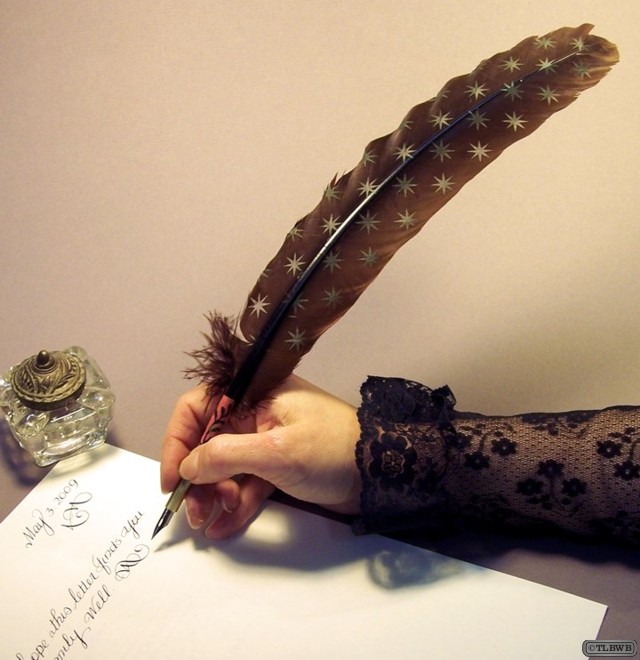

A quill pen is a writing implement made from a moulted flight feather (preferably a primary wing-feather) of a large bird. Quills were used for writing with ink before the invention of the dip pen, the metal-nibbed pen, the fountain pen, and, eventually, the ballpoint pen. The hand-cut goose quill is rarely used as a calligraphy tool, because many papers are now derived from wood pulp and wear down the quill very quickly. However, it is still the tool of choice for a few professionals and provides an unmatched sharp stroke as well as greater flexibility than a steel pen.

In a carefully prepared quill the slit does not widen through wetting and drying with ink. It will retain its shape adequately and only requires infrequent sharpening and can be used time and time again until there is little left of it. The hollow shaft of the feather (the calamus) acts as an ink reservoir and ink flows to the tip by capillary action.

The strongest quills come from the primary flight feathers discarded by birds during their annual moult. Generally the left wing (it is supposed) is favored by the right-handed majority of writers because the feather curves away from the sight line, over the back of the hand. This is actually urban myth. The quill barrel is cut to six or seven inches in length, so no such consideration of curvature or ‘sight-line’ is necessary. Additionally, writing with the left-hand in the long era of the quill was discouraged, and quills were never sold as left and right-handed, only by their size and species.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Modern Spirituality

Transcendentalism and Unitarian Universalism

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was a pioneer of the idea of spirituality as a distinct field. He was one of the major figures in Transcendentalism, an early 19th-century liberal Protestant movement, which was rooted in English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume. The Transcendentalists emphasised an intuitive, experiential approach of religion. Following Schleiermacher, an individual’s intuition of truth was taken as the criterion for truth. In the late 18th and early 19th century, the first translations of Hindu texts appeared, which were also read by the Transcendentalists, and influenced their thinking. They also endorsed universalist and Unitarianist ideas, leading to Unitarian Universalism, the idea that there must be truth in other religions as well, since a loving God would redeem all living beings, not just Christians.

Neo-Vedanta

An important influence on western spirituality was Neo-Vedanta, also called neo-Hinduism and Hindu Universalism, a modern interpretation of Hinduism which developed in response to western colonialism and orientalism. It aims to present Hinduism as a “homogenized ideal of Hinduism” with Advaita Vedanta as its central doctrine. Due to the colonisation of Asia by the western world, since the 19th century an exchange of ideas has been taking place between the western world and Asia, which also influenced western religiosity. Unitarianism, and the idea of Universalism, was brought to India by missionaries, and had a major influence on neo-Hinduism via Ram Mohan Roy’s Brahmo Samaj and Brahmoism. Roy attempted to modernise and reform Hinduism, from the idea of Universalism. This universalism was further popularised, and brought back to the west as neo-Vedanta, by Swami Vivekananda.

Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and the Perennial Philosophy

Another major influence on modern spirituality was the Theosophical Society, which searched for ‘secret teachings’ in Asian religions. It has been influential on modernist streams in several Asian religions, notably Neo-Vedanta, the revival of Theravada Buddhism, and Buddhist modernism, which have taken over modern western notions of personal experience and universalism and integrated them in their religious concepts. A second, related influence was Anthroposophy, whose founder, Rudolf Steiner, was particularly interested in developing a genuine Western spirituality, and in the ways that such a spirituality could transform practical institutions such as education, agriculture, and medicine.

The influence of Asian traditions on western modern spirituality was also furthered by the Perennial Philosophy, whose main proponent Aldous Huxley was deeply influenced by Vivekanda’s Neo-Vedanta and Universalism, and the spread of social welfare, education and mass travel after World War Two.

Important early 20th century western writers who studied the phenomenon of spirituality, and their works, include William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), and Rudolph Otto, especially The Idea of the Holy (1917). James’ notions of “spiritual experience” had a further influence on the modernist streams in Asian traditions, making them even further recognisable for a western audience.

“Spiritual but not religious”

After the Second World War spirituality and religion became disconnected, and spirituality became more oriented on subjective experience, instead of “attempts to place the self within a broader ontological context.” A new discourse developed, in which (humanistic) psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions are being blended, to reach the true self by self-disclosure, free expression and meditation.

The distinction between the spiritual and the religious became more common in the popular mind during the late 20th century with the rise of secularism and the advent of the New Age movement. Authors such as Chris Griscom and Shirley MacLaine explored it in numerous ways in their books. Paul Heelas noted the development within New Age circles of what he called “seminar spirituality”: structured offerings complementing consumer choice with spiritual options.

Among other factors, declining membership of organized religions and the growth of secularism in the western world have given rise to this broader view of spirituality. The term “spiritual” is now frequently used in contexts in which the term “religious” was formerly employed. Both theists and atheists have criticized this development.

Luc Paquin

Some people with aphasia may have trouble thinking of the word that they want to write, even though they know the meaning or message that they want to communicate. In this case, the person will not be able to write the word or say it, because they cannot think of the word itself. We have all experienced this kind of problem, often called “tip of the tongue”. You know the name of a person, place, or object, you can picture it clearly, you can describe it, but you just can’t think of the name of it. When this happens to you, you can neither say the word nor write it.

In other cases, the person with aphasia may know the word that they would like to write, and they might be able to say it, but they can’t write it. In this case, the sounds that need to be put together to say the word are accessible, but the spelling of the word is not. This may seem odd to those of us without aphasia. Our abilities to pronounce words and write them are so closely intertwined that it is hard for us to imagine being able to do one but not the other. But that is what can happen in aphasia.

Sometimes certain kinds of information about the word is available. Sometimes a related word might end up being written, for example, writing “apple” when you want to write “banana”. Other times the person with aphasia might be able to write the first letter, or draw slots for how many letters are in the word, or write the first and last letters, but make mistakes on the remaining letters. In this case, preserved information about what the written word looks like is there, but it’s not complete.

Some people with aphasia might write extra letters or words, or even write down non-words.

Finally, some people who have a nonfluent type of aphasia might be able to write some words but omit “little” words or have more trouble with verbs. They will have more trouble writing sentences.

Norma

Classical, medieval and early modern periods

Words translatable as ‘spirituality’ first began to arise in the 5th century and only entered common use toward the end of the Middle Ages. In a Biblical context the term means being animated by God, to be driven by the Holy Spirit, as opposed to a life which rejects this influence.

In the 11th century this meaning changed. Spirituality began to denote the mental aspect of life, as opposed to the material and sensual aspects of life, “the ecclesiastical sphere of light against the dark world of matter”. In the 13th century “spirituality” acquired a social and psychological meaning. Socially it denoted the territory of the clergy: “The ecclesiastical against the temporary possessions, the ecclesiastical against the secular authority, the clerical class against the secular class”. Psychologically, it denoted the realm of the inner life: “The purity of motives, affections, intentions, inner dispositions, the psychology of the spiritual life, the analysis of the feelings”.

In the 17th and 18th century a distinction was made between higher and lower forms of spirituality: “A spiritual man is one who is Christian ‘more abundantly and deeper than others’.” The word was also associated with mysticism and quietism, and acquired a negative meaning.

