acquired apraxia of speech and outcomes will be measured relative to speech and language production.

Detailed Description:

A single group, repeated measures design will be used to obtain repeated speech samples from 30 persons with chronic acquired apraxia of speech and aphasia. Speech samples will be elicited using commonly employed motor speech assessment protocols; an initial sample, a sample one week following the initial sample, and a sample at four weeks following the initial sample. The following measures will be obtained from the samples: percent consonants correct, percent fluent utterances, and duration of utterance. Stability of the measures will be examined.

After the preceding measures have been analyzed, a series of four, single-subject experimental designs will be conducted. Four participants with chronic aphasia and apraxia of speech will receive a new treatment for aphasia and apraxia of speech applied sequentially to two sets of experimental picture picture stimuli. Outcomes will be measured in terms of speech production (measures described above) as well as in terms of language production.

Criteria

Inclusion Criteria:

- Veterans or nonveterans with aphasia and apraxia of speech who reside in the Salt Lake City region (commutable),

- 12 months or more post stroke or other focal brain injury, no other neurological conditions,

- Native English speakers, hearing adequate for experimental task (e.g., pass puretone screening at 35dB at 500, 1K, 2K Hz),

- Non linguistic cognition within normal limits

Exclusion Criteria:

- Less than 12 months post stroke,

- Insufficient hearing, insufficient non linguistic cognitive skills,

- Neurological conditions other than stroke,

- More than one stroke or brain injury,

- Unable to attend treatment in the Salt Lake City vicinity

Contacts and Locations

Choosing to participate in a study is an important personal decision. Talk with your doctor and family members or friends about deciding to join a study. To learn more about this study, you or your doctor may contact the study research staff using the Contacts provided below.

Contact: Julie L Wambaugh, PhD

Norma

A spiritual practice or spiritual discipline (often including spiritual exercises) is the regular or full-time performance of actions and activities undertaken for the purpose of cultivating spiritual development. A common metaphor used in the spiritual traditions of the world’s great religions is that of walking a path. Therefore a spiritual practice moves a person along a path towards a goal. The goal is variously referred to as salvation, liberation or union (with God). A person who walks such a path is sometimes referred to as a wayfarer or a pilgrim.

Anthroposophy

Rudolf Steiner gave an extensive set of exercises for spiritual development. Some of these were intended for general use, while others were for certain professions, including teachers, doctors, and priests, or were given to private individuals.

Martial Arts

Some martial arts, like T’ai chi ch’uan, Aikido, and Jujutsu, are considered spiritual practices by some of their practitioners.

New Age

Passage meditation was a practice recommended by Eknath Easwaran which involves the memorization and silent repetition of passages of scripture from the world’s religions.

Adidam (the name of both the religion and practice) taught by Adi Da Samraj uses an extensive group of spiritual practices including ceremonial invocation (puja) and body disciplines such as exercise, a modified yoga, dietary restrictions and bodily service. These are all rooted in a fundamental devotional practice of Guru bhakti based in self-understanding rather than conventional religious seeking.

The term Neotantra refers to a modern collection of practices and schools in the West that integrates the sacred with the sexual, and de-emphasizes the reliance on Gurus.

Recent and evolving spiritual practices in the West have also explored the integration of aboriginal instruments such as the Didgeridoo, extended chanting as in Kirtan, or other breathwork taken outside of the context of Eastern lineages or spiritual beliefs, such as Quantum Light Breath.

Stoicism

Stoicism takes the view that philosophy is not just a set of beliefs or ethical claims, it is a way of life and discourse involving constant practice and training (e.g., asceticism). Stoic spiritual practices and exercises include contemplation of death and other events that are typically thought negative, training attention to remain in the present moment (similar to some forms of Eastern meditation), daily reflection on everyday problems and possible solutions, keeping a personal journal, and so on. Philosophy for a Stoic is an active process of constant practice and self-reminder.

Luc Paquin

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets, which were used to write various Germanic languages before the adoption of the Latin alphabet and for specialised purposes thereafter. The Scandinavian variants are also known as futhark or fuþark (derived from their first six letters of the alphabet: F, U, Þ, A, R, and K); the Anglo-Saxon variant is futhorc or fuþorc (due to sound changes undergone in Old English by the names of those six letters).

Runology is the study of the runic alphabets, runic inscriptions, runestones, and their history. Runology forms a specialised branch of Germanic linguistics.

The earliest runic inscriptions date from around 150 AD. The characters were generally replaced by the Latin alphabet as the cultures that had used runes underwent Christianisation, by approximately 700 AD in central Europe and 1100 AD in northern Europe. However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes in northern Europe. Until the early 20th century, runes were used in rural Sweden for decorative purposes in Dalarna and on Runic calendars.

The three best-known runic alphabets are the Elder Futhark (around 150-800 AD), the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc (400-1100 AD), and the Younger Futhark (800-1100 AD). The Younger Futhark is divided further into the long-branch runes (also called Danish, although they were also used in Norway and Sweden); short-branch or Rök runes (also called Swedish-Norwegian, although they were also used in Denmark); and the stavlösa or Hälsinge runes (staveless runes). The Younger Futhark developed further into the Marcomannic runes, the Medieval runes (1100-1500 AD), and the Dalecarlian runes (around 1500-1800 AD).