Luc Paquin

This calligraphy parchment paper has a fine surface texture that is excellent with inks. Specially designed for calligraphic projects. Parchment paper is ideal for invitations, certificates, stationery and student artwork. This collection of parchment-toned paper includes dozens of sheets in assorted tints, each with a smooth surface for even, fluid ink flow.

More durable than ordinary paper and imbued with a pale cream color, this heavy parchment pack is perfect for the rigors of spellcraft.

Use it in Journals if your pages are wearing out or you need to add some pages to it!!!

Write spells or Sabbats Recipes. This is Heavy Good Quality Parchment Paper.

Magical Uses:

This parchment can be used for many things including, creating your own spell work, spell magic for rituals to placed in your BOS, Book of shadows, for ceremonies & incantations & Scrolls. Also can be used a journal or diary pages.

This is True spell parchment not just colored paper or thick vellum board.

The Lost Bearded White Brother

Make the Connection

Taking the path less traveled by exploring your spirituality can lead to a clearer life purpose, better personal relationships and enhanced stress management skills.

Some stress relief tools are very tangible: exercising more, eating healthy foods and talking with friends. A less tangible – but no less useful – way to find stress relief is through spirituality.

What is Spirituality?

Spirituality has many definitions, but at its core spirituality helps to give our lives context. It’s not necessarily connected to a specific belief system or even religious worship. Instead, it arises from your connection with yourself and with others, the development of your personal value system, and your search for meaning in life.

For many, spirituality takes the form of religious observance, prayer, meditation or a belief in a higher power. For others, it can be found in nature, music, art or a secular community. Spirituality is different for everyone.

How can spirituality help with stress relief?

Spirituality has many benefits for stress relief and overall mental health. It can help you:

- Feel a sense of purpose. Cultivating your spirituality may help uncover what’s most meaningful in your life. By clarifying what’s most important, you can focus less on the unimportant things and eliminate stress.

- Connect to the world. The more you feel you have a purpose in the world, the less solitary you feel – even when you’re alone. This can lead to a valuable inner peace during difficult times.

- Release control. When you feel part of a greater whole, you realize that you aren’t responsible for everything that happens in life. You can share the burden of tough times as well as the joys of life’s blessings with those around you.

- Expand your support network. Whether you find spirituality in a church, mosque or synagogue, in your family, or in nature walks with a friend, this sharing of spiritual expression can help build relationships.

- Lead a healthier life. People who consider themselves spiritual appear to be better able to cope with stress and heal from illness or addiction faster.

Discovering your Spirituality

Uncovering your spirituality may take some self-discovery. Here are some questions to ask yourself to discover what experiences and values define you:

- What are your important relationships?

- What do you value most in your life?

- What people give you a sense of community?

- What inspires you and gives you hope?

- What brings you joy?

- What are your proudest achievements?

The answers to such questions help you identify the most important people and experiences in your life. With this information, you can focus your search for spirituality on the relationships and activities in life that have helped define you as a person and those that continue to inspire your personal growth.

Luc Paquin

Some people with aphasia have difficulty processing the written words that they see.

It is possible for a person with aphasia to look at one word, for example, “fork”, and think of a spoon or something else related to “fork”. Another kind of problem is to look at a written word and fail to recognize it in any meaningful way. For example, a person with aphasia could look at a written word like “fork” and not be able to think what it means. In these cases, it is helpful to add additional written information, gesture, or pictures, to help reading comprehension. Compare the following two statements: “Get the spoon” and “Get the spoon – the one for soup”. In the second statement there is additional information that may help trigger the correct meaning of the target, “spoon”. Even though the second statement is longer, it provides redundancy which helps comprehension.

Some people with aphasia have trouble recognizing the letters. Letters may look like strange squiggles; the individual letters themselves may have lost their connection to meaning. Again, additional information provided either through writing, gesture, speech, or pictures, can help the person understand the written word.

Other types of aphasia affect reading comprehension because verb forms and small “functor” words like prepositions and articles have lost their meaning. In this case, a person with aphasia would have more trouble understanding a sentence that is longer and more complex than a simpler sentence.

It is important to note that silent reading comprehension is different than being able to read out loud. Many people with aphasia can understand written words and sentences but be unable to read them out loud. We are used to teaching children to read by hearing them read out loud, and estimating their ability to read through how well they can do so. This is not the same in adults with aphasia who were able to read prior to their stroke or brain injury. It is important to test these two skills – silent reading comprehension and reading out loud – separately.