Runic Magic

There is some evidence that, in addition to being a writing system, runes historically served purposes of magic. This is the case from earliest epigraphic evidence of the Roman to Germanic Iron Age, with non-linguistic inscriptions and the alu word. An erilaz appears to have been a person versed in runes, including their magic applications.

In medieval sources, notably the Poetic Edda, the Sigrdrífumál mentions “victory runes” to be carved on a sword, “some on the grasp and some on the inlay, and name Tyr twice.”

In early modern and modern times, related folklore and superstition is recorded in the form of the Icelandic magical staves. In the early 20th century, Germanic mysticism coins new forms of “runic magic”, some of which were continued or developed further by contemporary adherents of Germanic Neopaganism. Modern systems of runic divination are based on Hermeticism, classical Occultism, and the I Ching.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

The term “spiritual” is now frequently used in contexts in which the term “religious” was formerly employed. Contemporary spirituality is also called “post-traditional spirituality” and “New Age spirituality”. Hanegraaf makes a distinction between two “New Age” movements: New Age in a restricted sense, which originated primarily in mid-twentieth century England and had its roots in Theosophy and Anthroposophy, and “New Age in a general sense, which emerged in the later 1970s

- …when increasing numbers of people […] began to perceive a broad similarity between a wide variety of “alternative ideas” and pursuits, and started to think of them as part of one “movement”.

Those who speak of spirituality outside of religion often define themselves as spiritual but not religious and generally believe in the existence of different “spiritual paths,” emphasizing the importance of finding one’s own individual path to spirituality. According to one 2005 poll, about 24% of the United States population identifies itself as spiritual but not religious.

Characteristics

Modern spirituality is centered on the “deepest values and meanings by which people live.” It embraces the idea of an ultimate or an alleged immaterial reality. It envisions an inner path enabling a person to discover the essence of his/her being.

Not all modern notions of spirituality embrace transcendental ideas. Secular spirituality emphasizes humanistic ideas on moral character (qualities such as love, compassion, patience, tolerance, forgiveness, contentment, responsibility, harmony, and a concern for others). These are aspects of life and human experience which go beyond a purely materialist view of the world without necessarily accepting belief in a supernatural reality or divine being. Nevertheless, many humanists (e.g. Bertrand Russell) who clearly value the non-material, communal and virtuous aspects of life reject this usage of the term spirituality as being overly-broad (i.e. it effectively amounts to saying “everything and anything that is good and virtuous is necessarily spiritual”) Similarly, Aristotle – one of first known Western thinkers to demonstrate that morality, virtue and goodness can be derived without appealing to supernatural forces – even argued that “men create Gods in their own image” (not the other way around).

Although personal well-being, both physical and psychological, is an important aspect of modern spirituality, this does not imply spirituality is essential to achieving happiness. Atheists and others who reject notions that the numinous/non-material is important to living well can be just as happy as more spiritually-oriented individuals.

Contemporary spirituality theorists assert that spirituality develops inner peace and forms a foundation for happiness. For example, Meditation and similar practices are suggested to help practitioners cultivate his or her inner life and character. Ellison and Fan (2008) assert that spirituality causes a wide array of positive health outcomes, including “morale, happiness, and life satisfaction.”. However, Schuurmans-Stekhoven (2013) actively attempted to replicate this research and found more “mixed” results. Spirituality has played a central role in self-help movements such as Alcoholics Anonymous:

- …if an alcoholic failed to perfect and enlarge his spiritual life through work and self-sacrifice for others, he could not survive the certain trials and low spots ahead….

Spiritual Experience

“Spiritual experience” plays a central role in modern spirituality. This notion has been popularised by both western and Asian authors.

William James popularized the use of the term “religious experience” in his The Varieties of Religious Experience. It has also influenced the understanding of mysticism as a distinctive experience which supplies knowledge.

Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of “religious experience” further back to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of “religious experience” was used by Schleiermacher to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique. It was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential.

Major Asian influences were Vivekananda and D.T. Suzuki. Swami Vivekananda popularised a modern syncretitistic Hinduism, in which the authority of the scriptures was replaced by an emphasis on personal experience. D.T. Suzuki had a major influence on the popularisation of Zen in the west and popularized the idea of enlightenment as insight into a timeless, transcendent reality. Another example can be seen in Paul Brunton’s A Search in Secret India, which introduced Ramana Maharshi and Meher Baba to a western audience.

Spiritual experiences can include being connected to a larger reality, yielding a more comprehensive self; joining with other individuals or the human community; with nature or the cosmos; or with the divine realm.

Spiritual Practices

Waaijman discerns four forms of spiritual practices:

- Somatic practices, especially deprivation and diminishment. The deprivation purifies the body. Diminishment concerns the repulsement of ego-oriented impulses. Examples are fasting and poverty.

- Psychological practices, for example meditation.

- Social practices. Examples are the practice of obedience and communal ownership reform ego-orientedness into other-orientedness.