Norma

Smith & Wesson Boot Knife

Smith & Wesson Boot Knife with Stainless Steel Blade 4 7/8″ 440C fixed blade, double edged boot knife. Handle made of stainless steel. 9 1/8″ overall length. Includes black leather boot sheath with pocket clip. Black rubberized handle with lanyard hole. Black leather belt/boot clip sheath.

- 4 7/8″ blade

- 9 1/8″ overall

- Stainless steel blade

- Brass

- U.S.A.

- Full tang black rubber handle

- Double edged spear point blade

- Comes with a black boot leather sheath

The Sass

Definition

There is no single, widely-agreed definition of spirituality. Surveys of the definition of the term, as used in scholarly research, show a broad range of definitions, with very limited similitude.

According to Waaijman, the traditional meaning of spirituality is a process of re-formation which “aims to recover the original shape of man, the image of God. To accomplish this, the re-formation is oriented at a mold, which represents the original shape: in Judaism the Torah, in Christianity Christ, in Buddhism Buddha, in the Islam Muhammad.”

In modern times the emphasis is on subjective experience. It may denote almost any kind of meaningful activity or blissful experience. It still denotes a process of transformation, but in a context separate from organized religious institutions, termed “spiritual but not religious”. Houtman and Aupers suggest that modern spirituality is a blend of humanistic psychology, mystical and esoteric traditions and eastern religions.

Waaijman points out that “spirituality” is only one term of a range of words which denote the praxis of spirituality. Some other terms are “Hasidism, contemplation, kabbala, asceticism, mysticism, perfection, devotion and piety”.

Etymology

The term spirit means “animating or vital principle in man and animals”. It is derived from the Old French espirit which comes from the Latin word spiritus (soul, courage, vigor, breath) and is related to spirare (to breathe). In the Vulgate the Latin word spiritus is used to translate the Greek pneuma and Hebrew ruah.

The term “spiritual”, matters “concerning the spirit”, is derived from Old French spirituel, which is derived from Latin spiritualis, which comes from spiritus or “spirit”.

The term “spirituality” is derived from Middle French spiritualité, from Late Latin “spiritualitatem” (nominative spiritualitas), which is also derived from Latin spiritualis.

Luc Paquin

A Wiccan altar is a “raised structure or place used for sacrifice, worship, or prayer”, upon which a Wiccan practitioner places several symbolic and functional items for the purpose of worshiping the God and Goddess, casting spells, and/or saying chants and prayers.

Altar Items

The altar is often considered a personal place where practitioners put their ritual items. Some practitioners may keep various religious items upon the altar, or they may use the altar and the items during their religious workings. According to Scott Cunningham, a popular Wiccan author, the left side of the altar should be considered the Goddess area; feminine or yonic symbols such as bowls and chalices, as well as Goddess representations and statues should be placed on the left. The right side is designated for the God; phallic symbols such as the athame and the wand are placed to the right side, as well as God statuary and his candle. The left and right associations vary according to personal preference, but the center area is almost always considered the “both” area, or the working area. In the center of the altar are kept the main symbols of the Wiccan faith, such as the pentacle.

Some Wiccans arrange their altars to represent all four elements and directions. In the North the earth element is represented; in the east is air, in the south is fire, and in the west water. These elements can be represented in various ways, but generally do not vary in elemental and directional correspondences. When placing items on an altar or when “calling on the elements” (a practice involving inviting the elements to be a part of the circle and lend their power) a practitioner will move deosil (clockwise or sunwise) and when dismissing the elements they will move widdershins (counter-clockwise).

Some of the items represent the Earth’s four elements, but elements may be represented more literally, with gems, salt, water, plant material, insect casings, etc.

Opening Of Circle

Walking clockwise from East.

By the air that is her breath

By the fire that is her bright spirit

By the living waters of her womb

And by the earth that is her body

The circle is cast,

Tie the knot of the circle

So Mote It Be!

Open The Circle

First cut the knot.

Walking counterclockwise from East.

By the air that is her breath

By the earth that is her body

By the living waters of her womb

And by the fire that is her bright spirit

The circle is open but not unbroken.

May the joy of the Goddess live in our hearts

Merry Meet,

Merry Part,

And Merry Meet Again!

The Lost Bearded White Brother