- Spiritual. All practices aim at purifying the ego-centeredness, and direct the abilities at the divine reality.

Spiritual practices may include meditation, mindfulness, prayer, the contemplation of sacred texts, ethical development, and the use of psychoactive substances (entheogens). Love and/or compassion are often described as the mainstay of spiritual development.

Within spirituality is also found “a common emphasis on the value of thoughtfulness, tolerance for breadth and practices and beliefs, and appreciation for the insights of other religious communities, as well as other sources of authority within the social sciences.”

Luc Paquin

Communication Strategies: Some Do and Don’t

The impact of aphasia on relationships may be profound, or only slight. No two people with aphasia are alike with respect to severity, former speech and language skills, or personality. But in all cases it is essential for the person to communicate as successfully as possible from the very beginning of the recovery process. Here are some suggestions to help communicate with a person with aphasia:

- Make sure you have the person’s attention before you start.

- Minimize or eliminate background noise (TV, radio, other people).

- Keep your own voice at a normal level, unless the person has indicated otherwise.

- Keep communication simple, but adult. Simplify your own sentence structure and reduce your rate of speech. Emphasize key words. Don’t “talk down” to the person with aphasia.

- Give them time to speak. Resist the urge to finish sentences or offer words.

- Communicate with drawings, gestures, writing and facial expressions in addition to speech.

- Confirm that you are communicating successfully with “yes” and “no” questions.

- Praise all attempts to speak and downplay any errors. Avoid insisting that that each word be produced perfectly.

- Engage in normal activities whenever possible. Do not shield people with aphasia from family or ignore them in a group conversation. Rather, try to involve them in family decision-making as much as possible. Keep them informed of events but avoid burdening them with day to day details.

- Encourage independence and avoid being overprotective.

Norma

“Spiritual but not religious”

“Spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) is a popular phrase and initialism used to self-identify a life stance of spirituality that rejects traditional organized religion as the sole or most valuable means of furthering spiritual growth.

The term is used world-wide, but is most prominent in the United States where one study reports that as many as 33% of people identify as spiritual but not religious. Other surveys report lower percentages ranging from 24% to 10%. The term has been called cliché by popular religious writers such as Robert Wright, but is gaining in popularity. The SBNR lifestyle is most studied in the population of the United States.

Definition

SBNR is commonly used to describe the demographic also known as unchurched, none of the above, more spiritual than religious, spiritually eclectic, unaffiliated, freethinkers, or spiritual seekers.

In 2013, Rabbi Rami Shapiro introduced the phrase “Spiritually Independent” as a new term to replace “SBNR” with a more positive statement which looks to the “politically independent” as a role model. Younger people are more likely to identify as SBNR than older people. In April 2010, the front page of USA Today claimed that 72% percent of Generation Y agree they are “more spiritual than religious”.

Those who identify as SBNR vary in their individual spiritual philosophies and practices and theological references, referencing some higher power or transcendent nature of reality, without belonging to a religious affiliation. In the USA most SBNR people without a religious affiliation believe in God.

Religion and Spirituality

Historically, the words religious and spiritual have been used synonymously to describe all the various aspects of the concept of religion. Gradually, the word spiritual came to be associated with the private realm of thought and experience while the word religious came to be connected with the public realm of membership in a religious institution with official denominational doctrines. Zinnbauer and Pargament (2005) write that in the early 1900s psychology scholars such as William James, Edwin Starbuck, G. Stanley Hall, and George Coe investigated religiosity and spirituality through a lens of social science.

- Books such as Robert C. Fuller’s Spiritual but not Religious: Understanding Unchurched America and Sven E. Erlandson’s Spiritual But Not Religious: A Call To Religious Revolution In America highlight the emerging usage of the term.

- In January 2012, Jefferson Bethke furthered the SBNR movement among evangelical Christians with his YouTube film “Why I Hate Religion, But Love Jesus,” in which he criticized organized religion as superficial and hypocritical. More traditionalist Evangelicals have countered that it is possible to have a spiritual relationship with God and follow organized religion. Some have argued that discarding religion is dangerous in that it removes the needed standards of doctrine and the Bible, which they claim are the avenue to true spirituality.

In the field of psychology, spirituality has emerged as a distinct social construct and focus of research since the 1980s. With the emergence of spirituality as a distinct concept from religion in both academic circles and common language, a tension has arisen between the two constructs. One possible differentiation among the three constructs religion, religiosity, and spirituality, is to view religion as primarily a social phenomenon while understanding spirituality on an individual level. Religiosity is generally viewed as being rooted in religion, whereas this is not necessarily the case for spirituality. A study of the differences between those self-identified as spiritual and those self-identified as religious found that the former have a loving, forgiving, and nonjudgmental view of the numinous, while those identifying themselves as religious see their god as more judgmental. Among other factors, declining membership of organized religions and the growth of secularism in the western world have given rise to this broader view of spirituality. The term “spiritual” is now frequently used in contexts in which the term “religious” was formerly employed. Both theistic and atheistic camps have criticized this development.

Luc Paquin